Stroom Invest interviews / artist Katerina Sidorova

On the outskirts of the Binckhorst, not far from the Caballero factory, you will find De Besturing: an old industrial building that was once used as a factory. These days, it provides a creative work space for a group of artists working in a variety of artistic disciplines. One of the studios, filled with an abundance of sunlight, belongs to Katerina Sidorova.

Katerina Sidorova came from Russia to The Hague in 2012 to study at the KABK. She did a master’s in Glasgow (Glasgow School of Art), but returned to the Netherlands and is now working as a professional artist here in The Hague.

She creates works of glass, plywood, stone, textile, publishes books, makes music, all in the best tradition of the multi-talented Renaissance artists.

So how does it work to be the artist Katerina Sidorova? How do you decide at the start of a day what to do? Is it intuition or a strict planning?

Normally everything starts with an idea and a couple of images I use for reference. I do a bit of writing or sketching. This part usually takes more time than creating the work itself. It could take months until I make the actual art work.

As I progress with developing the concept and the visuals, materials become important. They are a big part of how the art work communicates to the viewer.

Take for example the purple and yellow work behind you. This work was for a one night show called ‘The Set‘, made in collaboration with Cathleen Owens for Pip Expo. It is prop like a TV set. I used plywood, wood and paint.

Glass seems to be one of your favorite materials to work with lately. Like in the exhibition of Durst Britt & Mayhew in 2020 / 2021, Gläsener Mensch.

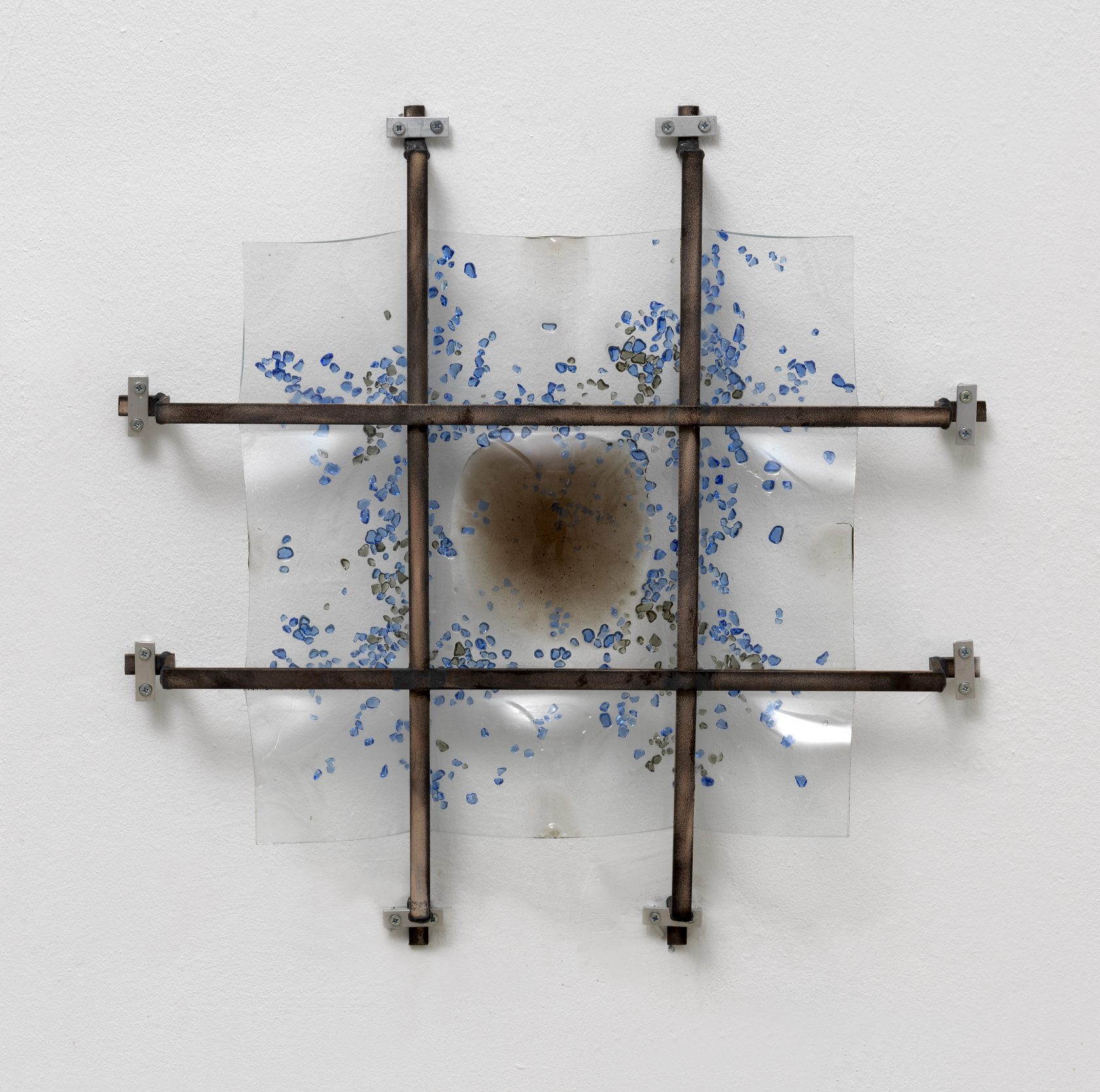

Many of my works are made of glass – for example this long piece that we are looking at now. This particular piece is about state aggression, state power and the fragility of a non-democratic regime. I wanted to make something that could be scary, overpowering and also make it a bit impotent: see-through and fragile. Glass is the perfect material for this.

This other little work here is made of flowers, clay, a bit of plastic and glass wax, which is very similar to sugar cane and often used in film props. This object came from an older work. I was thinking about preservation and memorabilia, especially memento mori: how impossible it is to preserve them. You can see the flowers rot. And change. They are at their final stage now.

I have to be really careful with it! It can break easily. It is at the owner’s risk when I sell it because it will decay much faster than works of glass or metal for example.

The works for Gläsener Mensch were the first big projects I did with glass. A few months before I had a residency at Beeldenstorm Daglicht Eindhoven, now Make Eindhoven: a production facility for glass and print. This helped me by making these large objects, inspired by the protest movement and state repression in Russia. These objects worked very well in a duo exhibition with Wieske Wester.

For me it was great to be able to experiment, knowing that you can invest a lot of time and finances in something that can get shown.

I know the themes in your work are political, but the works are very aesthetically pleasing. Is that on purpose?

I like a bit of a bait game. I try not to think in archetypes. Political art should look like this, feminine art must be that, etc. Not for me! I always enjoy making something very visually appealing and also allow the viewer to stay on that level, or to get as deep as they can.

There are layers to each work. The visual, the material, the technical aspects. There are also political, historical, mythological references. Or philosophical references: these are the most important for me. The larger installations come with a text eventually.

And that’s yet another talent: writing.

Sometimes one medium becomes limiting. There are different point of access for an art work. For someone a text could be more appealing than an art work. Then I am happy to generously provide it.

These are not your typical art theory essays.

With Art theory you are expected to write a lot. But academic writing is very restricting and I would like to have much more fun than academic writing would allow me! I wanted to bring the playfulness, humour, unprofessionalism that I do enjoy in a good text.

My bachelor thesis was my first publication: How to stop being human: Guidelines for becoming a squirrel. It was designed by Leeza Pritychenko.

I had so much fun with that text! Still using good references from philosophy as it should be, but playing around with them.

Writing for me is escaping the seriousness that I have – and seriousness that the art world can have. A good space to allow this side of my personality!

You said playfullness. How do you keep the balance between humour and seriousness in your work?

There can be humour in horror, there’s always pain in a joke. That’s how I see my mind. That is instantly reflected in the work because I made it.

It is not a choice but inherent in how I approach anything. It is just how I function. Many people don’t get my sense of humour… at all!

There are not many things I appreciate about humans, but this side I like: the complexity of us as species. You can never be your best self!

Would you call that view of humour ‘typically Russian’?

I had conversations that some cultural codes were read in my work: it could be a work from Russia. I left when I was twenty and I learned the ways of art making here also. I emigrated quite early on, and that’s why my ‘vocabulary’ as an artist is probably more mixed than people who emigrated being thirty, forty.

I do feel connected to Russian literature. Making narratives is very essential to what I do. Finding strength to laugh at something horrible and absurd in it’s horror, yes, that is something of our culture.

Recently I was re-reading The Master and Margarita thinking of Bulgakov’s relationship with Stalin. He was allowed to stay and to produce plays, but Stalin played with him like a kitten. I never saw The Master and Margarita before as a reference to that situation.

This kind of pain and deeper connection to the world, what is the human role in this mess, is something we do grow up with in Russia. I am really worried with how kids are taught now, with the propaganda and heavy censorship. When I was young, we were taught to think and to feel.

I wonder how boring The Hague must feel for someone who grew up with the Russian culture of the 90’s and 2000’s.

The 90’s and early 2000’s: it was an economical mess in Russia, but with freedom. We had drag queens on TV! We did a lot of punk things in these days. We would go to concerts with friends, run around, be drunk on a frozen river in the middle of the night. It was very free and dramatic, very filmesque.

I moved to The Hague in 2011. It was a corporate and proper culture. Dealing with the smallness of everything was very hard at first. Especially the rigidness of everyone’s routines. You had to make appointments for everything… Be on time, leave on time… You couldn’t go on an adventure. I didn’t feel there was a place I could go and scream.

It was hard to tame myself. I dreamt of escaping. I was really happy when I could do my master’s in Glasgow.

Traveling helped as well. Before the war I would go to Russia twice a year. I had international shows. I was lucky enough to see countries that were not so strict in their lifestyles: Lithuania, Latvia, Czech Republic… There is a similar feeling… The pandemic years slowed me down but traveling was always a great escape.

Over the years The Hague changed as well. I was happy to see the rise of the artists initiatives. And the compactness of the Netherlands is also an advantage: The Hague, Rotterdam, Eindhoven, Maastricht, Amsterdam are all different in how art scenes function, and reachable.

At this point I am happy with this place. I have a studio, I can have shows, and more or less have some income from my work. If I really need to have a breather I can text my friends and I would have a couch and a glass of wine in Georgia, Armenia, UK, Italy…

Politics are the common thread in everything you do. A lot has happened lately in which Russia was involved. How do you deal with that as an artist that is originally from Russia?

I draw a clear line between my political position as a citizen, in which I am outspoken about my opposition to the actions of Russian government, and my artistic practice. With my art I attempt to stay aside of immediate reactions to political events. The red thread that unites all my work is mortality, and the last few years I was pushed in this theme: death at the hands of the state. It has happened so many times in history: non-democratic regimes happen to be everywhere.

For example this work behind us… It is titled ‘Bottleneck’ and refers to a protests in May 2012 at Bolotnaya Square in Moscow. Due to police blocking a narrow passage tot the square protestors became stuck, friction develops, and you can justify the first arrests. An old military tactic. For me this moment was the end of democracy in Russia. I would never shy away from speaking about it, but a work like this would take more time and reflection.

Speaking of what’s happening in Ukraine, I would rather act as a person than as an artist. It’s too easy to take this immediate pain of many people suffering in Ukraine and use it for your own gain. That’s not how good art is made in my opinion. I speak out as a citizen of an aggressor county.

Primary colors seem to be very important in your work. Are they meant to emphasize the (political) narrative?

My Instagram archive is the perfect medium to see how color schemes change from project to project! But I rarely attribute colour to the content of the work.

The first time I used blue as a big backdrop it was an open studio structure in Glasgow. Each of us had a big open corner. They were all white. For me as an installation artist it was really hard to focus: you see white and you see things. I needed something that was out of the context of everyone’s else’s work so that I would have my own mindspace, and I could position smaller objects within my space. Dark navy blue was the strongest color I could find.

I’ve also used a very dusty bright pink for an artwork on a mock execution of Dostoyevski. You almost get this old Barbie pink: Barbie plastic that has been in the sun for a while, so the blue pigment start to evaporate, and you get sickly yellowish pink. It was originally associated with ‘girly stuff’ and it draws the visitor in. The more one stays there, the more this pink is irritating on the eye. Pink can be very attractive, but pink is a very aggressive color as well.

I always like to be slightly off. So primary colors but a bit shifted. At Durst Britt & Mayhew together with the gallerists we placed everything to be slightly off center. Nothing is ever symmetrical!

One of my big wishes for the viewer is to not get too comfortable with my work. Just when you think: this is comfortable for me, then you notice something is slightly off. It is a bit cheeky. Dutch people like cheeky!

Stroom Invest Week is an annual 4-day program for artists who were granted the PRO Invest subsidy. This subsidy supports young artists based in The Hague to develop their artistic practice so that artists and graduates of the art academy can continue to live and work in The Hague. To give the artists extra incentive, Stroom organises this week consisting of studio visits, presentations and several informal meetings. The intent is to broaden the visibility of artists from The Hague through future exhibitions, presentations and exchange programs. Stroom Invest Week 2022 will take place from 7 to 10th of June.