Making art with microorganisms / Interview with Ieva Maslinskaitė

Lithuanian artist Ieva Maslinskaitė had a year-long HIDE OUT residency at De Besturing, a creative work space in de Binckhorst in The Hague. She started working with microorganisms and got her Photography degree at the KABK last year. It opened her eyes. ‘We are actually more non-human than human.’

FEATURE | INTERVIEW

When did your interest in microbiology start?

I get this question a lot! I am not sure what the starting point was, but the first thing I was really interested in during my studies was the stigma surrounding bodily fluids and stains. I was learning about microorganisms, which kinds grows out from spit, your sweat, or when you touch something.

I did childish experiments that you learn at school and some tutorial-based research. That is when I understood how to connect it to more ecological inquiries that I have. How our bodies connect to more organisms than we can actually see. I learned it’s not necessarily a binary understanding of if being good, bad, harmful or beneficial.

What happened next?

I started doing research about emulsions and bacteria affecting each other. I struggled for a long time how to show this process. It made sense to me to have something that contains this process, because we are all contained in bodies and processes.

I had the idea glass could be interesting to work with, as it is fragile and see-through. I discovered this greenhouse glass I thought was very conceptually fitting material and I decided to use it. Glass is – just like the organisms – a vulnerable, fragile and uncontrollable material. The organisms might not work or cultivate or just die, and then the glass could break… I had a lot of stress while working with these fragile and alive materials, given their uncontrollable and vulnerable nature.

Going from photography to glass sculptures seems like a big step…

During the studies I was much more image-focused. I started to create more work that questions photography as a medium: who does it belong to, who can create their own representation when it comes to nature and environment? Sometimes I have to justify why I am not necessarily doing photography, but my work is always connected to the medium in some way.

I started using materials differently and thinking about the connotations they have. Greenhouse glass is the cheapest glass available. It is not about reusing glass as such, but about reusing glass from a greenhouse, where certain plant species are being owned or patented or reproduced.

For your glass sculptures you use an emulsion for blueprints. Can you explain how this works?

One of the first artists who did this was a botanist: Anna Atkins. Cyanotype was used by botanists to represent plant structures and to archive prints. It is an easy reusable process that became used for blueprints of buildings.

A cyanotype print is made of oxidised iron-based chemicals. It turns blue because of the sunlight. You wash out the chemicals and the blue stays.

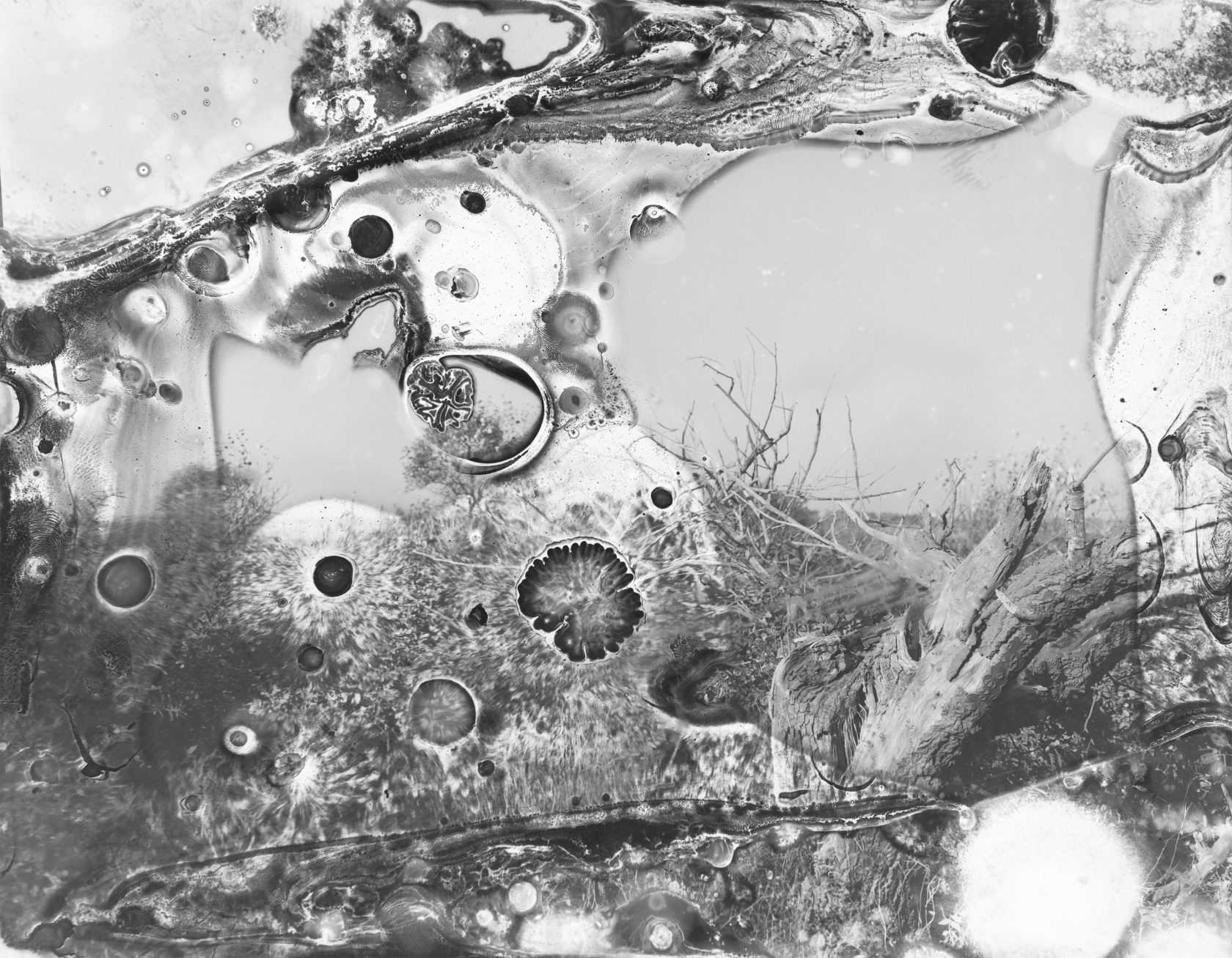

I used this emulsion to grow iron oxidising bacteria, a type of bacteria you find in riverbeds or next to rocks that have this copperish colour. In the water there’s a lot of iron that the bacteria oxidise. The image becomes more a place of living for natural processes, rather than a representation of nature.

And then you mix them together?

It’s light and time, and a specific medium based on agar, a plant-based gelatine that is used in both food and cultivating microorganisms. I mix this together with the cyanotype emulsion. The bacteria starts cultivating on that, because there’s iron and it grows. It sometimes starts growing mold when colonies are fighting with each other.

Then as time passes and because light is affecting this process in this glass, it starts getting to be more blue like the blueprint. The bacteria colonies spread and become this copperish mass. The agar starts drying out. At some point it’s like nothing but a little bio-plastic film that’s left.

How much time does it take?

It depends on the season and the temperature! In July it’s quite warm and because of that it evolves quickly. Within a week it’s already fully growing and disappearing as well.

In the winter it takes weeks. I was preparing for the graduation show when I suddenly realized had to work a lot faster to finish it on time… So temperature and light affect it a lot. In microbiology labs they have special boxes where it can grow faster, because they can regulate it much better.

The process is almost the artwork?

Definitely. My artwork does not really work without explanation. I personally love this feeling of understanding something through another perspective. That’s the best!

I am finding my own way of doing things and I am currently happy about it. However, it also causes frustrations, working with living processes. Sometimes I wish I have a simple print on the wall, it would be so much easier to show.

It is a paradoxical thing that I am trying to say things about control of our environment, but through making my work I am quite in control of other organisms. Then it becomes a dilemma: how far can I take this control? If one of my works is dying and disappearing, am I trying to force it to be something? Art is basically a human made concept. How can other organisms be creating it?

Your graduation work Unworlded, Bewildered is about ‘interspecies relations’. It sounds somewhat alien.

It is still funny to me there’s a distinction between the human and non-human. It is still more interconnected: there are more non-human cells than human cells in our body. In other words: we are more non-human than human if you would count it by cell.

Can a person emphasize with dying bacteria?

Maybe we can relate to other microorganisms more as part of our self, because we are full of microorganisms ourselves. It is more the question: am I able to take care of them and not feel like exploiting another species? If I try to keep them alive no matter what, that’s also me being in control, that’s not what I want to do…

I want bacteria to live their own life. But also… sometimes the bacteria are in control of me. Scientists have made new discoveries about gut and mind connections. Now we are drinking coffee and it’s interacting with the microbiota in our guts and influencing this conversation!

So I am not sure how much other organisms influence me through their existence… They make us get sick sometimes, or feel good if we have good bacteria from kefir. They have quite a big control over us and we are as vulnerable as they are.

Can microorganisms be in control in art as well?

I have done a workshop where we are trying to find out which organisms grow out of our body. Inside the Petri dishes our micro communities cultivate by themselves.

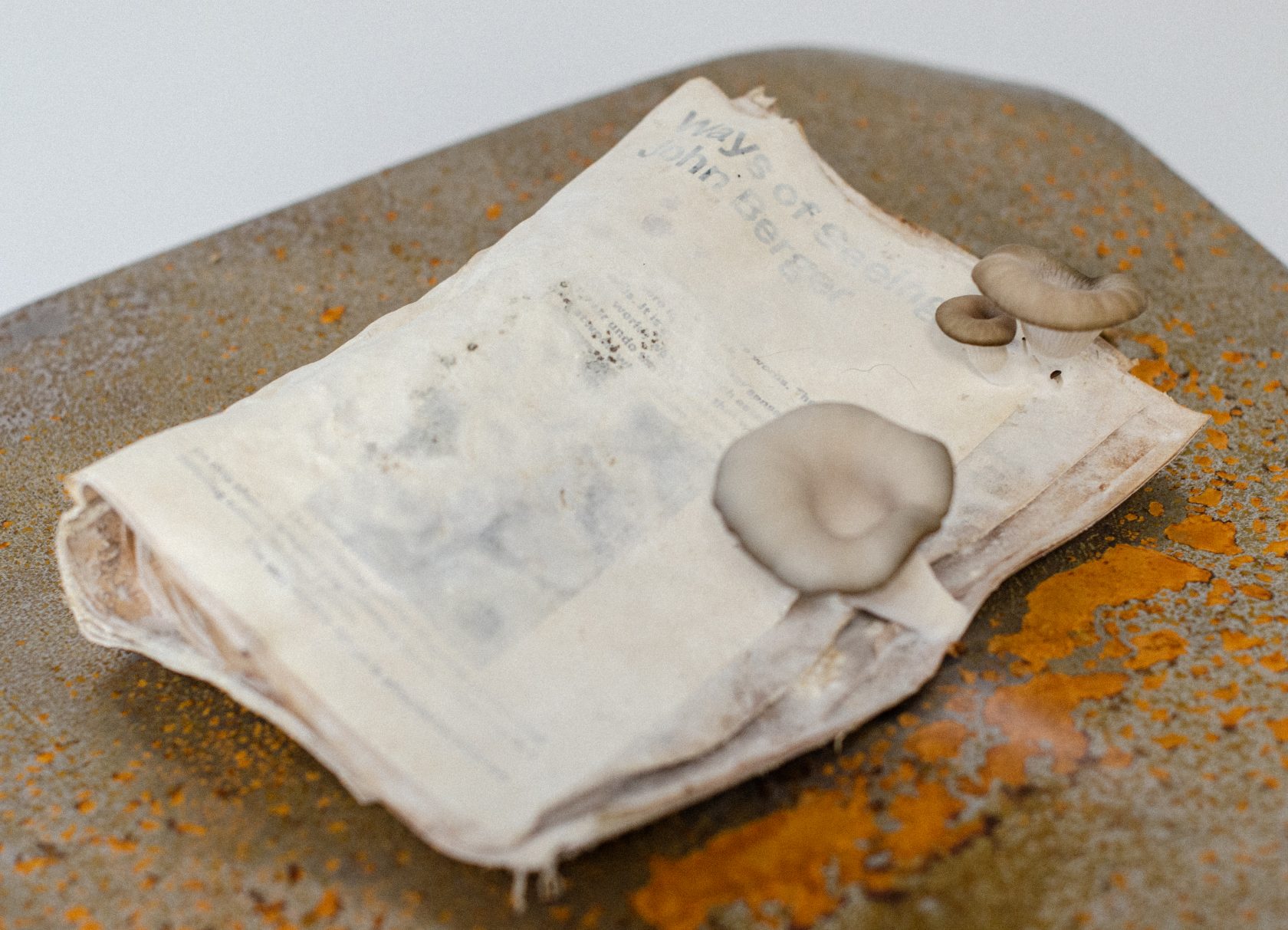

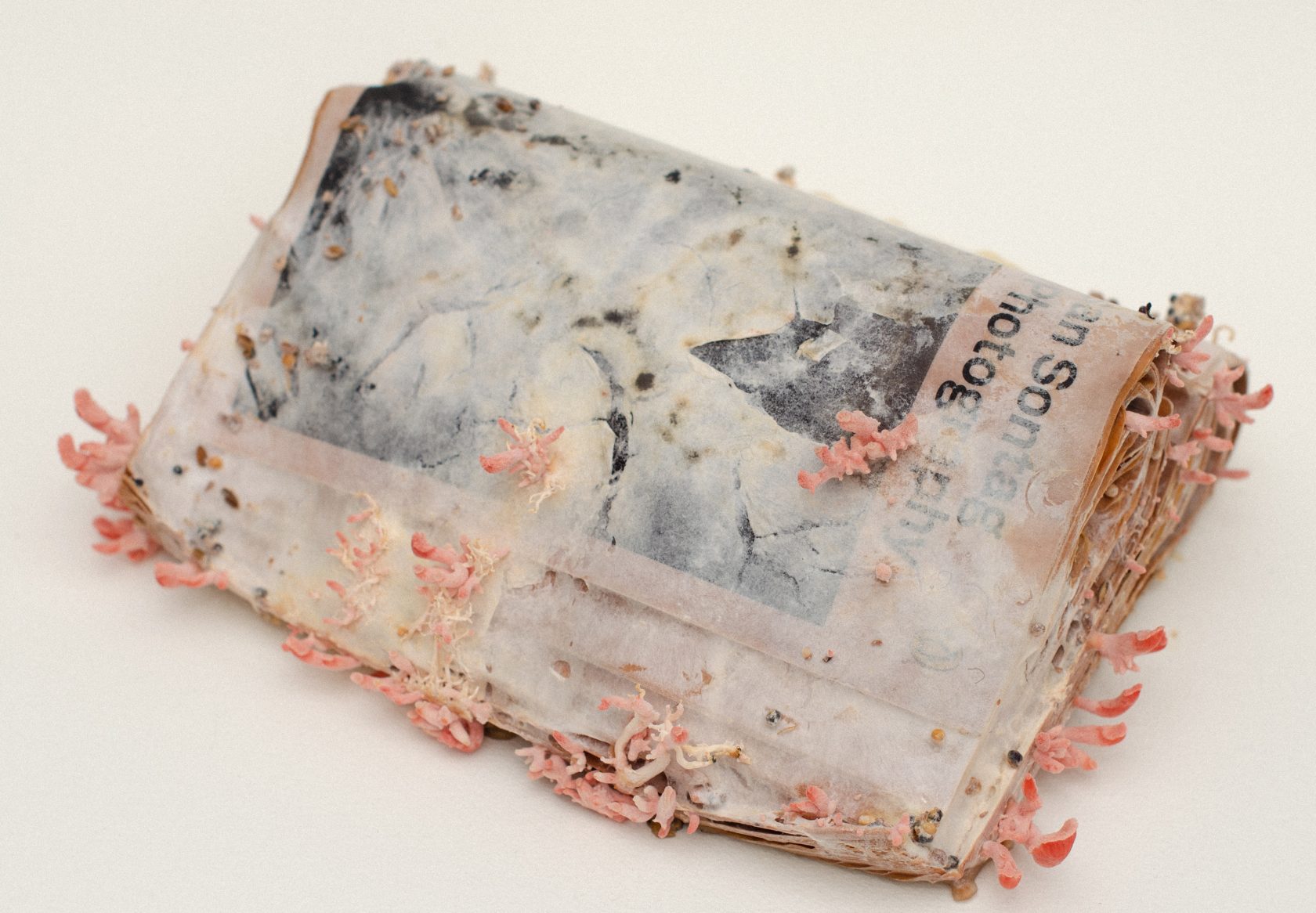

I also created a project where I was growing microorganisms on film negatives. II found out that microorganisms dissolve the silver halide layer that covers the film, and that’s why it erodes.

The film showed constructed landscapes in the Netherlands. When I put these negatives inside this medium where microorganisms grow, they took back control on how they represented this nature. As time goes by, they completely eat away what is on top of this negative and it is just them that remains what we construct to be an image.

Do you often get questioned about the ethical side of your work?

I do this myself! It is something that I explored when I wrote my thesis. Can ecological art exist and what are the ethics behind ecological art? It can never be fully ethical because you are using other parts of nature or organisms of your own making. That is not for other organisms, but for humans.

At the same time art that addresses ecological concerns can foster different understanding for people, which can lead to understanding the environment better.

Would you like to explore the art of microorganisms more in the next few years?

Yes, but not specifically bacteria. I’d love to explore funghi, yeast, and other kinds of organisms you can see underneath the microscope. I am very interested in working with organisms that you can consider the lowest on the evolutionary scale.

Like the water bears that live in our eyelashes for example?

The smallest things are the most resilient! They have also found different living bacteria in the Arctic quite recently.

Does knowledge of microorganisms change your point of view on them?

I am much more relaxed now! Being more exposed to these things breaks the paranoia that you have in the Western world. I love the work of Annika Yi, who works in the intersection of biotechnology, microbiology and smell installations. In interviews she mentions this sterility paranoia and I find it very interesting, this obsession. For me the fear is coming from things you can’t see. You need a microscope to see it and to get more relaxed.

[ A wasp suddenly enters the conversation ] I just spent a month in a place where there were so many wasps… Now it is all good… The best thing is to blow air. [ Puffs air, wasp flies away ]

A lot of times art projects about environmental topics are about representing nature. That is not my concern. I want it to show itself. I think projecting on our environment or other species is perhaps a bit more harmful than working with them.

Looking back, how did the residence at de Besturing help you with your work in the past year?

It was really nice to have this space! I would never be able to work without it. There were a lot of lucky circumstances. Katerina Sidorova and Bertus Gerssen were basically my mentors at De Besturing. And I owe Dennis Slootweg as well Katerina a lot for the knowledge on working with glass. When you start thinking differently you generate other ideas, it is like a ripple effect.

Right now I am looking for a studio! Most of the time I write proposals for continuing my research and projects, and sending open calls for residencies.

And in the meantime?

In September I did a residency back in Lithuania: shepherding sheep for a month. I got to understand how much work it takes to produce materials in a local context. Just to get a tiny ball of yarn, the sheep have to be shepherded twice a day, three to four hours, they have to live there for years, the wool has to be cut, it has to brought to a location to be washed and combed, then you have to spin the wool, and only then you have a ball of yarn.

A lot of times our materials come from other species, plants and animals. We don’t have this direct connection anymore, we we have rifted apart from where they come from.

This residency made me realize how far away I am still in understanding the materials that I consume or work with.