Constructing a Mouse’s Skull @ SIGN – part 2

Part 2: Actualisation

The current exhibition a Mouse’s Skull presents works from Elif Satanaya Özbay, Jaehun Park and Tomasz Skibicki, concluding a working period at SIGN Gallery. Our reporter Michiel Teeuw traced their process, and together they discussed virtuality, actuality, construction, accumulation and working itself. We continue with part 2: Actualisation

After our first interview on zoom, we now meet in the workspace of SIGN.

I ask Jaehun what happened since last time.

JP: “We transported all the artwork materials from Amsterdam to Groningen, and came here. The three of us tried to find the best place for our own works. Tomasz’ work was difficult to install, very challenging. I want to show one of my works on the bigger screen, so I took over the dark room. Elif wanted to install her work in the front of the space. At the first meeting, when we came here, we decided around fifty percent. We wanted to make a sculptural, raw hardware look, a construction/ deconstruction site vibe. Sharing a common sense with each other. Somewhere in the place we’re still reacting to each other with locations in the space, and ways to display the work. The work is almost the same, but the way we display the work with the three of us has changed, I think.“

I ask Elif what she’s working on.

ESÖ: “Today I really wanted to focus on exploring the space. The question is how the elements are going to interact with each other. There is this hair piece, which is very physical, and there will be a video. Am I going to separate these two from each other or are they one piece? Also, the moment that I brush the hair, a lot of hair comes out. I want to place those hair clouds somewhere. But I’m working on a video today, and the sound piece is really important. I’m kind of back in this screen right now.”

I ask her how this screen compares to the hair braiding.

ESÖ: “The physical is kind of like a treat. I feel like I can actually touch that; a repetitive movement, a specific task. Whereas writing and going over text are very speculative and ghostlike. You can go all ways, you press delete and it’s all gone. So there’s things that you can kind of experiment with, but not get direct results.”

I wonder if the digital can ground in the same way as the physical. Elif tells us she’s not a very grounded person to begin with, and rather would be at different spots at the same time. “But it is strange, a screen, it’s this very real and unreal thing.”

I have to think about Tomasz’ preparational work on the computer, and ask him how that felt for him.

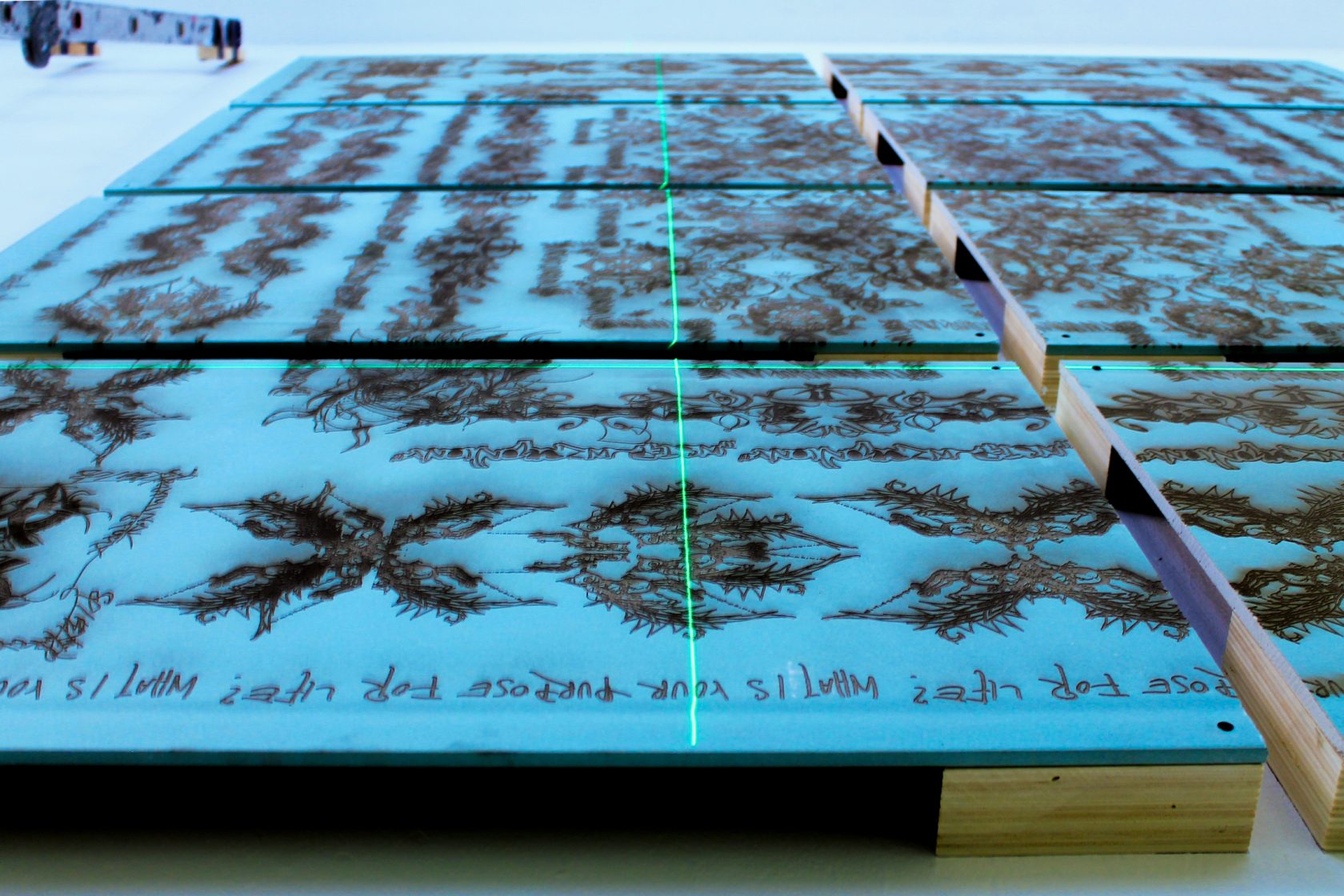

TS: “I think the whole starting point of this work is important. It’s this found script, for a rowdy, teenager angsty junk movie, all written in Polish (my native language). A collection of writings and drawings that I found in an abandoned building in Amsterdam. The first impulse was, this needs to be preserved, or this needs to be continued. Extracting all the drawings, and placing them in this mirrored way. Putting this chaotic train of thoughts and ideas into order and translation, and deconstruction. It’s also related to this blanket, that I have known forever, my whole life. My mom said it’s from my great grandparents, from Ukraina, which I kind of don’t believe, cause it would be more than a hundred years old.

One considers me as a sculptural artist, and the activity was mainly behind a desktop. I found it very relaxing to work on a screen, because what I’m doing most of the time is moving shit around, like a builder. Machines, Cutting, Wood, Dust, Screws, and so on. So this activity was like.. (sighs). I go to my studio, sit down at my laptop, and construct those things, in Photoshop, InDesign, Illustrator, and so on. That was meditative for me. It was a valuable action because it’s so different from all the other activities that I do.”

JP: “For me, all of my works start from the digital space. But the motivation is always from the physical space, finding some construction materials or natural material, like a cloud, wind, snow. Everything starts from natural phenomena or artificial objects. Then I make a sketch, and then I start the digital work. And then from this process, the digital making process, there is already one translation happening from actual work to virtual world. And when I come to the project space or white cube space, another translation from the digital work to the actual/physical installation of work. So it’s a double translation moment.

In the virtual, in 3D space, I can do everything. There’s no limitation, except the CPU/GPU power. I can manipulate everything, I can scale up and down, I can use any materials that I want. But in the physical space, there’s always a limitation, and also my body limitation. When I want to make a hole, I need a strong muscle and proper tools. The limitation happens in the real world, but it also pushes me to make a more creative moment to overcome the limitation.

I’m curious how the physical and the digital relate to the “third space” of the mind.

JP: “I always thought, whenever I see some artist, what kind of graphic card does this artist have in their brain? Because everybody has different recognition of the space, and different spatial recognition. Our mindset is not 2D or 3D, it’s a weird one. Time, space, memories, smells, humidity combines. It’s all these weird senses combined together. I thought it’s more close to my mind, this virtual 3D stuff. But also the actual hardware is in other dimensions. You can touch it and feel the actual scale. The physical limitation itself is the reality itself.”

What about impermanence and the permanence in actual physicality?

JP: “It is very tricky, it means that it has some physical limitations. It is also always a start from the time and space. There is no exact starting point and end point. But I believe that every single object is connected to each other through time and space. When you prepare one pipe, you have to find another bracket element with the same size. It’s a matching process of the size. It came from limitation, but when you find some sizes exactly matching, it’s a coincidence. It is a coincidence, but I want to say, it’s not coincidental, because every artificial thing is made by human, so it has this human size, like an elbow size or our head size. Every mass produced object came from idealized human scale. Everything is standardised.”

I propose to retrace the tour that Tomasz gave in the first part, now walking through actual space. We start outside again. It is sunny and there is a fresh breeze.

TS: “You have these two windows, and this 45 degree entrance. Former butcher shop. We’re going to have someone tomorrow who will relocate the lights. We’re going to have two neon tubes over there. This circular ornament will be highlighted.”

ESÖ: “This is my working area, where I’m preparing. The left side is where the braids are being connected. Here, a net is being shaped and coming together, in different braids. They’re all different sizes and weights. The way I connect the knots is by burning them. The right side is what needs to be braided.”

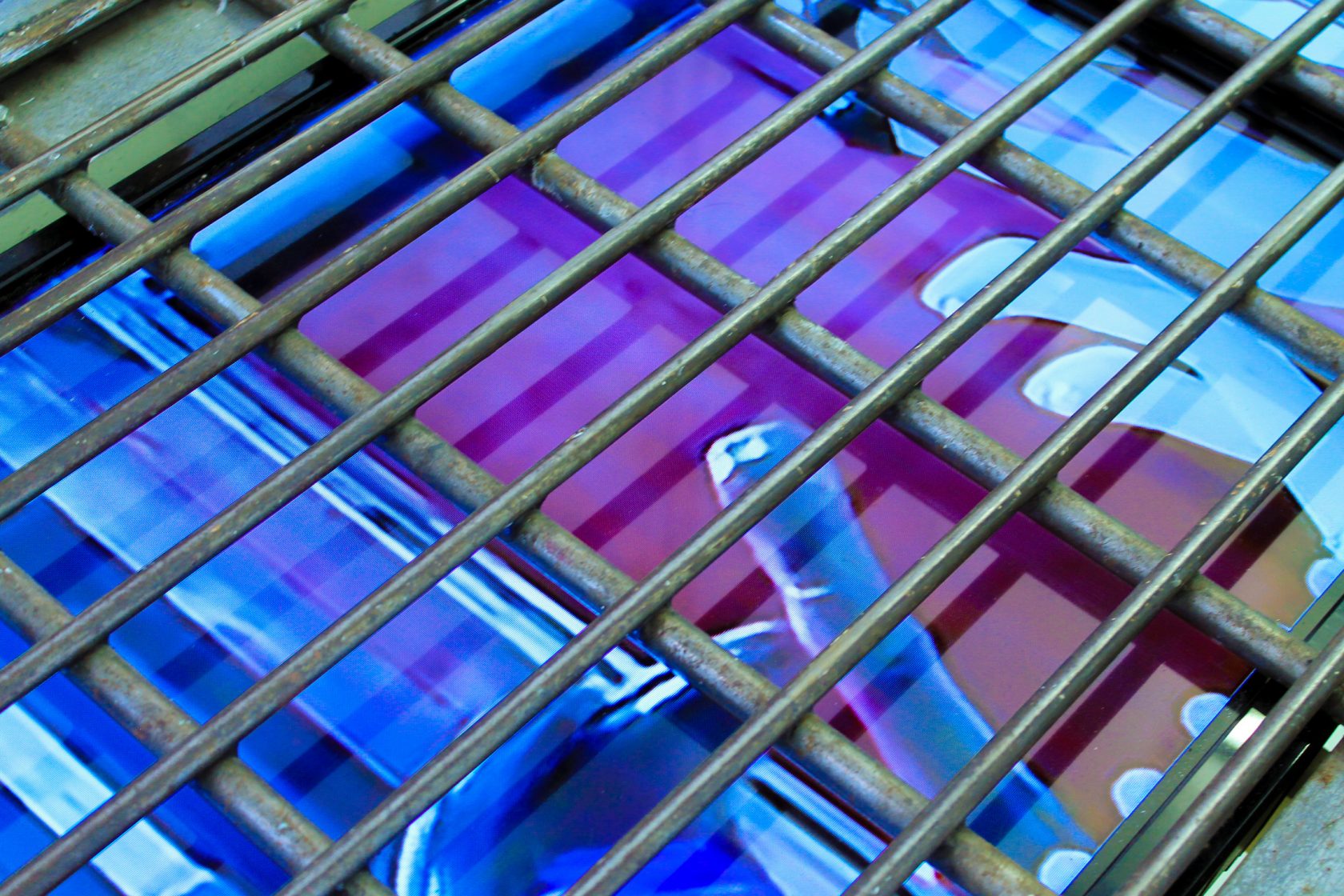

Further in the space, under the grid, we find Jaehuns screens. He thinks about the previous butchershop function of the space. “Some meat, some flesh is cutting down here. It is a bloody grill space. And here, the symbol of capitalism, the mannequin, tumbling around. When you touch the revolving door, it just stops all of a sudden. You’re stuck inside. This liminal space for the shopping mall becomes a jail for a moment by the electric sensor.”

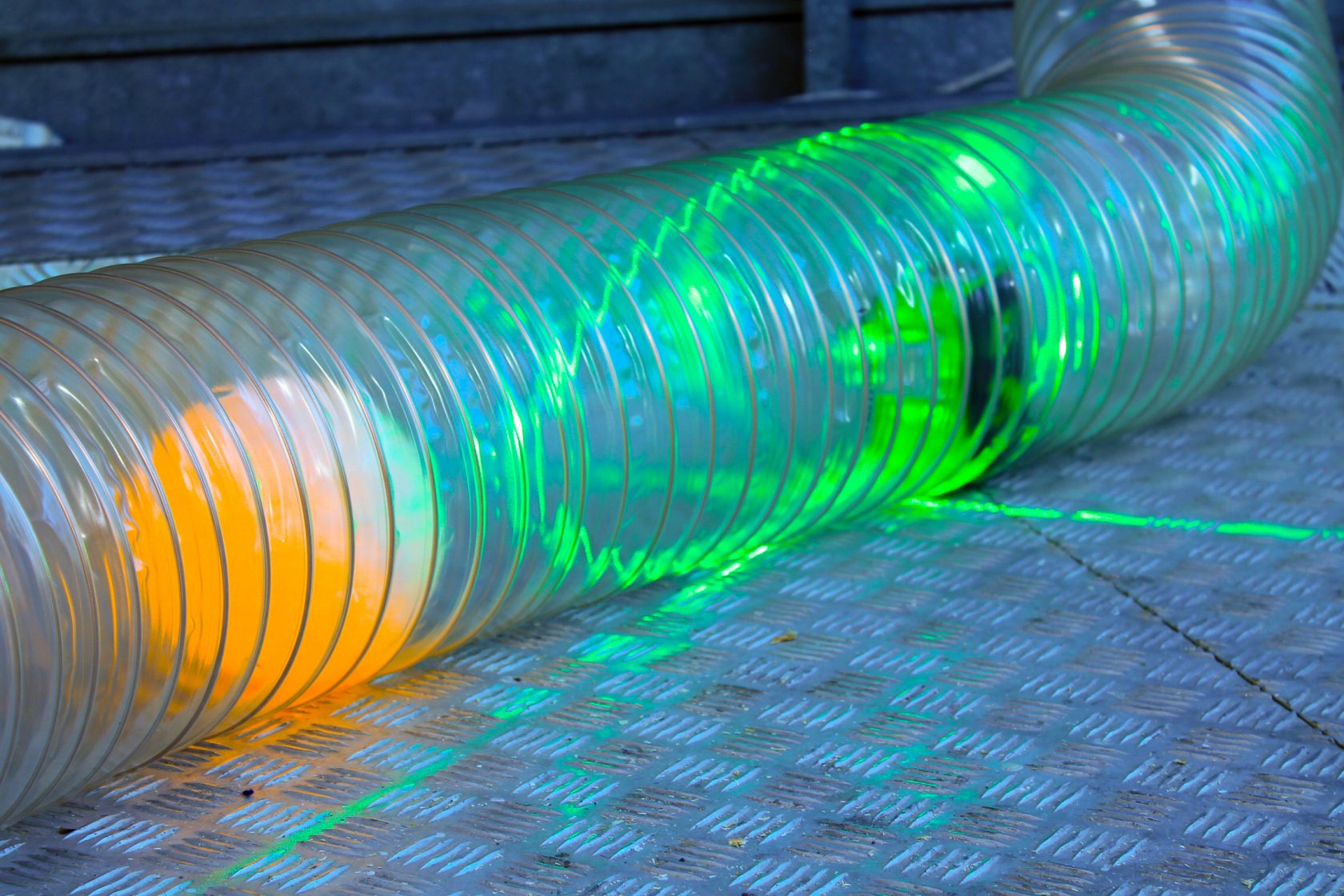

We walk further to the garage backspace, finding a ladder, a carpet, a tube and various videos- one of them showing a near-perfect sphere. The same circle, a light-emitting sphere, is found in the installation.

JP: “Always in digital space, everything is so slick and perfect. So it becomes very graphic. I always intentionally put some noise, some scratches on the floor. This looks more realistic in the virtual space. But here, in the actual space, imperfection is just imperfection: there are no perfect objects and material. Everything has a glitch, scratches, and is weathered. They’re totally opposite to each other. ”

We exit the room again.

TS: “This space is now full of stuff right now, I hope we can clear it up and do something in the space. It’s an amazing space as well, a sort of limbo with a lot of doors. It’s a very dense and productive space, you have a lot of options. Maybe also like a thought limbo, cause it’s the area where you’re on the computers as well.”

ESÖ: “It makes you question your own work and how you want to put it together. Initially, I had an idea of a final product, which is always a very perfected version. But you never reach that. So I came here with an empty head and really just responded to the space. This can be really intriguing if you let it happen. It takes away some pressure, but it adds another pressure- you have a lot of new options. Choices gotta be made, and I don’t like that. I just want things to make sense along the way. Somehow that’s a luxury that I can’t afford every time.”

We walk towards the staircase. Tomasz installed his work yesterday- a big tapestry consisting of a plasterboard structure. Tomasz describes how this material is used to build walls.

TS: “It’s an easy and temporal way, where you just build this metal structure first, screw these plates in, plaster over it. It’s an extremely strange thing to do, setting up walls, out of this extremely sensitive material. You can literally punch through it. ‘Let’s pretend we separate a space’. The wall behind the tapestry is one big multiplex wall. It has been drilled so many times, that you sometimes have spots that are just filled up with plaster, with hole filler. You drill into something and it’s dusty and loose. You are aware of these couple of decades of drilling. It is interesting in retrospect, but it was very frustrating”

He describes how, when you walk down the stairs, the perspective completely changes. How you completely feel different. “Usually you pass things horizontally in a gallery space, you walk past it. In this situation you go down vertically. When you look at it from below, it’s suddenly very up close. You scale bodily, changing to that moment. Oh shit, I’m so small!”

Once we reach downstairs, we sit down and I ask Jaehun to conclude our text.

JP: “I would like to finalize with our show title The Mouse’s Skull, to go back to the first moment. These tiny brains, I thought about this exhibition space. Sometimes I capture these mice, but I never think about what the skull looks like – I’ve never seen it inside.”