Invest Week Interview #8: Sissel Marie Tonn

Sissel Marie Tonn (1986) ended up in The Hague after finishing her bachelor in Copenhagen, working for three years in Toronto.

She likes to work on projects requiring a long haul. Complex issues like the earthquakes in Slochteren or oil spills in Canada. ‘For me it is interesting to uncover relations that are not immediately obvious.’ We discuss them in her sunlit studio near park de verademing.

How did you end up in Toronto, and then in The Hague?

‘I finished my bachelor at the university in Copenhagen and I did my final year at the university of Toronto. In Canada I worked for an organisation that tried to make a more inclusive design for social housing. And I was working as a videographer, freelance stuff. At some point I thought: either I stay here, forever maybe, or go back to Europe and take a shot at what I really want to do.

‘I stayed in Berlin for a while applying to the Universität Der Kunste, but I didn’t get in. I send my portfolio to KABK in The Hague and ended up getting in there. I got in this master’s course with a strong theoretical component, but I was actually spending a lot of time with people from Art Science, who have a bit more of an experimental approach, with strong affinities to sound and self-build media.

‘I really enjoy being in The Hague, I found a nice community here. There’s a lot of experimental art practices. People do exciting things using many different media – bacteria, for instance.’

One of your projects in Canada was a film about an oil spill and its consequences for the environment, especially mushrooms.

‘I became really fascinated with what they call in anthropology ‘intimate knowledge’. Embodied, intuitive knowledge of the environment, like farmers have with the weather. The mushroom collector gave me an entryway into a very problematic discourse in Canada regarding the oil infrastructure. It was a great way for me to deal with something so large while maintaining an intimate focus.

‘The mushroom collector wants to collect mushrooms, but he can’t, because he knows they are contaminated from the oil spill. The work becomes a visual acknowledgement of this relationship. A clear relation emerges between extracting fossil fuels using fracking fluids in the Bakken Formation in North Dakota, bringing that 1000 kilometers to Lac-Mégantic in Canada, and it all spills out, and gets sucked up in these mushrooms, and someone can’t eat them.’

Are there any similarities with your other project, researching the earthquakes in Slochteren?

‘I wanted to do something more local, something that’s not as far away as Canada. It’s also an interesting way of getting acquainted with a country that you don’t know. I went to Slochteren and I got in touch with some retired people there, and they ended up letting me stay for a week, really… gastvrij.

‘I am very interested in the questions from the scientific community versus the people who live there. Both have a very different perception of what’s happening. The people who live there for instance feel a very strong somatic experience of these earthquakes. Even though in scientific terms they are not so strong.

‘There really is a material connection between Slochteren and using the gas in our homes. We are all part of the same ecology, and there are consequences to all of our activity. The two works are similar in the way that people respond to environmental change. They deal with them through this very visceral relationship to the environment, undergoing either subtle or profound change.

‘There’s a whole lot of social and mental issues that tie into the objective fact that the earth is shaking. That is interesting to me. It is not scientifically possible that these people wake up before the earthquakes happen, because they are not that strong. But they still say they wake up before they feel the earthquakes. This is part of their reality and this matters to me. How can you give that as much importance as the scientific facts?’

But your plans were ironically ruined by your own, private earthquake…

‘Yes, I got a concussion, two months before my graduation, because I got hit in the head by a mirror from a bus… Be careful with those mirrors! [Laughs] I was working with all these shakes in the ground and then I had this earthquake in my head…

‘And then all my plans had to change because I couldn’t use the computer at all. Every time I looked at the screen, I felt sick. It is something with the flickering of the light.

‘I ended up writing a field guide (The Field Guide to Attunement of Bodies) with all the different observations and thoughts I had collected, staying with these people and also with the people in Canada. I wrote it on a type writer. It wasn’t like a hipster thing! I was in a dire need. But it was also an interesting material shift. It really challenged my way of writing – which was a good thing.

‘My whole idea was to make this earth vane, this machine, monument. And then I would install it in Groningen where it is actually happening and make a film. But I couldn’t go back, couldn’t edit, so I ended up just making this sculpture. Which was fine, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do with that project.’

How were the responses to the earth vane?

‘I haven’t been back. The whole project got a bit stalled because of my injury. In the end it became too much of an entertainment, and the context got a little lost. I think it was somewhat too much of an art object.

‘For me it is more about the issue of humans having the capacity to make earthquakes. There is this Indian historian, Dipesh Chakrabarty, who uses this phrase: ‘Humans have become geological agents.’ With the sheer amount that we are and we consume, it has the same impact on the biosphere as an ice age or a vulcano eruption, so that’s worth thinking about. It has a lot of artistic potential.

‘The process of sonifying the earthquakes (the transduction of the soundwaves from one material to another) is really interesting, but not very much connected to the discourse of the earthquakes. Making an archive of all these earthquakes in Groningen, where people can come and feel them on their bodies, would be so much more effective.

‘I need proper funding so I can go back and stay there for a while! And I want to work more with how you can use these earthquake recordings as material. How can they be made into an archive that you can experience?

‘These earthquakes are in a sense cultural phenomena, showing that the distinction between culture and nature are inseparable. They are now part of Dutch heritage!’

You obviously have a special fondness for theory and thinking about art and art related subjects. Does the theoretical part appeal more to you than the practical part?

‘I have a big fascination for art theory and philosophy. I guess I feel a little bit in between the theoretical and the practical part. That can be uncomfortable. But as you produce more work, and you have some confidence in your work, it becomes easier.

‘I just did a re-edit for the film with the mushroom collector. I was engaged with this idea how the different elements of society are interconnected. For instance there’s a philosopher, Felix Guatteri, who spoke about ‘the three ecologies’.

‘There is the environmental ecology, but also the mental ecology, with all the mental aspects that constitute you, and then you have the social ecology. His main idea was that if you aim to solve problems related to one ecology you can’t separate one from the others.

‘I really believe that you can seemlessly bridge the gap between thinking and making. And that was the whole deal in artistic research that you have these different tools and you use them.’

Do you sometimes feel you are overthinking your work?

‘Oh, yeah, every aspect of my life I am overthinking, that’s no secret [Laughs]. But it is not always like that. This last work I did with my partner (artist Jonathan Reus) in Madeira was not thought through at all. We just went there and we made something. A fresh approach.

‘The main reason to go was this really old forest, one of the few primal forests in Europe. Constant submersion in the weather, since it’s covered by clouds. It has the feeling of being in the midst of the changes in the environment.’

This picture is a result of your trip to Madeira. Can you tell us what we see?

‘We tried to make these different sensory filtration devices. What he’s wearing is a sensor glove that plays back the bio-signals of his body. This thing on his head is a wind periscope, the wind is directing what you get to see and get to smell. The biometric sensors transform the unconscious responses in your body into sound. So in fact you are composing with the environment.

‘These sensor gloves gather data of the fluctuating signals of your autonomic nervous system. We called the project cartographies of human sensation, which plays on the idea of temporal cartographies. You can make a data collection of the place through this technology.

‘We also have these glasses that change your perspective completely, they go out to the side like a bird. If you wear it for a long time you will get a completely different perspective of your surroundings, and your brain is plastic enough to change into that.

‘I am developing new prototypes, modules you can put on to your body and you can connect. You can experience these different gradiations of vibrations, a wearable version of the earth vane that translates seismic data into sounds, but this will be sort of worn, like external organs.’

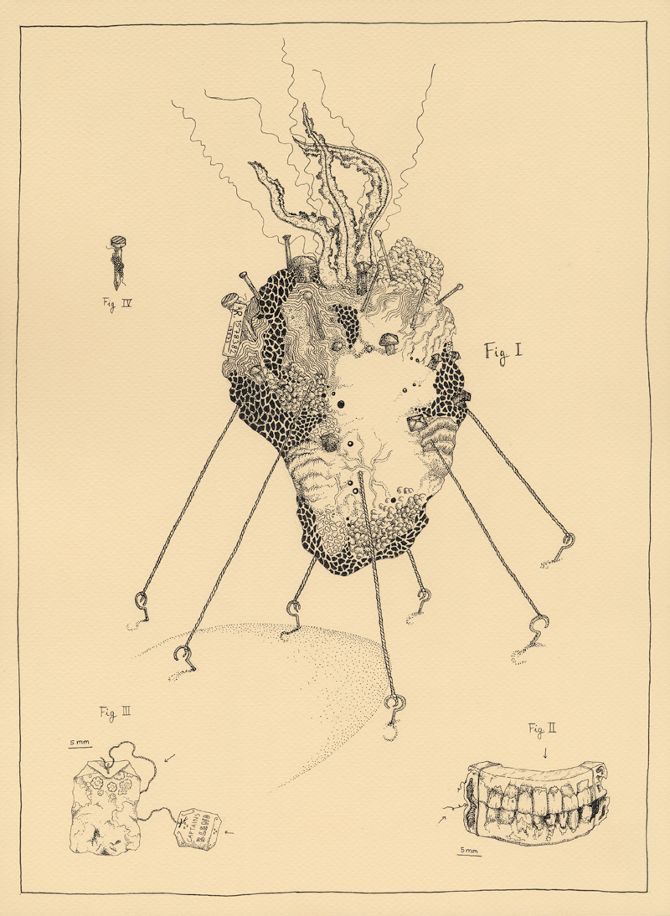

That’s a drawing book?

‘Yes, I draw a lot as well. I mostly don’t even consider it my art practice. It’s not difficult enough for me [Laughs].

‘Especially my mom says: you should draw all the time! And I am: mmm… I need the difficulty of making it work with other people…’

All pictures © Sissel Marie Tonn

Edit 11-4-2017: Sissil Marie Tonn won the Theodora Niemeijer prijs 2016 and has a solo exhibition in the Van Abbemuseum. The exhibition runs until 30 april 2017.

In aanloop naar de aanstaande Invest Week in juni presenteert Jegens & Tevens in samenwerking met Stroom Den Haag een reeks persoonlijke portretten. Meer informatie over de Invest Week is te vinden via www.stroom.nl.