Stroom Invest interviews / artist Joeri Woudstra

Between the trams riding to the Holland Spoor Station and the prostitutes of the Geleenstraat there is a new artist collective: Trixie. One of its members is Joeri Woudstra (1993), alias ‘Torus’. In his studio at Trixie we speak about his most important subjects: melancholy and outdated technology. The common thread in his work is his own intuition.

How long have you been here at Trixie?

About 9 months now. This used to be an old showroom for cars. We emptied the place and put these wooden panels up. I mainly work on my own but we do organize things together in the gallery space. For example, we have an artist in residence for two weeks right now.

When researching your work, I noticed that one magazine calls you an artist, graphic designer, art director and musician. Another magazine calls you a DJ, photographer and web designer. And yet another magazine says that you are a fashion designer.

I guess I am good at picking up new disciplines. In the first year of the Academy I spent all my free time visiting all the workspaces. I tried to understand every machine before I started working. That’s how I taught myself being agile with new techniques. Within all those things you’ve just mentioned, some apply more to me than others. I am not so much a fashion designer, but rather a stylist who dresses himself. I’m no longer much of a graphic designer either. I don’t think I have accepted a graphic assignment in a year now.

For someone who takes on so many disciplines, your studio is incredibly tidy.

I think that’s from my time as a graphic designer. However, I’m also here to let go of that a bit. I have always worked intuitively but now I can adjust things while creating a piece here. It used to be that I’d create everything for an exhibition or commission and then assemble it on location.

Is letting go sometimes also a reaction to your education?

Maybe it is. I would often go against the assignment at the Academy anyway. First I did Willem de Kooning Academy for two years but I couldn’t settle there. In contrast, The KABK was much more about cross-feeding and I was welcome at every department. What I think was a bit problematic though, was the way in which the Academy steered the content of our work. By that I mean the trend that you have to feel politically engaged with topics chosen by the Academy itself. I thought: why are you telling me what opinion I should have and on which topics? I really wonder if the people who make political statements in their work benefit from it. Maybe they just find it aesthetically interesting? What does a cartoon about Donald Trump solve if it will be presented within a group of elite design fanatics? Everything is political, but in my work I try to comment from my own perspective and only if it adds something substantive to the work.

Has there been a transition in your work towards more political content?

I have problems with authority. If someone tells me to do something, I wonder why someone thinks I should do that. Now that I work autonomously, political questions and opinions come up automatically.

Are all these disciplines interwoven in your art?

Yes definitely. There is one distinction though. Torus is an alter ego of Joeri Woudstra and Joeri Woudstra is an alter ego of Torus. Torus is my musical project. There’ s a lot of visual art in it, because I create all the artworks for it, write all the texts and make the designs. I do often collaborate on live performances with my good friend and light artist, Nikki Hock. For my own work I don’t want to solely make music. It is also sound. I made a video of thirty water slides and it seems as if you hear the sound of running water, but that’s actually the wind through the trees. That is also sound.

You are talking about Cylinders of Puberty. How did you come up with that idea?

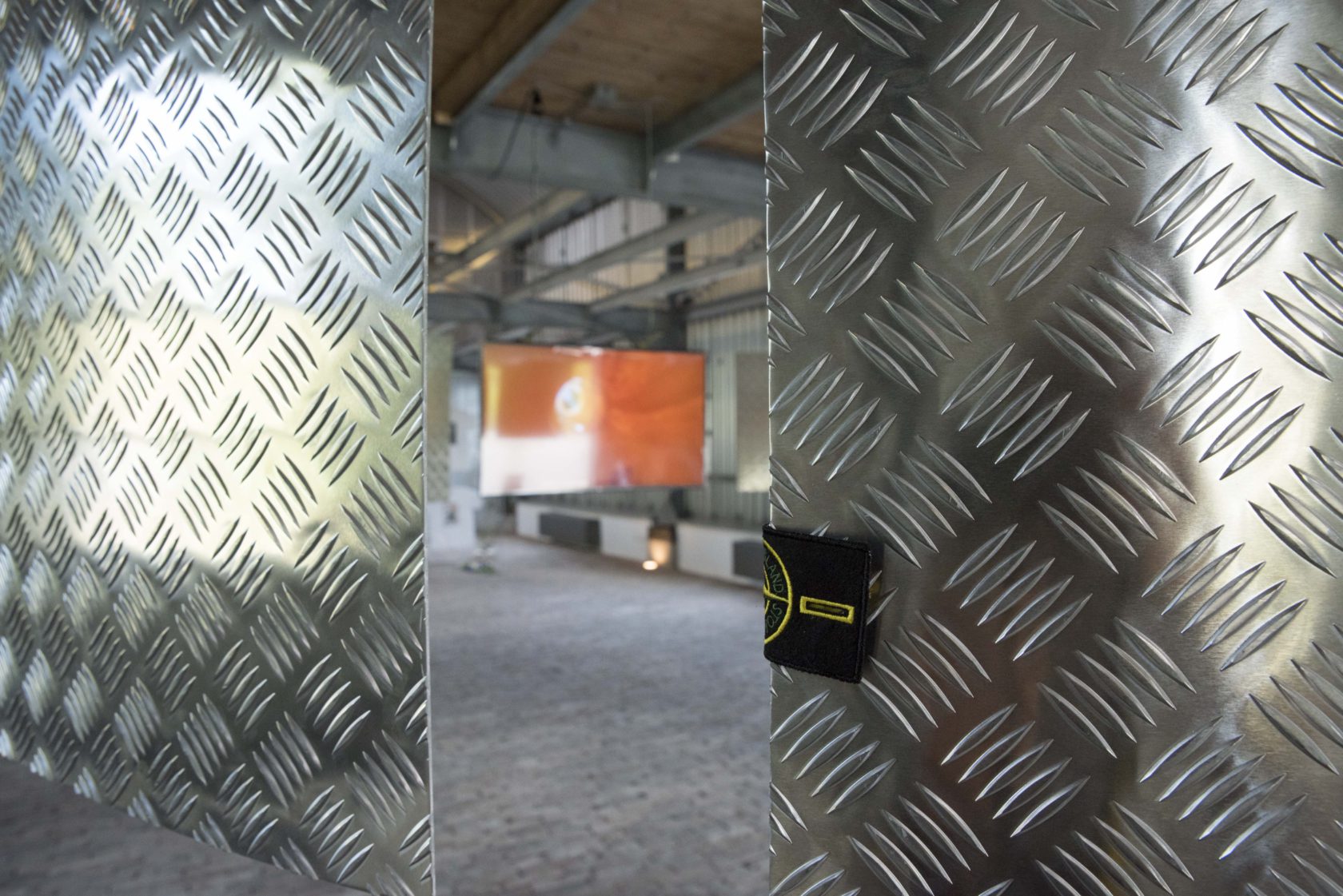

One day I came across this YouTube channel of someone who makes first person videos of water slides. All of these videos have two million views. Some parts of these videos appealed to me visually, some less. However, from this material, I made the ultimate water slide video. I edited twenty of the nicest water slides seamlessly together. A version was shown in an infinite loop in De School in Amsterdam. People experienced that loop as claustrophobic. It’s good to see how all sorts of parallels to modern society were drawn after this work had been created. For example, the way we are trapped in capitalism, which creates things like water slides, sometimes feels like an endless water slide itself.

I do see a connection between water slides and fairs, which by now are inextricably linked to your work.

My music certainly has a lot of “fairground sounds” in it. When I play my music, I use many samples that the owner of a fairground ride would also use. Attention…Here we go! I play them in my DJ set or in a live performance with my own music.

Do you visit fairs? And do you experience them as an artist or as a regular visitor?

If there is a fair, then I’ll go there and try to experience it as a visitor. There is something about the combination of commercial culture and the air of melancholy presented there, that interests me. Even as a child, I would often go to fairs. For example, the big fair on the Malieveld in The Hague. I started using samples of fairground sounds in my music four to five years ago. That was a weird point of reference, taken out of its context, for the people who listen to my music.

Fairs are pretty ugly, I would say. Do you feel attracted to that ugliness?

I would sooner say I am attracted to things that emerge from mainstream pop culture. Certain people from the art world would call it low culture. In my view, a fair is also a form of beauty, although I may use controversial, ugly elements to emphasize a certain beauty! It lets me experience a melancholic sense of recognition.

Can you tell a little more about how fairs are reflected in these two works of art before us?

If you go to the fair, there are attractions that depict celebrities. They want to show well-known people, whose faces have become visual symbols of pop culture. In this work I have portrayed Mariah Carey and Beyoncé. I have made their most famous features unrecognizable by adding a contrasting image to it. For this I used things like lens flares, to make it visually more attractive, something a fair does as well. I made a sheet of aluminium with POP rivets placed into it, as if the piece had been directly removed from the attraction. I didn’t airbrush it myself, but asked people who usually airbrush fairground attractions. Now I’m busy with a work about Treasure Island in Scheveningen, which was a permanent kind of fair. The moment they went bankrupt, the whole island burned down. I can use that for my work.

In your work you appeal to the millennial’s love of 90s nostalgia, but in a way that I, from generation X, can also grasp it.

It is from my perspective, but certainly not only from my generation. I definitely don’t want the give attention to specific phenomena of the 90s. For example, an exhibition at Stigter van Doesburg that opened recently, shows work of mine that has been inspired by medieval visual culture and symbolism. Furthermore, my solo exhibition in Vijfhuizen in 2017 was about recent technological developments. I played with the idea that the moment something happens and the moment you feel nostalgic, almost become equal. I try that by emphasizing an absurd aspect of new technologies. This way you create a similar kind of distance that would normally occur when time passes. A good example of this idea is the curved television. I made an installation with nine connecting curved pieces of metal that completed the circle of its curve.

That sounds like a technological invention that wasn’t invented, but could have been.

I find it very interesting to see if people can feel nostalgic about something that has never been. Or about something that is going on in the future. For example: the Blade Runner movie has many futuristic elements.

That is nostalgia that takes place in a hundred years from now. Things that are introduced in that film that we don’t even know will exist, will have already become obsolete in those days. It feels weirdly recognizable. Back to the Future is another example of this feeling. How does the future become nostalgic over time, perhaps through a shift of the common idea of what the future will look like.

When I did research for this interview, I saw that nostalgia nowadays plays am important role in essays about culture. The past ten years have even been declared “re-decades”. Do you think it has something to do with the overkill of images for the last twenty years or so?

Perhaps. Nowadays we get so much information that we can’t remember anything. Our generation is part of the transition from a time when we could still remember things. In my case my work is not necessarily about nostalgia, but about the feelings created by nostalgia. A curved TV is also not immediately nostalgic. It’s also the banality of a piece of technology.

An artist like Joseph Cornell was also preoccupied with nostalgia – in the 1930s and 40s.

I think nostalgia has always been a thing in art and beyond. Artists who were engaged with this feeling, perhaps did not have the frame of reference that we have now and were perhaps also not as concerned with the emotional value of it. Pop culture and the dissemination of information was of course very different then. Because of the recognizable value of nostalgia, it stirs something deep within people. I think that contemporary nostalgia has a deeper, human layer, even though it stems from things that are not necessarily human.

I think melancholy must come from an emotional source while the art world, in my eyes, often suffers from a too intellectual approach.

I was already wrestling with that idea at the Academy. I noticed how they wanted to teach students to work from reason instead of feelings. I noticed however that I benefited much more from working from my feelings. So weird. Nonetheless, an advantage I got from the Academy’s approach is that I can structure my intuitive thoughts much better now.

How then do you notice that the audience likes this emotional game with melancholy?

Sometimes there is a misunderstanding that I want to make works that are sensitive to a particular time. To me, it’s much more about the feelings it generates. Last month I did another two music performances with a friend from Bordeaux, Barbara Braccini (alias Malibu), who also bears a lot of melancholy in her work. After performances people come up to us and tell us how touched they were about our performance. Media and pop culture are, as it were, like a vessel to me to present that more sensitive layer to the public. And it works, because people can relate to it emotionally. By the way, I call my works paintings. At Documenta14, and again together with Malibu, I made a stack of 360 degree speakers with an audio loop called Technical Painting 1. This way we emphasized the visual aspects of something that was not meant to be seen. The absence of a visual foothold can be, like in this particular instance, very much shaped indeed. In fact, they leave a strong impression because there are so few visual supporting points in a club. Only when someone comes up with the idea of how to draw all the light from a room, can you shape a “black cube”.

I feel you have a lot on your plate.

It can be a bit busy sometimes, but I often look for moments that I don’t have to do anything at all. I lie down on the sofa or take a stroll outside. Most ideas come when I don’t have to do anything. Being able to do nothing is a gift.

Many people stare nonstop at their smartphone and no longer have any room for daydreaming.

I notice that too. I also use my phone a lot. I notice that when I put it away, ideas come without much effort on my part. Only, as soon as I have an idea, I have to take out my phone again to make a note of it.

Maybe use a notepad next time?

That feels nostalgic. Maybe I should do that.