Stroom Invest Interviews / Curator #8 Maarten Spruyt

Maarten Spruyt has been a curator since the nineties. He has worked with the biggest museums in the Netherlands, including Boijmans van Beuningen, the Gemeentemuseum and the Van Gogh Museum. It all happened spontaneously because he “makes something visible that others do not see”. “My work has a lot of subtlety to it that you do not immediately see but that you can feel.”

Your career as a curator started in 1993 with an exhibition in the Central Museum Utrecht. Can you give an impression of how you have grown as a curator since then?

‘Your knowledge of how a museum works from the inside grows day by day. For example, you realize that for your exhibition to open, you only have two weeks to build it. You start thinking: why don’t all of you just work a little longer, even on weekends, for example. But you forget that the technicians go from one exhibition to another and a new one will be opened two weeks later.

‘And every museum has its own rules. The surveillance has its way of doing things, the canteen staff wants it to be done their way, and all of this is different again from how the director wants it to go. Dealing with all these layers I think is fun and interesting, but it can also be very exhausting.

‘I used to have absolutely no idea of something like ‘lux values’ [measure of intensity of light, BS] of the prints, drawings and clothing, needed for its preservation. Or visitors who do not know how to behave in relation to art, just walking across a stage… I can go on for a while.’

Your past is inextricably linked to fashion. Do you have the idea that the transition from fashion styling to setting up art exhibitions has been a natural process?

‘Absolutely! Fashion is fun for its spirit of the times, but it’s not that special. It is a reflection on what’s going on in the world. If the neckline can’t get any lower, or the jeans end almost underneath the butt, fashion tends to go another way radically, such as a turtleneck and a veil around your head. High rise jeans… a logical consequence of the search for innovation. After shoes with pointy noses come shoes with round noses! After the tall plateau pump comes the flat Roman sandal.’

You got a great chance in 2005 with 'Everything Dali' to show your talents in a large exhibition (in Museum Boijmans van Beuningen). Can you tell us more about how you handled such a massive subject like Dalí?

‘I was in the museum often to imagine the space. Dalí painted a lot of sunsets, in which the sky gradually changed its colour. That was my point of departure.

‘It was the first time that the museum worked with a printed gradient on the wall. That was really beautiful! The works seemed to float on the walls.’

‘Consequently, I became convinced in 2012 to try it again in the Van Gogh Museum, with the exhibition ‘Dream of Nature’. Again, the museum was afraid that the colours would dominate the artworks. But the gradient on the walls, at an exhibition about painted nature, is just stunning! This time they were really painted.

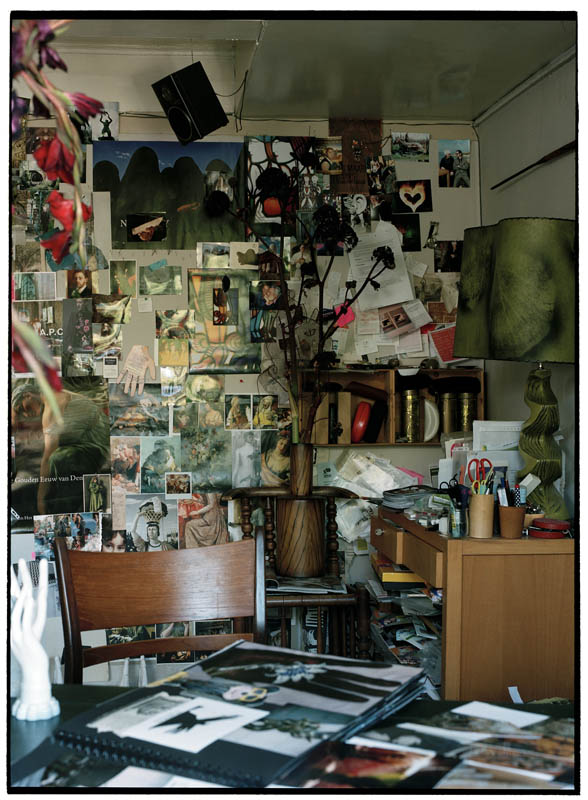

‘An example of how I work can be seen at ‘Prints in Paris’. The request was to show the rich collector downstairs and to show Paris’ ‘ordinary’ street life upstairs. I started reading a lot of books, researched many Parisian things from that time, and taking inspiration from that. Such a process often begins a year before, at the moment I’m asked, with a peak in the last three months.’

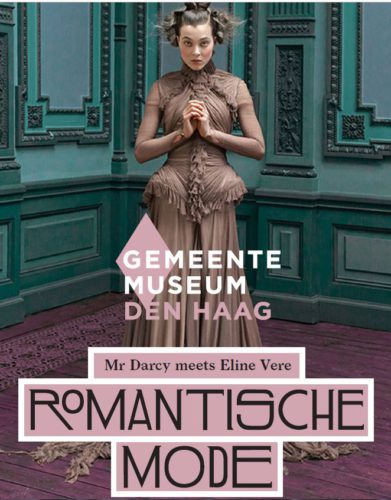

You have also worked with the Gemeentemuseum, for example for the Chanel exhibit, Romantic Fashion, Fabulous Fifties, Voici Paris, Fashion ♥ art. How did this collaboration originated?

‘I worked with Viviane Sassen and Martine Stig on a project for the Wonderkamers. Madelief Hohe saw how I worked and asked me for Fashion NL Next Generation 2005/2006. That was almost an installation in itself. More fashion on the streets with so called ‘wildplakkers’, who also came to the museum to put stickers everywhere. There are places in the museum where you can still find stickers…’

I can imagine that 'fashion ♥ art' (2011) has been a kind of ultimate exhibition for you. In the exhibition in the Gemeentemuseum you let fashion respond to art, bringing together your two most important worlds. Is that right?

‘Fashion can certainly be an art form and there is definitely a link between the two. Women who dare to wear special clothes are often artistic.

‘I have a lot of respect for people who dare to dress differently. It is not easy. People think that you do it on purpose to invite comments, while that isn’t the reason you do it. I have experienced that first hand.’

You said your role as a curator is comparable to an actor. Do you mean that as an actor who plays a role for a film, you play a role for an exhibition?

‘To me it’s very important to dig deep into whatever the subject is. That digging is something I really enjoy!

‘I will go very far in that regard. Certainly with the intense build-up, if you know it will be over again shortly. By then, the subject is almost toxic to me.

‘I will start working on the next thing immediately the Monday after, the best way to leave it all behind. I rarely come back during a running exhibition. But three months are over in a jiffy and other projects have to wait until it’s finished.’

Sjarel Ex once said about you that you make something visible that we don’t see. Do you agree? What do you think is the essence of being a good curator?

‘Everything is about nuance. I would never like to dominate the artworks, nor do any designs that are too loud or too thought-out. To me, the theme is leading. My work has a lot of subtlety to it that you do not immediately see but that you can feel. I believe in layers, zooming in and out around the artwork.’

‘To create 3D from 2D and vice versa, that’s an example of such a layer. Take the position of the Jacob’s ladder next to a real staircase, like in ‘All kinds of Angels’. Or at ‘Prints in Paris’, with prints of paneling, stickers of wooden floors and a rug with a shadow. I put a lot of effort into them.

‘Another example is in ‘Ode to Fashion’, when you see a picture by Sabrina Bongiovanni, with exactly the same doll as in the picture in front of it, so there appears to be depth.

‘I work at my best if I can do what I think is good. Not when someone expects or wants something. Then I’ll lose it.’

Your love for colours is immense. Can you say that a love for colour is essential for a good curator?

‘Colours are very important to me. I live for colours. Choosing colours is always a very intense process, with a lot of testing involved. As with ‘Prints of Paris’, made in collaboration with Tsur Reshef, when beautifully faded colours were used in the rooms.’

Due to your love for colours, there is a lot of personal input from you in the exhibitions. For example, you do not show everything neatly at the same height, or the colour of the background is important. How do artists usually respond to your interventions?

‘Often, gallery owners are more difficult than the artist. But there is still a lot to do. I would like to style art even more. Like you do in fashion when you combine different clothes to create a new image. I could do that much more with art.

‘But be aware, that would be for a temporary exhibition, so you can see that work in a different light, different from what it would look like on a white museum wall. I do that already, but I would like to push the envelope even further.’

Is each assignment a chance to pursue a kind of exploration? Is any new movie, book or piece of music a response to what came before it?

‘Yes, you always respond to where you are now. It is always layer over layer, response to another response. Picasso also looked at African masks before painting. This process never stops, and that’s what makes it so interesting.

‘You can observe it with those successful international fashion exhibitions. First, you have Alexander McQueen and then you’ll see all the influences on the other major international exhibitions. Like Dior, on display now in Paris. Every day long queues in front of the door.’

The question here is whether you as a curator also have to be a kind of an artist to do your job well. What’s your opinion about that?

‘I can only speak for myself but I would like to experience the subject (temporarily). For example, when I was busy with the romantic fashion show about the 1900s, I noticed that only paintings from that time period ‘speak’ to me. At that moment I had more difficulties with 20th Century paintings.

‘Everything I can learn about this assignment about the nineteenth century enriches me. It’s nice when it happens so playfully!’

Meanwhile, the Dutch museums know where to find you for their exhibitions. What would be your advice to a beginning curator? Are there any sides to curatorship that you don’t think of as a starting curator?

‘You should like to interact with different people, not just want to do your thing.

‘You should want to gain experience and give it time. Don’t be too impatient or try to become too big too soon.’

You work a lot with Tsur Reshef. I'm curious about what a design partner has what you do not have.

‘Tsur has incredible spatial insight and knows like no other how ideas can be transformed into an image on the computer, so that everyone can see the final product. Tsur does the technical implementation of plans I’ve been brooding on for a while. I do not really work on the computer, but if Tsur does it, the plan is suddenly visible. We differ greatly in that.’

If someone offered you an unlimited budget for an exhibition, what would you like to try?

‘Making installations with nature-related subjects. I love the beauty and perfection of nature and that nothing is as straight as an arrow.

‘The quality of an exhibition depends on many factors, especially how free you are, and what the requirements of the employers are. But expressing your enthusiasm for what you do always helps.’

Poster Romantische Mode © Koen Hauser