Queering, Languaging, Bodying – in conversation with Alice Slyngstad & Oliver Doe

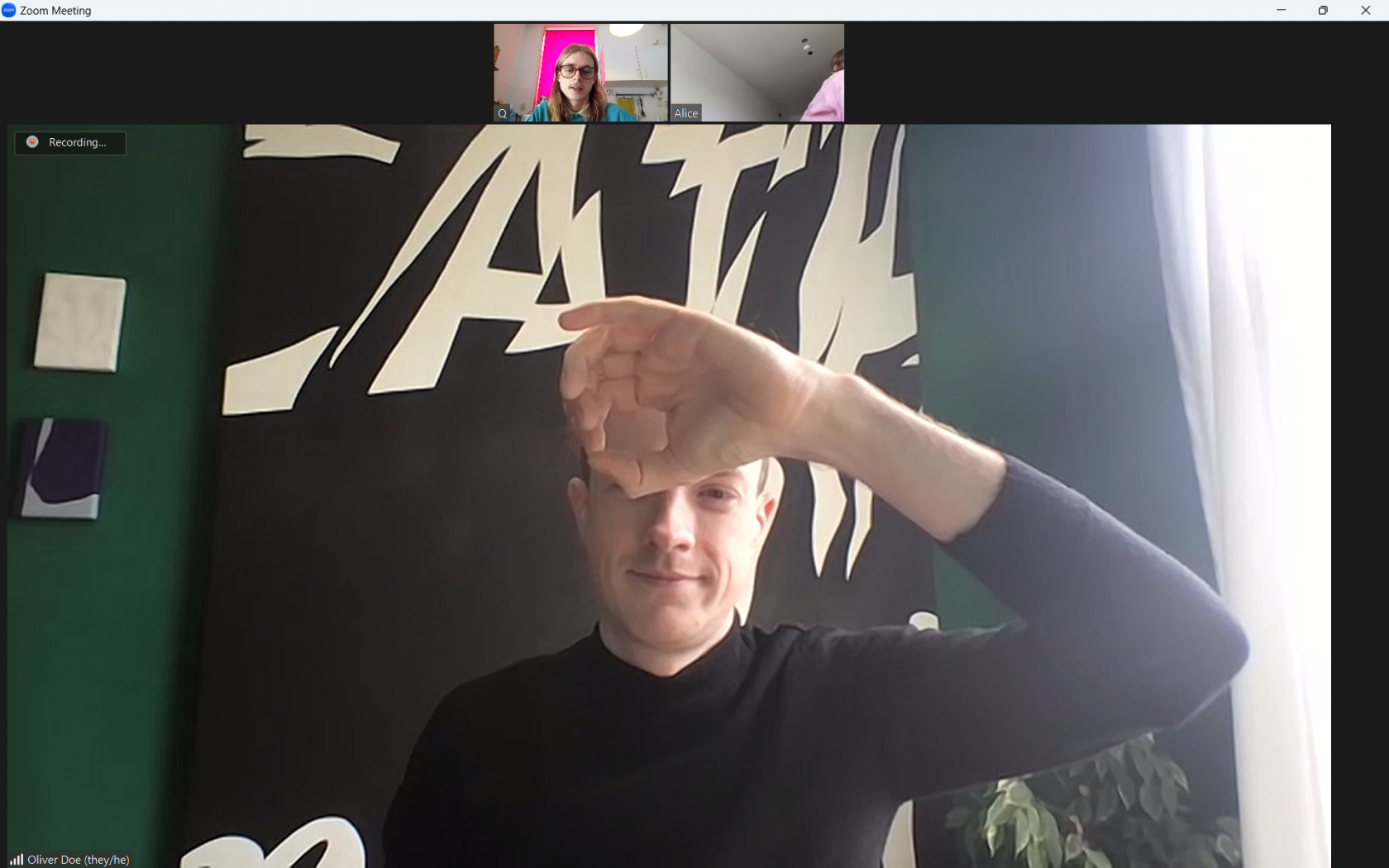

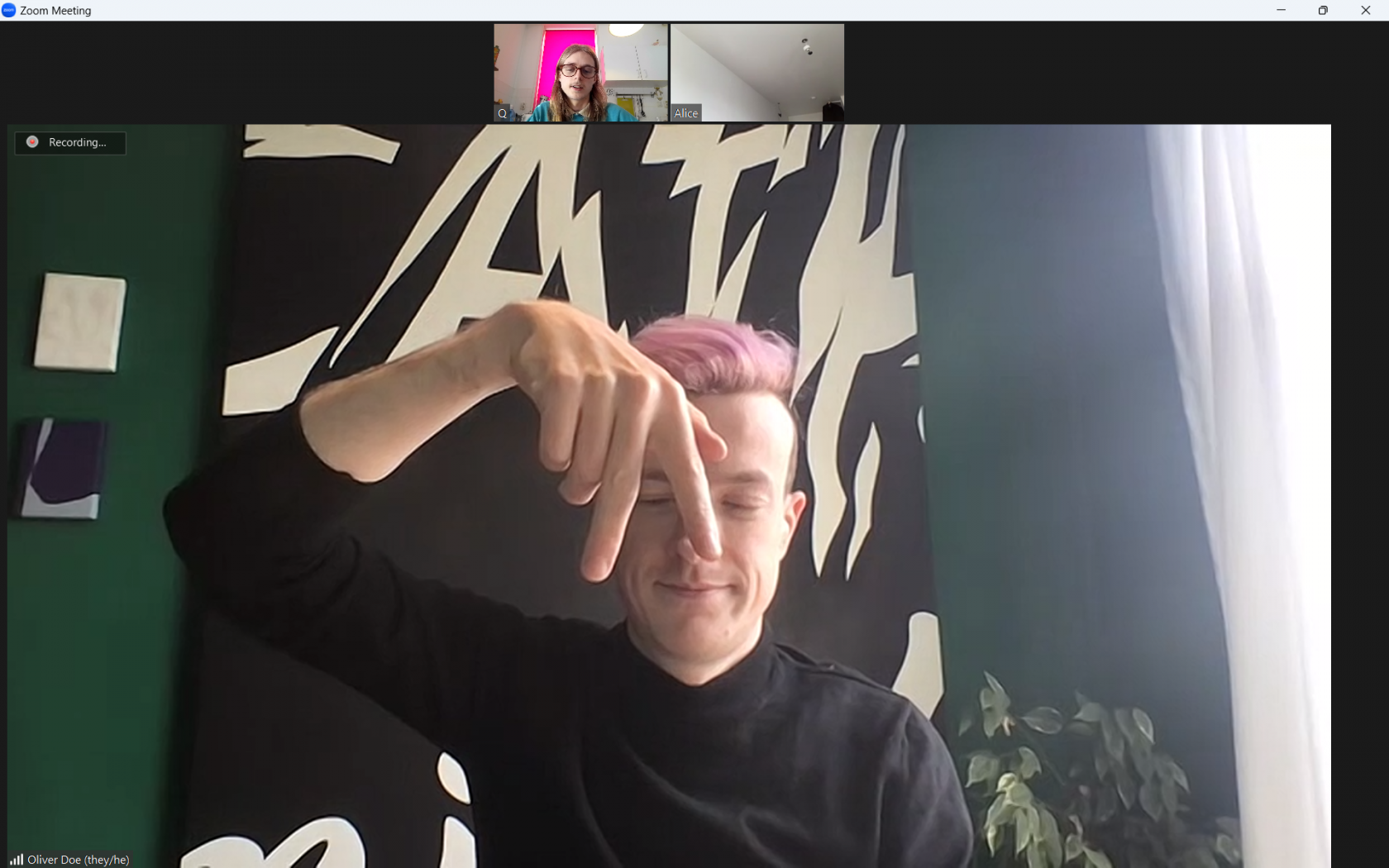

Last February, the exhibition Paper Cuts ran in SIGN+ Projectspace in Groningen. Our correspondent Michiel Teeuw invited participating artists Oliver Doe and Alice Slyngstad to reflect on queerness, language and body, in artistic practices and general society. What follows is a conversation based around different starting points: fragments of the exhibition, references selected by Teeuw and more general questions, each serving as prompts to think through the works.

0. Description of works

I enter SIGN Projectspace, one of Groningen’s spaces I most frequently visit. The exhibition Paper Cuts shows four artists, each dealing in their own way with language, writing, communication and codes in relation to identity and attitude.(1) In the building’s back space and basement are works by Ra’fat Ali and Mariana Jurado Rico. In the front space and the corridor, I find works by Oliver Doe and Alice Slyngstad.

In the middle of the space is a grey wooden block, with presumably two media players inside, linked to two projectors that are beaming in diametrically opposed directions onto what looks like 1080:1920 projection screens. The screens are both enveloped by silvery curtains placed in a gentle curve, and are both accompanied by a reasonably sized speaker on a pole. Through this setup, a video plays. I hear a voice, sometimes speaking, sometimes singing, sometimes also backed up by soundscape and music. On the screens, letters appear in what looks like Arial narrow. Sometimes the letters have a green mossy glow or a background visual. For a part of the video (loop) the text disappears and a double-exposure video is shown, featuring plants, heels, walking and the like.

Around this ellipse, several smaller and larger canvases have been placed on the wall. The canvases, all in a 1:2 ratio, vary from works smaller than an A4, to works larger than a meter in height. They are covered with duotone painting, consisting of brightly colored letters on brightly colored backgrounds. The letters, some of them serif, some of them cursive, some of them sans, are crumbled, stretched, layered, and sometimes only flirtily present at the canvas’ edge. All of this is executed in hard-edge, oil painting, and based on digital typographic renderings. In the space, there are two white wooden blocks, which perfectly hold space for two stacks of paper, each containing what seems to be poetry, performance scores or something in between. The texts are printed in low-contrast small type, in a font which looks like Times New Roman. At another moment, I find two performers, Oliver Doe themself and Daphnis Monastirioti, performing a sequence of movements and speaking a sequence of sentences.

f. queer

that’s tea.

so listen up diva’s,

we’re getting hunty here,

cause we’re about to serve slay,

and fierce it up.

for you!

— Katya

Michiel Teeuw: Alice and Oliver, thank you for joining me in this conversation. Both of your work seems to be engaged in an attempt to articulate a futurity of being through language – on a level of syntax, vocabulary, intonation and paratext, the textual aspect of your practices visibilizes a marginalized, everyday way of being in the world, loaded with alterity. To me, you also seem to share an implicit closeness to queerness as something that can happen and emerge through this kind of language. At the same time, “queer language” and the word queer have been co-opted, squeezed out, and emptied out to function as marketing terms in neoliberal circulation — which is focused on consumer identity. In this context, I’d like to ask both of you what queer means to you, and how you relate to queer language in your practice.

Oliver Doe: Queer, to me, is just my basic understanding of a way of being in the world which otherwise doesn’t make sense. That is obviously tangled up in a way that I identify with gender and sexuality, and the gender and sexuality of the people around me and the cultures I’m involved in. At the same time, I think Queer is a specific term or subculture: the political wing of the wider LGBT+ umbrella. As you said, the term Queer has been co-opted as a grouping term for LGBT+, without this sociopolitical meaning. That I find disturbing and disappointing, but it’s part of an inevitable cycle, and it’s not the first time it has happened. If you look at the beginnings of the use of Queer as a terminology in arts and academia in the eighties and early nineties, this cycle has already reproduced itself several times. But as it reproduces itself, it grows and grows – and now we’re at a point where Queer has hit this mass market, and not just the academic interior. So it’s a funny term to identify with, in this moment that we’re at. I don’t think it felt adequate for most people, but it’s what we have to work with at the moment.

In terms of my practice: the way I function as an artist, is to look at the way I look at the world. I look at the world through the lens of my identity, which for me circles around questions of gender and sexuality – circling back to what it means to make queer art or be a queer being in an unqueer world.

In terms of language: I’ve always been interested in language, but moving to the Netherlands, where I’m using my fourth language on a regular basis, what does it mean to then speak queerly in another tongue? I very much struggle to do so in Dutch. How do I look at the abstractions that are coming out of this, and how could this be translated into research that generates something vital – not just for me as an understanding, but for audiences as a mode of understanding me as a person and artist, as well as our queer subcultural world.

Alice Slyngstad: I am constantly confused by the word queer, I think. I don’t think so much about queer language, or queer when I work. My experience is that the word queer changes meaning in every context- and I find myself wondering what it means each time. I have a difficult relationship with the label queer as something that people are or not, as I’ve spent time in environments where this has been misused as a false gatekeeping premise- with queer to the fore, effectively silencing certain people in a group consisting of a variety of sexualities and gender identities, often based solely on anticipations from visual identity traits. This makes me really want to reject queer/non-queer binarisms, and fuels a constant searching for ways in which all bodies are queer.

Either way I’m interested in problems and compromises of language. One way that might come across in my work is probably as a rejection of singularity and singular voices, as my writing is scatological and fragmented but it also serves as platforms for a range of vocal exercises, voicing and weaving in interfaces, objects, users and desires.

e. body

MT: Recently, I have been thinking a lot about the role of the body in queer and other political art. This has been sparked in particular by the text Why I don’t Talk about the Body – A Polemic by Gordan Hall. The text talks about the kind of work we have all seen come into institutions: photographs and paintings of “different bodies”, but also the invitation of performance artists with othered bodies. Hall describes this as the Bodies As Evidence Curatorial Model, the Voguing In The Lobby Model, or The Spectacularly Naked Trans Performance Model, which then signifies artists as examples of their demographics, publicly displayed in an effort to signal the changing priorities of institutions that have been historically terrible at investing in the careers of female, non-white, and non-cisgender artists, while the artists’ bodies are expected to appear in the work functioning as a representation of an identity position.(2) This almost overlaps some of with Sarah Ahmed’s writings, where diversity is framed as a mechanism to uphold the whiteness of the institution, because the change only happens on the superficial level of marketing, PR, and visibility to the public. I would like to pose that your works challenge this notion of The Queer Body by [1] being in partial and non-spectacular visibility, and [2] focusing not on the body as a homogenous whole, but working with the tiniest of muscles and sensations. The performativity and description you bring forward seems to disrupt this kind of body-as-a-block. How do you relate to the phenomenon Hall described, and how do you see the role of bodies both in your practice and in these institutional contexts?

AS: Gordon objects to the term “the body” in that it implicitly sets up a binary between bodies and other capacities, qualities, or modes of experience. They claim that to speak of “the body” is to distinguish it from what it is not: “the soul,” “the spirit,” or, most commonly, “the mind”. In Goodie Bags I was writing from the intimate movements between digital interfaces and flesh, eyefloaters, silverfish, postures, messages, dreams, desires and identity development. The interface merges with the subject in the text, which is developing different measuring techniques for extrapolating bodily data in dialogue with online infrastructures.

OD: If we come back to ambiguity, I think of Alice’s use of ambiguity as a positive or constructive element within what we do. When you’re working that kind of process, a lot of things don’t make sense, and a lot of things only exist as questions without answers. In a lot of ways, it feels impossible to answer how I use the body as a positive space. But by rejecting the body or downplaying the role of the body in performance work, or Alice’s video, which describes very intimate bodily sensations and feelings.

It’s great to have Gordon Hall as a reference point: their practice is perhaps the first performance practice that I was able to identify with. And I couldn’t see it at the time, when I first found their work. I’ve never seen their performances in the flesh, but just looking at the documentation, I could see: Oh, Okay: this isn’t a way of performance that centers my body as a performer, or the bodies of the performers I work with; Because that’s not a mode of performance I’m comfortable with. I’m a very shy and anxious person, with this very blocky exterior, and I don’t like to put my body in the center of attention. And I think especially in queer performative circles,(3) that’s never about something that’s comfortable to me.

So when I come to make performance, it’s a way to use the body as a medium without centering what the body is in the room. Which is why the mode of address that happens in the performances is dropped right down to the most basic level. There’s very little intonation in what is said – and when it is there, it’s very subtle, marked, deliberate. But it doesn’t often escape into this outrageous or spectacular level. I don’t want to situate myself in that. As you mentioned, I don’t think it’s constructively comfortable for audiences either. In a way, I think it’s sort of eating away at the economy of what queer artists are in institutions and galleries – and how we are meant to see our own bodies.

To look at painting: If I think about what queer painting is, it’s these slightly splashy and slightly abstract figurative paintings of slightly butchy gay white men. And I love some of them, but they don’t agree with what my reading of queer is – and I don’t think they have anything to add to the contextual canon. Which is, like in the performances, I ignore that way of working and go for the flattest thing possible.

Flattening everything, putting it on the most basic level, that decenters what the body, the language and the phrasings are – to the point where none of it actually really matters. Formulating something embodied from this ambiguity, into something performative, without becoming spectacular, is tricky: because how do you relate to the audience?

AS: The work I’m showing centers around the audience as a performer, which is something I’ve been working more with later and earlier. In this work, there’s an extreme binary: you can either watch one screen or the other, because they’re faced opposite of each other. You look for changes, or you have to look for material, but in the end they’re quite similar. They’re more or less a mirror, but sometimes it’s activated like a conversation.

OD: The installation kind of becomes a monolithic body on a stage, and that body is doing the performing of the installation; it has a voice and that voice is visualized on the screen in text. The body is still present in this ambiguous queer way: what is a body, is it a monolithic rectangle? What does it mean to have a voice and to speak? That is something I could identify and recognize, as a material aspect of being present without being spectacular.

(2) Gordon Hall, Why I Don’t Talk About ‘The Body’: A Polemic, Monday Journal vol. 4

(3) OD: I say performative circles not just as performance art in the galleries, but the general performativity of queer being as I’ve known it in the past ten years.

d. cypher

We have seen that the person posing the riddle finds himself in possession of knowledge – he knows. On the other hand, the guesser, in guessing, shows that he also knows, that he is the riddler’s equal. Thus, to set the riddle is above all to test the guesser, to investigate his equality. The question also includes a compulsion. Taken as a whole, then, from the riddler’s point of view the riddle is both a test of the guesser’s equality and a matter of forcing the guesser to demonstrate his equality. Here I need only recall the concept of the exam. It is obvious that this test and compulsion are not intended for random persons at random times: the tester must have a reason for testing and compelling, the person tested must have a reason for submitting to the test and to the compulsion. From this we can conclude that the sole or true point of the riddle is not the solution itself, but rather the act of solving. The answer was already known to the riddler, thus for him it is not a question of learning it again; what matters to him is whether the guesser is capable of giving the answer – whether he can be made to supply it to the riddler.

— André Jolles, Simple Forms

When reading this fragment from André Jolles, I had to think of the specific forms of queer code you use in your work. Jolles describes here not the solution being important when you are asked a riddle, but the solving itself. I had to think about asking if someone is a friend of Dorothy’s to check if they are gay. Later, Jolles describes group jargon and using a riddle to see if someone belongs in a group. From here, I was thinking if a riddle can be a keyhole, through which the fractioned image of a community shines through, but which needs a key (the act of solving) to be opened?

OD: My basic methodology really consists of fucking with that principle. There are these codes which act as keys, entry points into a community – both positive and negative. You go to the bar and the doorman will ask, Have you been here before?, not because he’s interested whether you’ve entered that space before. Even if you haven’t, you know what the space is designated to be, as a queer space. It’s a way of testing that knowledge.

I remember the first time I encountered that test. I didn’t have the key, so I didn’t know what the answer was meant to be; that it wasn’t an actual question that served a specific purpose. I was standing in the queue with someone else, and said: Oh, I haven’t, but he’s been here before. Oh, okay! It’s this funny thing in which you don’t realize until later what you’re actually being asked. An argument could be made that this is present in general queer ontology, where we don’t know what we’re being asked so much of the time, because our way of being is not designed to fit within the boundaries of the expectations of the questions of the normative world.

There are codes, types of languages and phrasings, like the use of polari, kaliardá in Greek, these kinds of sublanguages. There are sublanguages within those, and coded parts within those. Sometimes I find it really interesting to mix those up. So I find it really interesting to find a numerical code that would have been used in 1940’s Britain, with a reference to contemporary drag speech – which comes out of Drag Race US. There’s an absolute temporal clash between these two, which are not overlapping in time, space or meaning. What happens if those answers are posed at the same time? What frame of reference are you giving and taking away from people? Where is the keyhole in the first place? Do we imagine it to exist?

I don’t think what I’m presenting is a question that has any answer, but rather a mode of ciphering different parts of these codes out, mashing them together- it is unanswerable. The way I identify with queerness is this temporally abstract mode of being that is constantly in flux. I don’t understand this gen-z way of being queer anymore, it’s that quick! That’s why I find it funny that a lot of my work is based on historical research – which brings a friction. Part of me doesn’t want to fix that problem, wants it to remain abstract. I use drag race as a reference point, but I didn’t start watching it until maybe two years ago. I still don’t watch it as a form of entertainment. Am I doing research, should I be taking notes then? Fracturing the keyhole rather than building one into the door. I wonder if that door exists – maybe it’s a barn door where the top half opens. There are different barriers and types of doors which change all the time.

AS: For me, the cypheredness is a natural consequence of writing in a fragmented way. You’re either trying to decipher, or going with the flow of fragmentedness and scatteredness – or a constant in between, like I find myself in a lot of times. I have this very short-term and scattered focus, which I’m actively using when I’m writing, generating this fragmentedness. Very long, big jumps.

MT: It also made me think of Margaret Price’s description of Crip Theory: privileg[ing] the dis-composed, the contingent, and the mobile; in McRuer’s phrase, it “keeps on turning”.(4) Discomposition could also be a synonym for being fragmented, or not fully composed or fully straightened, as a mode of textuality?

AS: I think it’s the most basic and general mode of being in the world today through impossibly short attention spans, in that sense fragmented is becoming the norm.

(4) Margaret Price, The Bodymind Problem and the Possibilities of Pain

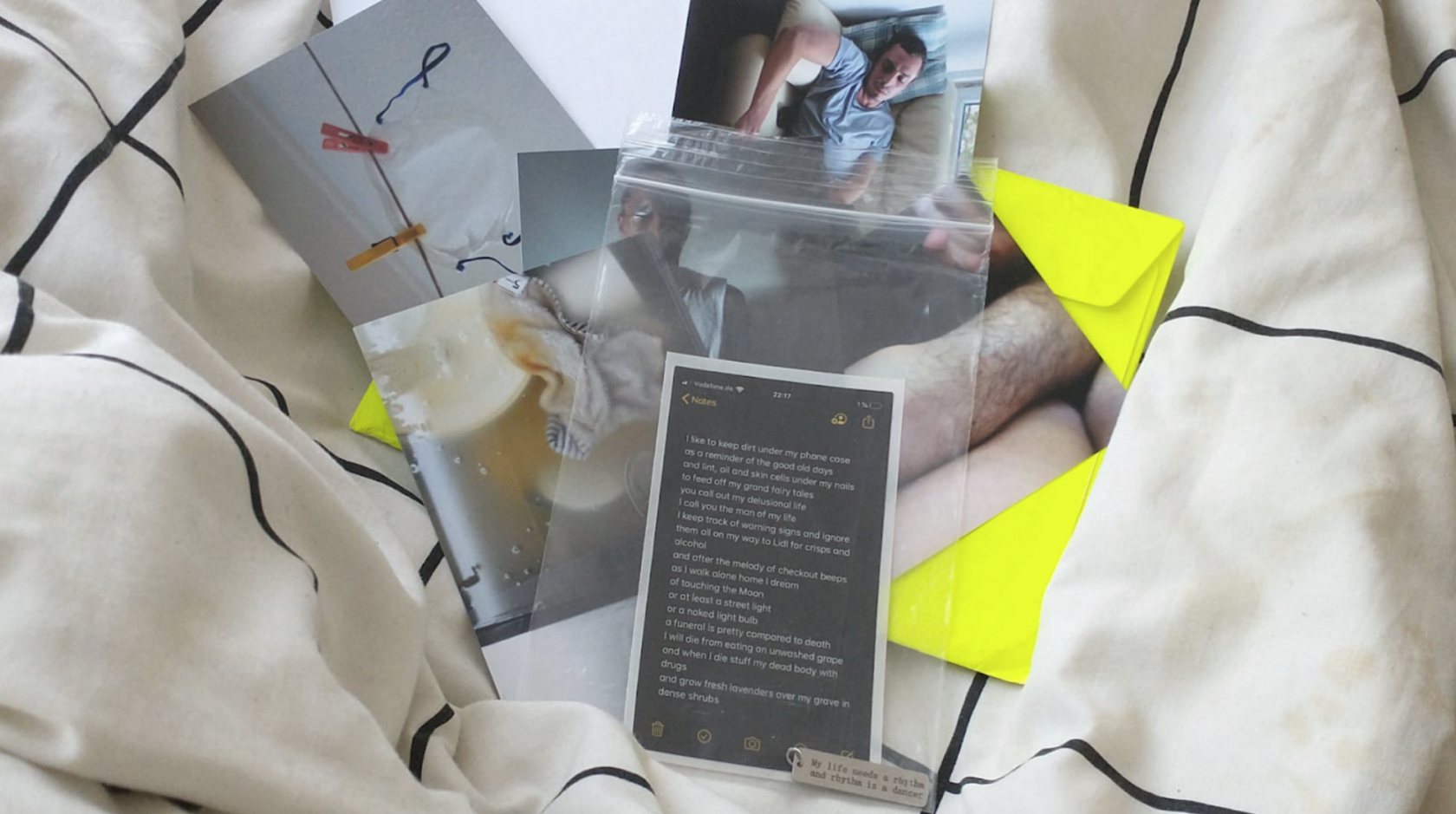

c. interface

MT: Alice, I was flipping through my collection, and I found back this mail artwork by David Lindert. Somehow the first sentence, I like to keep dirt under my phone case, and the similarly daily pictures reminded me of your practice. Simultaneously, they touch on a topic present in both of your practices: the way texts appear on surfaces. Could you both share a bit on how your work is affected by reading books, scrolling, chatting, writing, et cetera?

AS: It’s a beautiful text. This is also how I write in this exact scenery, notes. And it becomes very intimate since it’s on your phone and in between the dirt of your fingernails and your drooling face at night, between all your social situations, active all the time. In my last works I’ve been writing from these interfaces like Google Maps, Grindr, Tinder, Feeld. For Goodie Bags, the entrance point was this shopping app called Vinted, which was presented to me during the pandemic. I had recently gotten a big salary from a commission, and when I found this website I thought it’s such an amazing way to look at these affordable second-hand clothes at home. I decided to allow myself to only do that for three weeks, and nothing else. The work Goodie Bags is a letter from this period. With the lockdown and the curfew, my social interactions were limited to going to this pickup point from the shipping company that Vinted made. It brings the possibility of circulating second-hand clothing and circulating bodily information. There is so much information in clothes, from body-to-body-to-body. There’s so much small gestures in how an item is wrapped from a sender. Sometimes they leave a little perfume sample, or the detergent something is washed with has a very distinctive smell. I myself am allergic to perfume, so I’m very sensitive to this. With the focus of just doing this as a full time job, being in bed, swiping and scrolling these interfaces for three weeks, it made for a bit of a bizarre situation. For me, it was the first time I felt like I could dress how I wanted. I could order clothes and would finally figure out my sizes, like my french dress size. Cause I’ve never been comfortable with trying on clothes in shops, where there’s so many layers of seeing and being seen. Isolating that by ordering things to my home was an extreme relief, which is why I took on this extremely vulgar project of only shopping for three weeks. It was real retail therapy. After the first day, I decided I would only go out of the house wearing these clothes. wearing what I buy when I pick up new things. I had to present myself with the identity that I picked up. The work is a collection of these narratives.

I see the silver fish reappearing throughout the work as another kind of body, who’s surfing and navigating, and feasting off of my remains, my bodily abject; As I collect more and more packages, the cardboard boxes became a silverfish explosion. Who knows they like paper?

MT: I thought it was about grindr!!

AS: The labor I’m doing while working on these interfaces is the same. We build ways of collecting information, and the way information is structured is also powered towards collecting information in this infrastructure. The last few years I’ve been talking about Grindr and other dating apps as my job, and my friends would ask me how work is going. It’s never about finding something, it’s more about being so amused by everything on this entertainment channel and being addicted to extrapolated all this information. There is a lot of extrapolation in this. Like on Vinted, if you don’t know your own size, you have to find your own ways to extrapolate information. It does relate to the size of your actual body.

OD: You mentioned this hierarchy of information that research is supposed to be based on. I think where I am as a researcher is very much based on that hierarchy. I’m a massive nerd and I love reading journal articles, and finding things written in the seventies. I prefer that anachronistic way of working, and that scientific lens on what’s happening now. I would rather read a journal article or visit a conference about what’s happening on Grindr, than sit through it myself. I’m giving myself this personal distance but there’s also the guilt that comes with that: I’m not fully engaged with the process on a personal level and this is something I’m still figuring out. Because I’m working with anachronistic and transtemporal processes anyway, it doesn’t become a problem for me. I’m not mining the information myself – I’m just taking what’s there and reconfiguring it in all the wrong ways. My work is not designed to be intimate in the way the language from a dating app might be, or designed to be a mode of communication like Polari might have been in the 1950’s. It’s meant to be all of these things, all at once, put it on a bagel. The way we are asked to consume media so much of the time now actually plays a way into what I’m doing. Instead of social media, older books and music in particular are where I’m getting things. The text I’m showing both references Perfume Genius and Grace Jones, as well as completely made up reference points. The texts I made are reconfigurations of all of these references. Adding the fake reference points generates the abstract queer language for me, where nothing is really real anymore. What’s actually being communicated? It has to come with this point of facing myself with this text or media from every angle, all at once.

AS: For the work Goodie Bags I was mostly working with language that was shaping the space for me to be within the three week shopping period. So I was mostly including language like messages / profile texts that were shaping that space slightly. Someone sent me this amazing message on Grindr, and I was astonished that after I said hi they wrote this personalised fantasy novel. I thought that now I had the birthday gifts and christmas gifts to all my friends for years cause this message had everything. It was in Norwegian, so it might not translate that well, but I’ll give it a try to share it:

It had these absurd timings: it went from a “Hi, how’s it going” to this little situation. I’ve imagined this situation a million times, because it’s just so peculiar. Filling a glass with beer, one on top of the other. What’s your bodily posture while you’re doing the cheers? I keep applying the dramaturgy of this message to everything in life.

But there is no personal trace of this person left; I never work with material that could infringe on someone’s right to privacy.

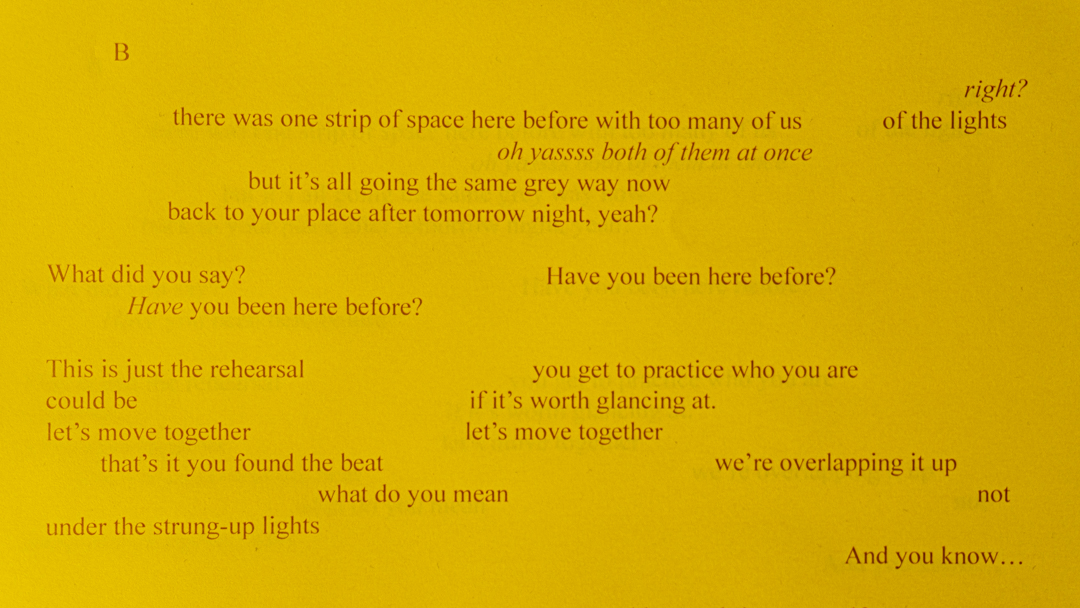

b. B

OD:

B

right?

there was one strip of space here before with too many of us of the lights

oh yassss both of them at once

AS:

laundromats

unlike girls who don’t

B

it’s flawless silk

MT: While browsing the space at SIGN+, I noticed both of your works had a capital B, kind of thrown in there.

I think of this kind of interjection as a post-internet gesture, related to the 🅱️ Negative Squared Latin Capital Letter B Emoji, popularized through black twitter I believe. At the same time, I have a feeling that it operates in very different ways in both of your practices. Could you share something on your use of this letter?

OD: What the little segment you’ve taken there misses, is actually the line before. So it’s kind of funny, where I deliberately took the B out of context from the line before. And it’s also this part that’s very much knitted with the other paper. This fragment really collides 3-4 reference points all at once.

I normally don’t like giving away where these points come from, but I’ve almost given all of them away in the interview so far; The letter coding is based on this Grace Jones reference, but if you tie in this other piece of paper and see how it overlaps, then it’s a Perfume Genius reference. The way the Grace Jones reference is coded in is a sort of alphanumerical code of just using letters, which was common in the 50s and 60s and appears in David Hockney’s early paintings, becoming this (queer) art world reference; and then there is this drag race reference as well. It’s interesting to see this section cropped without the other half of the same work. At SIGN or other exhibitions where I showed this split text-work, visitors often take one of the two pages or just look at the page. These are often double-sided prints, so you might miss half of what’s going on. In terms of the B, it was separated from the rest of the Grace Jones reference [Pull up to my bumper, baby], because that 2nd B is acting as the vocative, it is the call, the interpolation if we’re going down the Judith Butler route, of baby, to put baby in this thing: Is that the right mood up here? To sample that in with this anachronistic mode of coding, being able to just tie on Perfume Genius to the end of Grace Jones – which absolutely makes sense to me as this trans-historical leap, right? That’s when you’re able to do something with the language directly.

AS: I relate to the same non-specific but very specific use of the letter. I think my B is a formatting error that has been left behind, or put to the fore in my text. I like working with lists, and in making this text I worked with a numbered list because I was curious how it’d affect the reading of this text. If you make a second bullet point, then the number becomes a. & b. (?), the typesetter I was working with, she also decided to emphasize the B. It’s used as babe, or bro. Most of the text is navigating trans-femininity; trying that identity, trying it on. I’ve been working with the word “burl”, do you know what a burl is? It’s a knot on a tree, that is often used for specific woodworks. I like the sound of the word, burl, boy-gurl, burl, it has a bit of a casual sound to it. It also sounds like the word pearl; I’ve used it quite often before, not as a gender-neutral but as an alternative.

~ ~ ~ END ~ ~ ~

The exhibition Paper Cuts ran 5 February – 5 March 2023 at SIGN+ Projectspace, Winschoterkade 10 in Groningen.