Artists in the Periphery: Florence Wild in Stockholm

In a time of pandemics and social isolation, we are starting to question the way in which our world is constructed. Digital technologies make it possible for a large number of jobs to be performed from home or from wherever you want. Which begs the question; does it really matter anymore where you decide to locate yourself as an artist? Through this new series of interviews with artists located all over the world we are going to explore artistic practices which place themselves in the periphery of the art world. This time with Florence Wild in Stockholm.

Florence Wild is an artist originally from Auckland, New Zealand, who moved to Sweden in 2010 and is currently based in Stockholm. She graduated with an MFA from Konstfack University of Arts, Craft and Design, Stockholm, in 2017. Since she has been working on developing her studio-based practice alongside part time work as an education administrator and a library assistant. In her artistic practice she works with mostly humble or found materials exploring ideas around time, observation, labour, nurture and archives. She has exhibited throughout Sweden in numerous group shows, as well as in New Zealand and other places around the world.

How did you end up moving all the way from New Zealand to Sweden?

“I did my BFA in Auckland and graduated in 2008, after which I moved to Sweden in 2010. Which was neither for art nor to study, but for a guy. When I graduated with my BFA at the age of 21, I didn’t consider myself to be an artist and I didn’t feel professionalised. I was having exhibitions but I did not equate that to money or career. Perhaps I didn’t really have time to reflect on that before I left New Zealand.”

Did you immediately enroll into an MFA program or what did you do during the first couple of years?

“Before being accepted to the MFA program at Konstfack I lived in Malmö but I didn’t do much art at all during that time. It was a period in which I was outside of either context; I was no longer part of New Zealand, but I was also outside of the Swedish context and their “ecosystem”. It was hard to establish myself in Malmö. A friend from New Zealand ended up doing her MFA at Malmö Art Academy and through her I met a number of students studying there. Funnily, my flat became a place where exchange students from art school lived, which in hindsight is an apt metaphor for how I found myself in Malmö in some ways.”

Art schools are usually a gateway into the art world, but how important are they for the art scene in Stockholm and in Sweden?

“Art schools in Sweden feel very much like an incubator for the entire art ecosystem, and Stockholm is like a more condensed version of that as the epicentre of Sweden’s art world. With a system of preparatory art schools and limited spaces in the programmes they are offering, there is a seriousness and a professionalization apparent that, as a student, I found both intimidating and vaguely amusing. But it became obvious to me that admittance to an art school was the first rung of the career ladder.

When it comes to Stockholm there are two main art schools; Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design; and the Royal Institute of Art. There is a high level of competition and comparison between the schools and their education systems, as well as between the students who attend them and the annual degree shows. It is not uncommon that even first year group shows get attention from online art platforms, rather this being reserved for the solo shows by final year students. To me this underscores the encroachment of the commercial art sector into arts education. It is stripping young artists of an environment for mistakes, risk-taking and experimentation.

My work as an administrator also gives me this fascinating insight into the Swedish art education system, being exposed to the machinations that produce the education I myself have been a recipient of. I think what the students get here for their education is pretty incredible; student kitchens; 24/7 access to studios and well equipped workshops. It is a luxury that enables a level of dedication as a student, but it also creates almost a false sense of security. I watch the ambitious works of students take form at the school and wonder if the works could also be made outside of the institution.”

And how has your experience been as a graduate from one of these very institutions?

“As a recent graduate, I experience Stockholm as very much centered around institutions in general, and that the understood goal is to emerge into their realm. Onus is put on the individual to monetize the knowledge the art institution has imparted. Your identity as an artist is formed through your passage through the art schools, the funding bodies, the residencies, the awards and stipendiums. It can feel like obtaining grants, besides providing recognition and signifying quality, are seen here as accepted strategies to sustaining an artistic practice. There is a large amount of support available for artists, perhaps more than in other countries, and they are also relatively accessible. But this creates a strong adjacent artistic practice of application writing, where an artist’s ability to write around their practice has grown in importance. I have this ongoing work on my website, “attempts at artist statements”, where I collect my efforts to describe my practice in applications. I am interested in the absurdity of this whole machine, as I try to move further into the ecosystem of the art world and up on the food chain. It is a way to illustrate the hours spent crafting endless applications that usually bear little fruit.

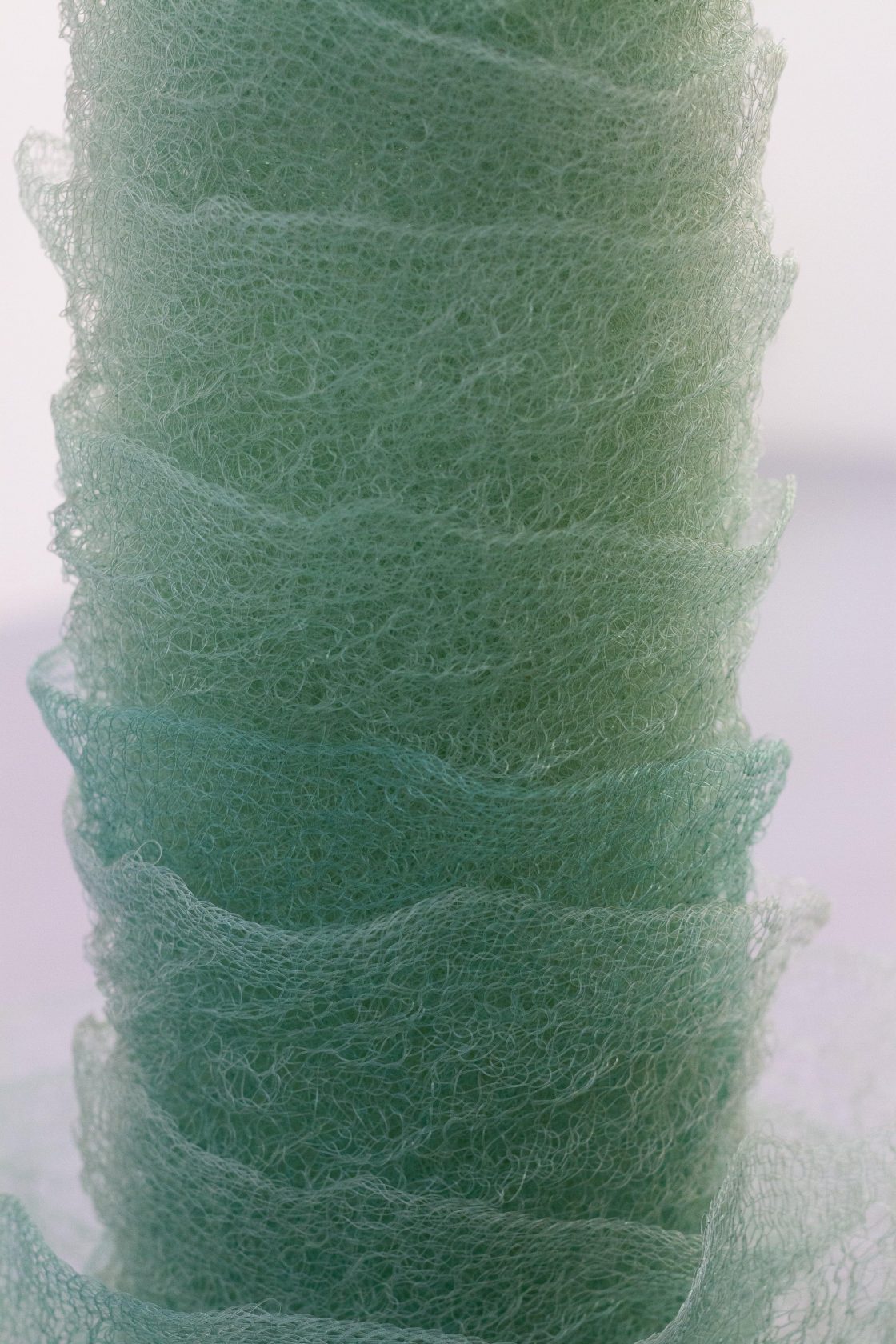

Ever since my graduation in 2017 I have been working peripherally as an artist in Stockholm. When you work in the periphery it means that one’s various other jobs and responsibilities are in constant battle with one’s practice, which is usually a mixture of choice and circumstance. I have felt the need to find a situation through which I can remain as self-sufficient as possible and sustain my practice long term. At the moment I have a part-time job as an education administrator/library assistant at Konstfack’s Fine Art department, which is a necessity to support myself. In some ways I still have difficulty seeing my practice as a profession, or commercially viable. I wonder if I try to subconsciously sabotage such tendencies within my artistic practice by working on these really time-consuming pieces, like my hand-knitted fishing line works that take many years to complete and that I then keep on reusing in new works… I work a lot with repeated gestures, such as the knitted stitch, to talk about time, relocation, and labour. It becomes increasingly impossible to separate things out into quantifiable items.

I think about the life of a practice and my role as artist to nurture, maintain and sustain it. For me, remaining peripheral could be a strategy of prolongment, a biding of time. Right now at least, in a restricted environment, I am just trying to remain as productive as possible and accept that my other responsibilities (as an administrator for example) may take priority. The scale, or act, of exhibiting has for example, been of less importance in 2020.”

Sweden has been in the news globally many times during the pandemic because of its alternative approach to the situation, which also made me curious to know whether or not the same has been true for the art scene? What has the attitude been during the rise of the pandemic?

“At the beginning of the pandemic there was an underlying tone that art and artists could lead the way in adapting to our new conditions. To refocus on the local, the temporary, to encourage exploration, a seeking out of sorts. In Stockholm there were a number of exhibitions organised outside; Tyst vår (Silent Spring) in a forest area of Stockholm’s Royal National City Park and Offspring, a group show in the southwestern forest reserve Sätraskogen. I was part of a couple of really enjoyable local initiatives, such as Open Window. This was organized by the artist group Hjorten, consisting of Nikki Fager Myrholm and Maria Toll, which saw artists install works in their windows and balconies. The inspiration for this was drawn from similar events in Berlin and Bergen. I also took part in the show Il Giardino, which was curated by artist Giulia Cairone in a garden in Stockholm and then documented and distributed through the artist run gallery Galleri Nos instagram account.

Exhibitions in forests, gardens and urban green areas feels logical here, and I thought maybe that had something to do with the Swedish relationship to nature as an essential part of everyday life. This is perhaps best illustrated through something called Allemansrätten; the freedom or right to roam, which is granted by the Constitution of Sweden. It gives everyone the right to access nature and wilderness, with the philosophy of do not disturb, do not destroy. Everyone can freely wander, cycle, ski, swim, pick mushrooms and berries, and camp on any land that is not cultivated, close to a private dwelling or a private garden. This mentality gives an openness to the potential uses of the outdoors as sites for temporary, considerate exhibition making, and Stockholm has a real abundance of green spaces.

It will be really interesting to see if this exhibition format will re-emerge once the weather gets warmer; that it is embraced as part of a natural reorientation with how we interact with the world around us. It feels more relatable, and is the literal opposite of the white cube, which feels more and more to me like a resistance, or amputation, from the rest of the world.

It allows for a blurring between the central and the peripheral, where art takes place in a landscape peripheral to the art world but central to a person’s immediate environment, daily life and wellbeing. Most smaller galleries have also remained open in some physical capacity, which has been greatly appreciated and so vital to the survival of art and culture in a climate where it is seen as ‘unessential’.”

One other thing that Sweden is somewhat known for is its eagerness for an early adaptation of digital technologies. What we have seen a lot in the Netherlands was an explosion of online collectives, platforms and initiatives. Have you seen similar tendencies in Sweden?

“I was amazed by the resourcefulness and acceptance by galleries and museums to transition to digital spheres. Sweden is pretty well known for fully committing to digital alternatives (I don’t remember the last time I handled cash for example), and the art world in the time of Corona was no exception. Sweden sees technology as a signifier of an advanced society, and therefore socially progressive. This wraps technology up into the self image of a tolerant, accessible, open-minded society, which is even more heightened in an art context.

But I must admit that personally I have completely failed at taking part in digital events this past year. I can’t do it. I feel an inherent awkwardness and I don’t know the social codes or couldn’t find an adequate point of entry. I found myself as a bystander, not really engaging. Even when taking place digitally, most online content was directed towards a local audience.

Also, I think there is a risk that the art experience is reduced to something informative when it is filtered through online events; exhibitions are explained instead of experienced. Art is dishonest online in some ways. I find it easy to forget that I am looking at photographs of artworks half the time. People are very easily lured that way. The unavoidable decision to replace physical spaces for art with online presences during Corona has exacerbated this dishonesty, creating a facade of activity. With institutions, exhibitions and events relocating online and reaching out primarily through social media these places also shifted from being a part of our daily lives to residing in the palms of our hands. With each institution or gallery advertising an endless scroll of events, live streams, interview and guided tours, engagement felt demanding and overwhelming. I chose hibernation instead. On the occasions I did manage to see some real life exhibitions last year, I was struck by an honesty and sincerity contained in works, as if they were stripped free from the machinations and hullabaloo of the art world. Plus; I did not have to maintain a distance.”