Stroom Invest interviews / artist Kim David Bots

Kim David Bots is working in residency at Het Pompgemaal in Den Helder. Far away from the restarting art scene, Bots tries to focus on new ideas, thoughts, dialogue and sounds. We speak with the help of a video connection about how things have developed up to this point.

Frits Dijcks: Three months of corona quarantine was not enough for you?

Kim David Bots: I wrote the application for this residency a year ago. But it is quite nice to be here. The corona lockdown period didn’t affect me that much. I just moved back and forth between my home and my studio. And in my normal life I only see a small group of people, that I continued seeing during the corona lockdown.

The corona virus did not change your plans for the residency?

I did a bit. I originally planned to do a series of presentations, but now I will focus more on the working process here. I think that is more relevant tight now, than showing work. In august I will invite people to work with me or to discuss the things I do. So it is a different way of sharing the residency. They are mostly people who I worked with before, and also have been meeting during the past months.

Born in Amsterdam, you studied in Utrecht. How did you end up in The Hague?

Two and a half years ago I was living in Brussels and I planned to go back to Amsterdam, but the rent for my living space there would double or even triple. So I panicked a bit. Then a friend artist from The Hague invited me to come to Billytown and do a three months residency in The Hague. After that I started hopping free studios spaces in Billytown and stayed there. I also found a bed at my sister’s house in The Hague. And now I am not interested in going back to Amsterdam anymore. The Hague has a lot to offer and there is a good art scene with a lot of diversity: young art initiatives, events and sound based arts. It’s a broad range of people. Quit amazing actually when you think of the village like character of the city. It is a good base and I can always do residencies and travel.

In Amsterdam this current idea of moving around all the time seems more like ‘precarity, sold as flexibility’ to me. You can tell yourself that your flexible, but you simply have no stable living and working situation. You don’t have time to do your work because you are concerned with earning money all the time. It becomes very hard to focus on your work, especially when you are young. I teach illustration at HKU in Utrecht. I finished the same art school just eight years ago and for me it was already so much easier than for the starting artists nowadays. But eight years is nothing. It’s insane that things change so rapidly. It is quite stressful.

You have a large interest in the trivial things in life. It pops up in all of your works. Where does that come from?

I always find it hard to formulate what my work does or what I am actually interested in. I am sort of dancing around subjects instead of pointing directly to them. I think triviality helps me to do this. This way I can indirectly discuss things without having the feeling of discussing them.

Is it avoidance? An aversion to use the big words?

Maybe it is. But I don’t feel this fringent distinction between the trivial and the important themes. When I work it doesn’t feel as a trivial thing to me. I can spent a lot of time doing trivial things feeling that it is really important. Afterwards I can see it is trivial or stupid. But it is an indirect way of dealing with things. I admire people who are able to use triviality to address larger subjects without mentioning them.

It is a method that artists use when they have to work in a situation of oppression.

I have an illustration background and I think illustration works in a similar way. On the surface it is really direct and basic core of communication. Stupid even. But it points at something important.

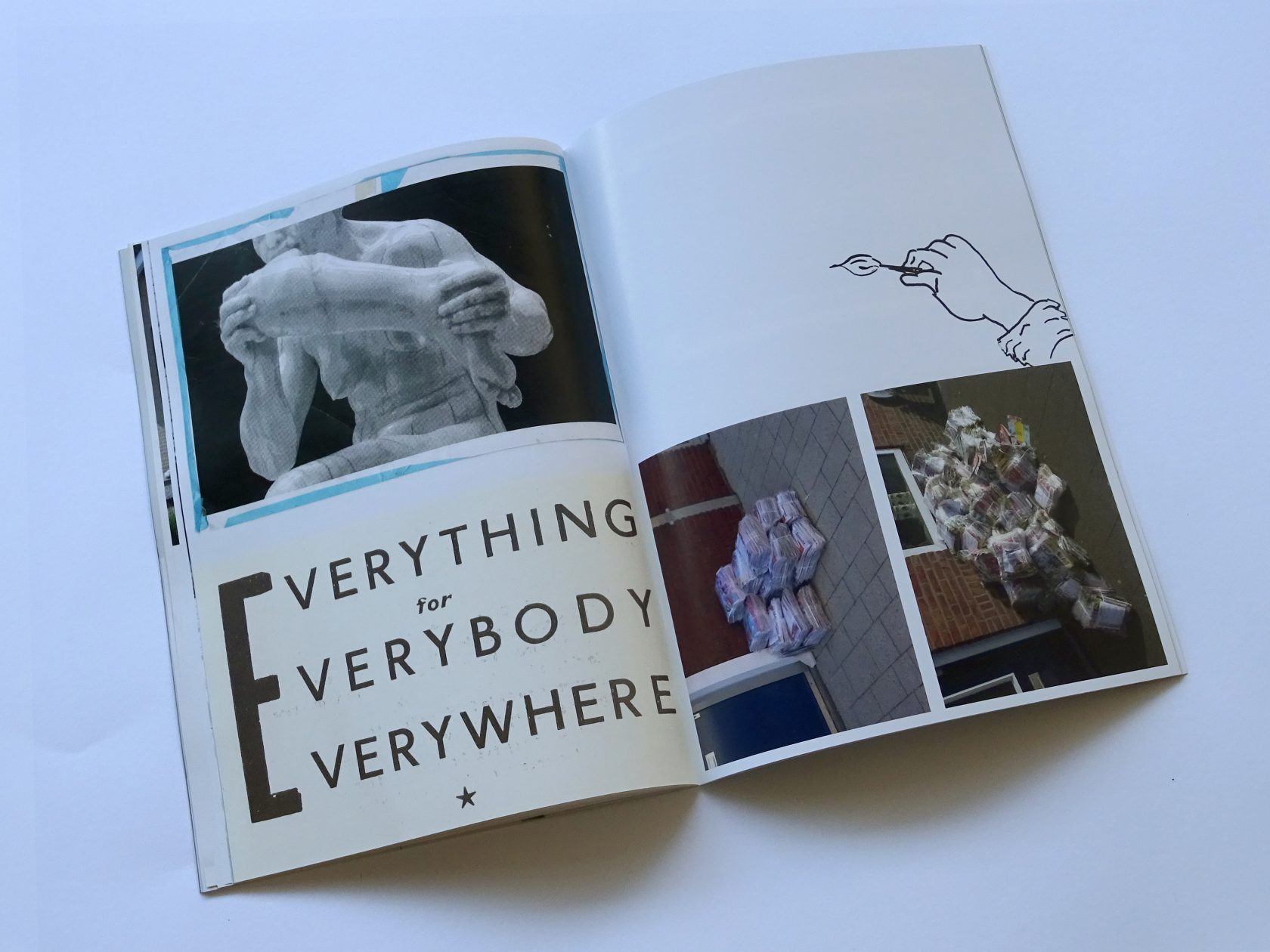

I recently collected a booklet made by the illustrator Jo Spier. You can buy it really cheap now. It was send to all Dutch households after WWII to explain the Marshall plan. It is very basic, but beautiful at the same time, which is why people have collected it. Looking back in time, you can see that it encapsulates the geopolitical situation in Europe and its relationship to America in a really simple way. And it also shows how debt played a role as a tool or political instrument. This simple booklet is trivial in its form but it also contains all these different ideas. Jo Spier was a jew who survived the concentration camps. After the war he got all sorts of assignments by the Dutch government as a kind of compensation.

I find it interesting that the things that seems trivial at first becomes interesting later on. The directness of the visual language makes you also receptive to the content.

You like a certain directness of language. Do you think art is the right field to work in? Art is very much context based. That makes it hard to be direct, don’t you think?

I like the directness of the language, but I don’t necessarily want to directly tell a story. I am fascinated by the idea that you can pretend to be direct and at the same time be fragmentarily vague. I agree that art is not the best environment to tell direct stories. Illustration is much better suited for this. Looking at the art works of others, I enjoy the ambiguity of it.

You made a change from illustration to art. And within fine art you also change between media a lot.

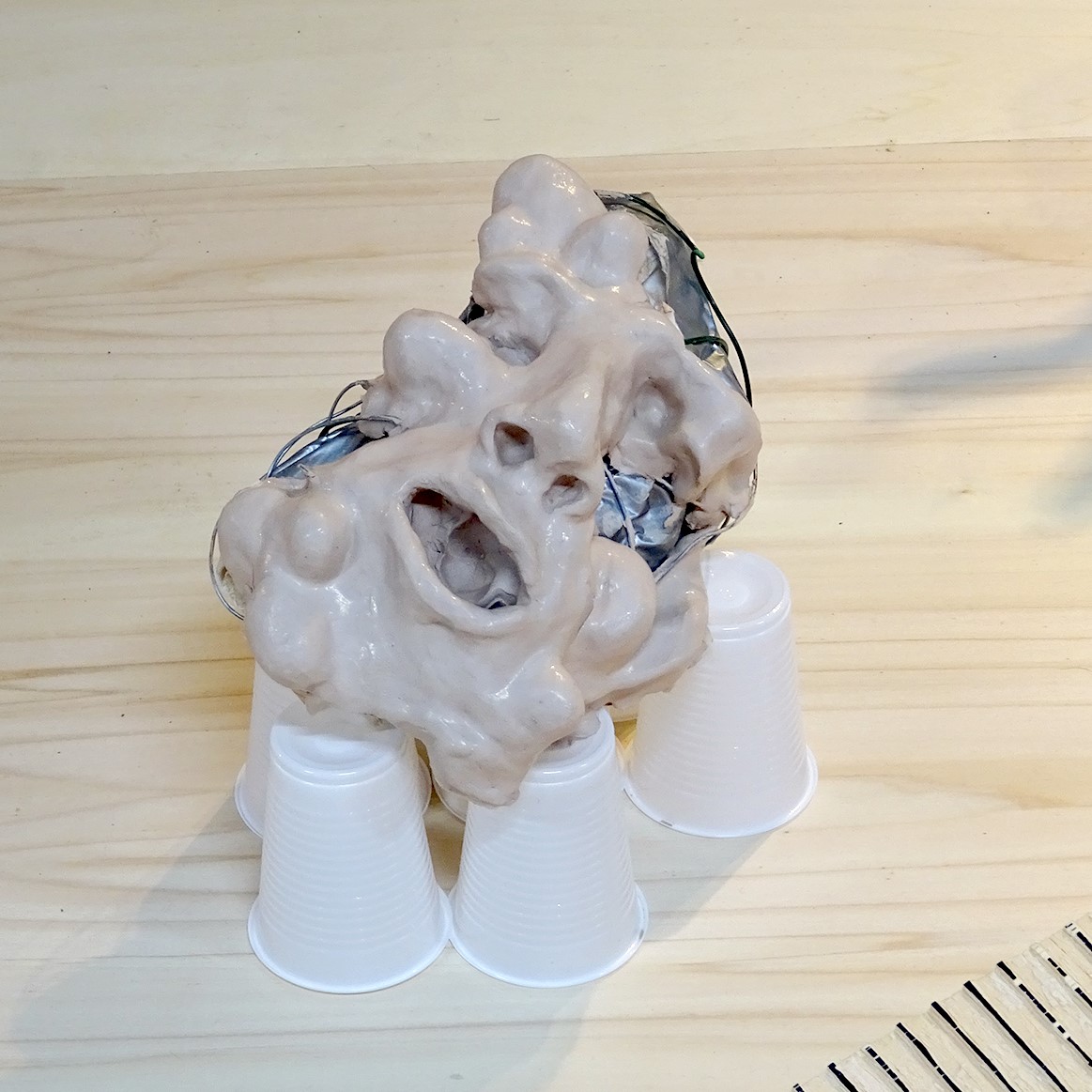

While studying illustration I already used audio and music. For me, they all are interrelated. It feels like changing media, but at the core is the idea that you use what you need to tell the story. So for me, it is not about experimenting with different media. Two years ago I had an exhibition at Kunstfort bij Vijfhuizen, an old bunker complex that was part of the defense line around Amsterdam. It was totally unsuitable for paintings and drawings. This was a good reason to do something else, so I made sculptural installations. I would never call myself a sculptor, because the things I make are quite flimsy. Which I like, because they feel less like art objects, but more like tools or things you can use once or maybe multiple times, but then I have to repair or change things a bit.

How do your ideas develop? Do they come from working on the spot or do you have a starting idea or thread?

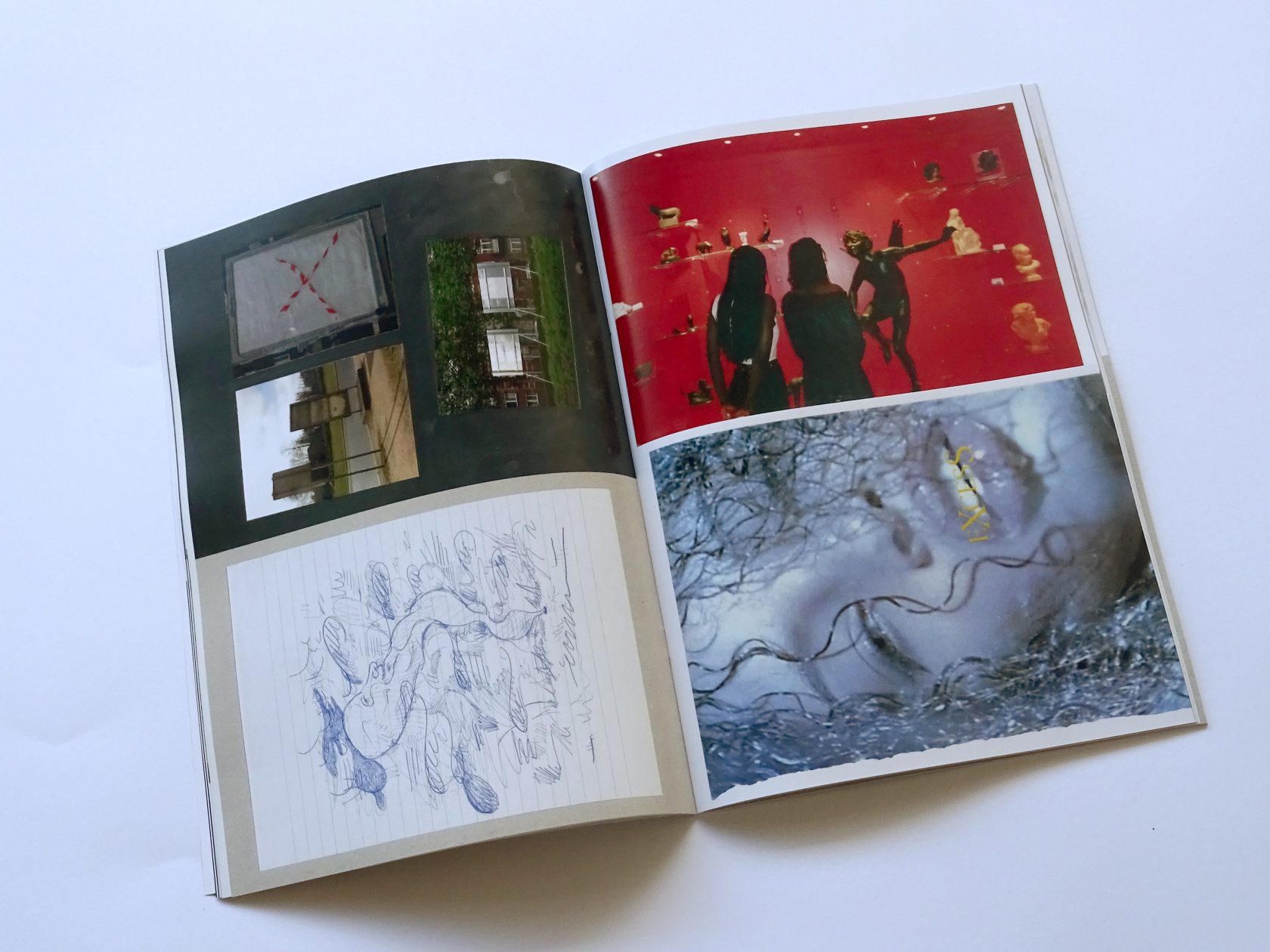

It really differs. I work from a sea of information. I collect stuff, that is a really important part of my practice. I am constantly collecting different, mostly trivial, things. I have no real starting point or finish line. I often think I am making notes for future projects, but they sometimes become works by themselves. But I also find it difficult to use the word ‘works’, because a lot of what I make is not that stable.

I read you tried to get rid of the narrative in your work. Or do you create narratives?

Where did you read that? I definitely think that I create narratives. I don’t have a story in mind and then make the stuff. But I think that I use a physical starting point in a painting, sculpture, a piece of audio or whatever. And the physical and narrative interchange and influence each other. You can’t read the story from the work. Or read the work from the story.

I also read that you like the construction of a good joke. That must be true, right?

Yes. Not only good jokes but also phrases that people use. They all have a similar value or feel to me, a bit like the Jo Spier booklet has. A saying or a good joke feels really direct, but there is also stuff underneath that slowly enters your brain. It is a bit like a ghost pepper. There is a direct heath, but also a heath that comes slowly after and really burns deeply. I like things that work that way.

Do you think a work of art can also work like that?

I enjoy the art that triggers an immediate response. And later when you are home you still have the lingering image in your mind. A feeling of still not understanding what you saw.

I saw a show in Brussels when I was doing a residency at WIELS. It was a show of one of my tutors. In a U-shaped space, the floor was covered with blue carpet. The right wall had realistic paintings of child benefit forms. An SM-hook at the ceiling. Around the corner a series of photographs of brick walls. And a loop of a YouTube download video of a British tv show called Rising Damp. The screened video was kind of skewed as if somebody bumped into the beamer. The audio of the video was removed and sounded at the entrance of the gallery space. When I saw the show, I was quite annoyed with it. I thought it pretended to say a lot and it felt quite demanding. But I went back later on, and then I really liked it.

I guess I was used to being annoyed be these kind of shows. I think this was my Pavlov response to a certain type of exhibitions. During the second visit the objects felt more interrelated. That was an interesting show for me, because before I trusted my first instinct more. Later I realized that all those works were kind of pluriform, just like the things I think about. I think that everything within an exhibition is true. There is no necessary truth to a work. Even when the maker of the work has a certain message or intention, all other views are just as true. This show kind of made that clear to me.

Was this also the start for you to work on spatial installations?

Yes. The exhibition at Kunstfort bij Vijfhuizen was three months later. It was uncomfortable at first. When I think back of the exhibition in Brussels, I don’t think it was a good exhibition, but it was a really helpful one for me.

Bad exhibitions can be more interesting than good ones.

Yes, indeed. And there always is this double purpose of exhibitions. You show your work to offer something to the viewer, but you offer something to yourself as well. So every exhibition is also a question to myself. I often work in situ. Some stuff is clearly a work on its own and others are sort of in between and unstable.

Do you interact with your audience during exhibitions?

I used not to do that, but lately I have the feeling that I should do that more. When you show a lot of stuff, it can be overwhelming. And people get the feeling that they should understand all of this and to read the meaning of every part of everything. And they start searching for meaning all the time.

Does this change your view on painting?

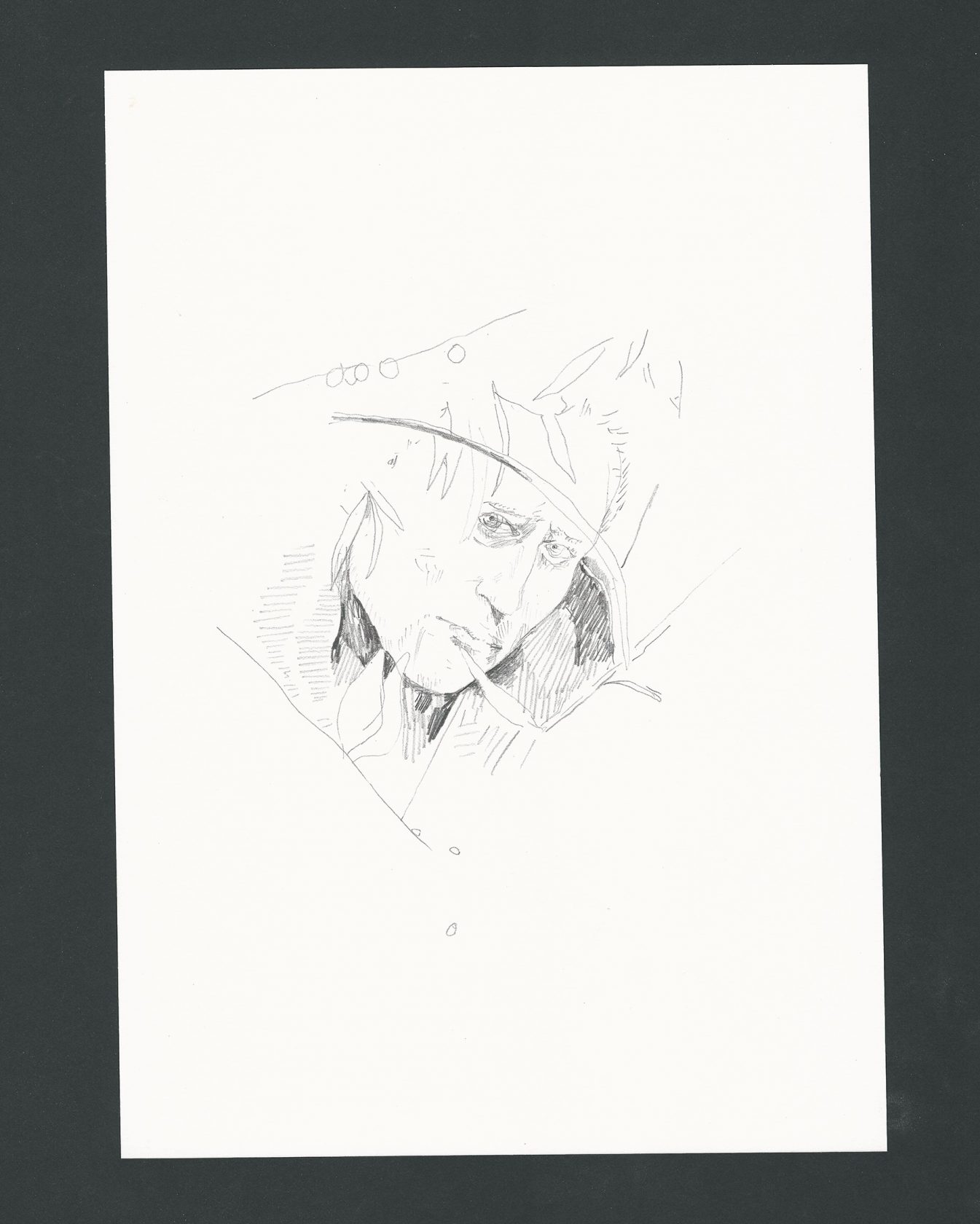

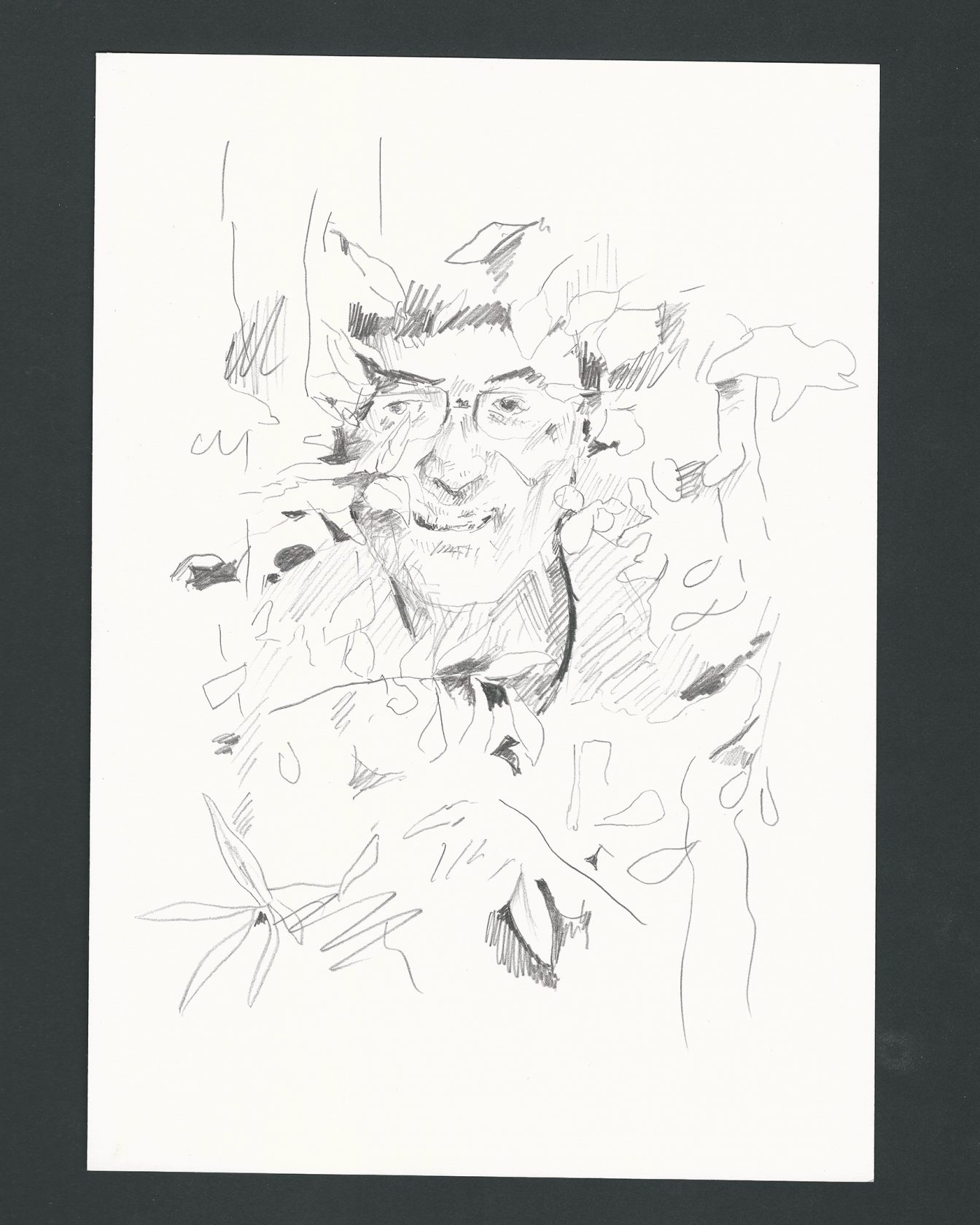

Painting feels like an elaborate way of note making. While painting, I am spending more time on one idea and I am trying to finish a thought. That is not the case in my installations, which is a collection of unfinished thoughts. That can also be annoying, I guess. Painting is a really good way to work out a thought into something definite. But I don’t know how to show paintings within an installation. It is an awkward feeling, that I like as well.

Maybe this comes close to the annoying experience in Brussels?

Yes, but it also forces you to formulate what their function is. Why does it feel awkward and why do I still feel the need to make them?

Drawing is a better way to connect different things?

Drawing is the first thing you do as a child. It is the thing you do before you start writing. It is really close to thinking.

Do you have any idea where you will be in about 5 years from now?

No. I also find that annoying sometimes. For this residency I bought an action camera. So now I am filming stuff. Which is also a problem for me and makes me think: do I really need another medium? It then feels like I am avoiding to get to a certain point within a medium. But I still am interested in telling stories. I made a small studio here with musical instruments and use my audio recorder to collect the sounds of this new environment. It is a different way of collecting. It can start a story in a totally different way. This month I will use to record and collect.

You also participated in the Stroom Invest program two years ago. What did you get from that?

All these studio visits are very helpful. They offer you a collection of voices that you can take with you in future thoughts. I still think about some remarks that Maziar Afrassiabi (Rib art space) made during the studio visit. He said something about knowing your own biography. To really know the people you are interested in. That still sticks in my head and pops up frequently. What do I like? I am still thinking about that.

Maybe you have a good joke for me to finish this interview with?

Ha, ha! Aaah, I am very bad at remembering and telling jokes. People usually fall asleep before I reach the punch line. I always forget the important stuff and add new things.

There are not much people who are able to tell a good joke. But maybe the results of this residency can be seen as a good joke.

I will try to fit in some good jokes.

The Invest Week is an annual 4-day program for artists who were granted the PRO Invest subsidy. This subsidy supports young artists based in The Hague in the development of their artistic practice and is aimed to keep artists and graduates of the art academy in the city of The Hague. In order to give the artists an extra incentive, Stroom organizes this week that consists of a public evening of talks, a program of studio visits, presentations and a number of informal meetings. The intent is to broaden the visibility of artists from The Hague through future exhibitions, presentations and exchange programs. The Invest Week 2020 will take place from 21 to 25 of September.