Stroom Invest interview / artist Jiajia Qi

Art has a reputation for being elusive and hard to grasp at the best of times. Our conception of what art means to us changes throughout times and across cultures, and spans a vast spectrum of wildly different practices concerning everything one can imagine. It also has the capacity to expose how different cultures think very differently about fundamental concepts such as time and space. Jiajia Qi’s diverse background and artistic practice has taken her all across the globe and she has approached the subject of time and space from a plurality of ways.

Can you tell us something about your background?

“Originally I studied Sociology at the University of Zhejiang in China, after which I travelled for two years before I stayed in New Zealand for one-and-a-half years, not really knowing what I wanted to do. During that time I decided that I wanted to study art or philosophy because I wanted to understand how I perceive my surroundings and my perspective on it. I decided to study Interactive Media Design at the Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague (KABK), the Netherlands because I wanted something to study more than just art.

During my studies I realised that the most interesting thing to understand is actually to understand yourself and the space that surrounds. As someone from a Chinese background studying art in the Netherlands it was hard to understand my new surroundings. Which isn’t about mastering the English language, but it is about understanding the way that people around you are thinking. As a foreign student you need to understand how Dutch academic students function and how they think in order to become part of the group. Many times you don’t know what is precisely happening and there will be a gap in understanding. I think this is one of the things I am looking for in my art. Even though the whole world is getting more similar to one another, there are many small differences that are hard to get around. There are small differences in the way that people from East Asia understand the concept of space compared to the way Europeans do. Because these differences are small, we easily accept the distinction between the two, yet we find it hard to articulate what these differences are. Unlike the Western sense of space, which tends to be fragmented into small pieces, the sense of space in the East-Asian utilises empty space by performing activities within an unseen boundary, it is viewed as a verb rather than a noun. During my study at KABK I did an exchange in Japan where I studied architecture and also did a formal tea ceremony training while I was there. The Japanese have a very special concept called “Ma” and it relates to all aspects of life. It is a pause in time, an interval or emptiness in space. It is the space between the edges, between the beginning and the end, the space and time in which we experience life. The silence between the notes that make the music. The tea ceremony is a good way to learn to understand this. The ritual is all about being in the moment and allowing time to appreciate it. Within the ceremony you even talk about that very thing.”

What kind of role does philosophy have in your work?

“Philosophy for me is about finding your own language and about understanding your surroundings. Currently, Deleuze is very important to me. He always talks about the horizon, about becoming and about continuing to be, which is related to the Japanese concept of Ma. But Deleuze’s language isn’t always clear to me. To me, the way he talks is like a rice cake. When you have a bit of rice cake in your hand, it is a bit wet, a bit sticky and you can’t ever tell what shape it really is. There is something there, but you don’t quite know what it is. My artistic work is pretty much the same and I like to think about it in that way. I am doing research about the blank space, which is something that we don’t have a standard principle for to recognize what it is. A large part of my practice is also theoretical research and in my research paper I am comparing Kafka – Toward a Minor Literature by Deleuze and Guattari to the book Architectural Body by the American-Japan based artists/architects/poets duo Shusaku Arakawa and Madeline Gins, in order to investigate how both initiatives aim to invent a new set of guideline reckoning with the unknown, through creating their own architectural form that goes against daily habits.

In my research paper about this, I concluded how exploring the boundary of blank spaces enables one to avoid becoming trapped in ‘common sense’, and to raise the question of when individuals seek a reality beyond reality, how many of the truths they perceive are influenced by their familiar social-historical context? This research paper was titled No Where, Now Here and was presented online at AGxKansai 2022 “Art and Philosophy in the 22nd century After ARAKAWA + GINS” at the Kyoto University of the Arts, Kyoto, Japan.”

How does all of this relate to your artistic production?

“My art, more or less, is concerned with what is absent, rather than with ‘what it is’. I am interested in turning the familiar surroundings into something unfamiliar by precisely measuring, calculating and placing a given spatial setting. What I am searching for in my work is not about following, figuring, or defining, rather, it is about how to continue gazing, measuring and modulating. Just like Deleuze’s writing, my work has no recognizable outlines and I want to stimulate viewers to compare what their surroundings offer up for observation and what they actually observe.”

What is an example of work you have done since you have gotten the Stroom Invest Grant?

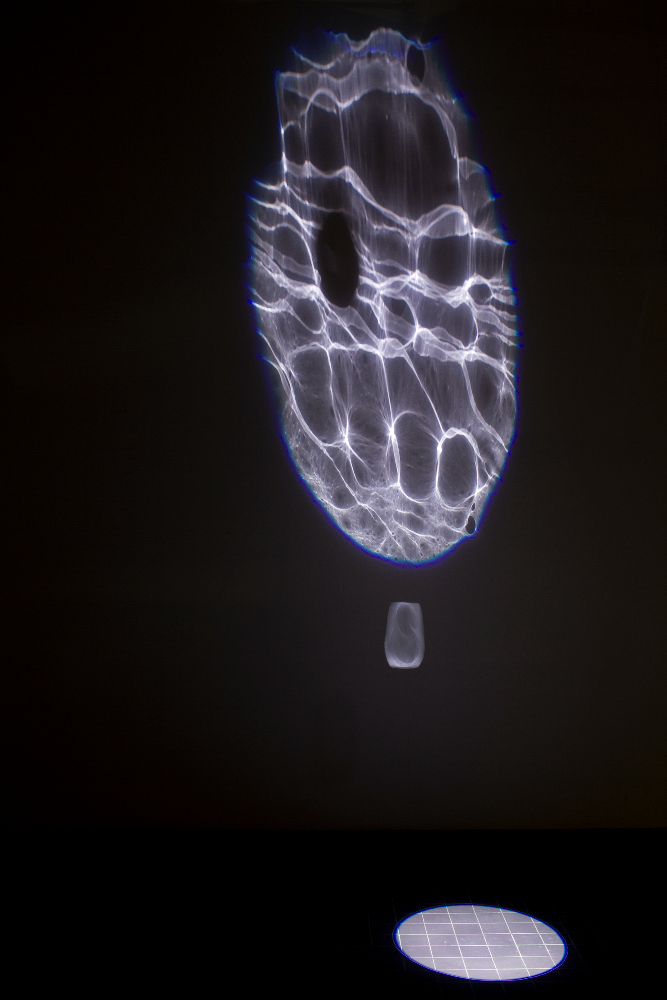

“One of the things I have produced is a site-specific installation titled Somewhere Else, Anywhere, But Here for the Billytown Gallery in The Hague, which is present as part of the exhibition- RSVP from January 28 to March 19, 2022. I invited Fumi Takenouch, a Kyoto based architect-performer-visual artist, to join me in presenting her piece titled Scoot. We were originally scheduled to collaborate on a performance piece in Kyoto as part of my original plans for my trip to Japan in 2021. However, we have shifted our expectations, creating each

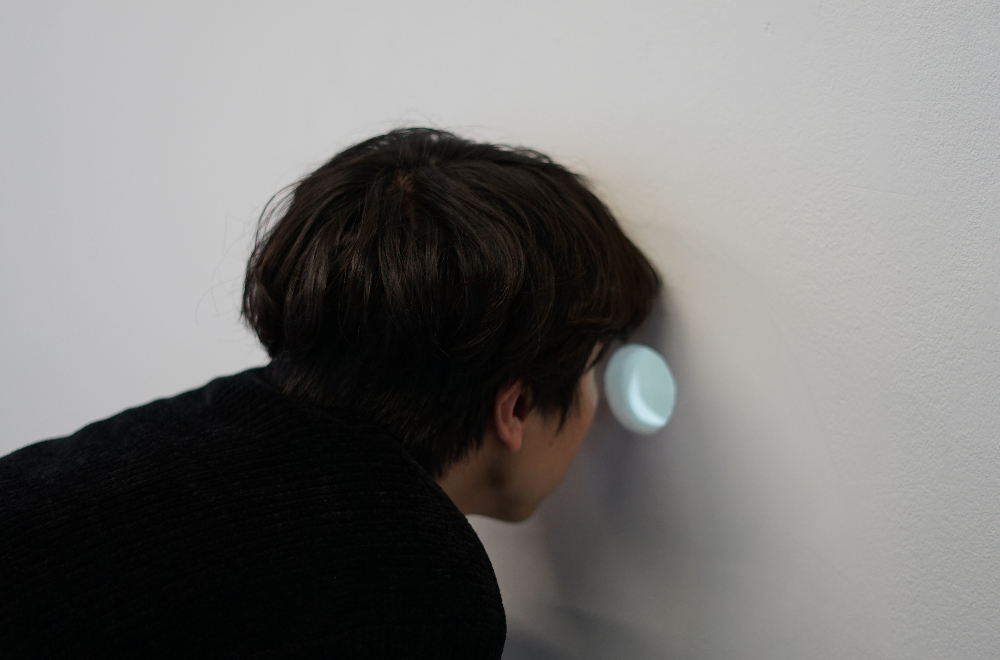

work independently, with the goal of examining the link between physical and mental space through body gestures. As a result, we grouped them together to allow for the development of their own dialogues and interactions. This also functioned as a dress rehearsal for our near future collaboration. In Somewhere Else, Anywhere, But Here, I transform a concealed storage room within the Billytown gallery into an installation component for this project. This room becomes a closed space visible only through two peepholes. One is adjacent to Fumi’s film (on the front of the exhibition wall), allowing viewers to see part of the installation’s static aspect; the other one is on the side of the exhibition wall, inviting viewers to see the moving moment of the installation.

Observing something through a peephole is a paradoxical feeling that mixes distance and intimacy. The body movement underlines that viewers are observing something entirely for themselves, they are simultaneously being witnessed by the general public. It is exposed to a moment that people-yet-to-come who in some sense are already here, and their physical and mental being disrupted, detached, and dislocated. To then refers to a situation in which reality rushes in as an additional reality to cover the original reality, a complexity within rather than one of beyond. As a result, viewers have only been aware that “something” is present but unable to articulate “what” is here.”

How do you structure your artistic practice?

“After graduating in 2018 from KABK I have been doing different residencies between Europe and Asia. At the time I didn’t have a studio but I was always working site specific. I like to try and understand how different surroundings have an impact. Residencies are great because they are always site-specific and provide you with a context to work in. You are working and residing in the space and you can analyse what happens when you put something in it. Many times you read about a place and when you are there it is a totally different experience from what you imagined. It’s almost like some sentences in art theory, sometimes you don’t get it, but when you are there in the situation, you understand it better.

This way of using residencies in different countries worked well until the pandemic happened and I couldn’t travel as easily. I still did four artist residencies; two in the Netherlands: Billytown in Den Haag and Stichting het Wilde Weten in Rotterdam, and two residencies aboard: Gornji Grad Residency in Slovenia and Kontempora Residency in Bulgaria. Ever since I have a studio which changes the way I make things. In a studio you have your own space, which is a more stable context. It allowed me to observe the repetition and progress during my project development. For example, the effect of time and weather conditions affect how my installation is perceived. Currently I am working on making a machine that with a mechanical rhythm reflects light. I try out my installations in the studio and can observe how changes in the daylight and artificial light affect the materials. Living with the art pieces made me understand them better.”

Stroom Invest Week is an annual 4-day program for artists who were granted the PRO Invest subsidy. This subsidy supports young artists based in The Hague to develop their artistic practice so that artists and graduates of the art academy can continue to live and work in The Hague. To give the artists extra incentive, Stroom organises this week consisting of studio visits, presentations and several informal meetings. The intent is to broaden the visibility of artists from The Hague through future exhibitions, presentations and exchange programs. Stroom Invest Week 2022 will take place from 7 to 10th of June.