Stroom Invest interviews / curator Rieke Vos

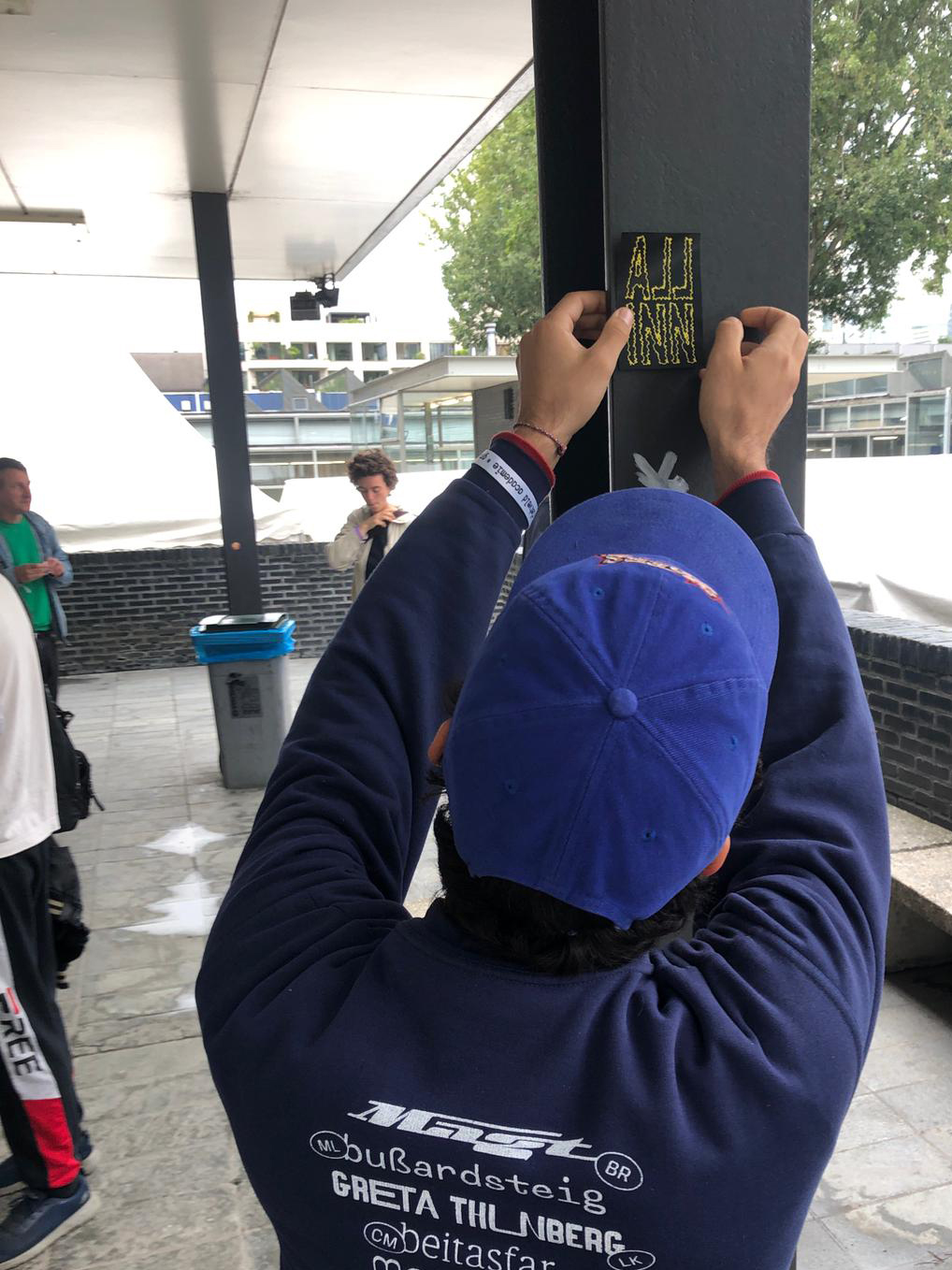

Being a curator for the recently opened home for contemporary culture – Het HEM in Zaandam – and previously for the NDSM shipyard in Amsterdam, Rieke Vos (1981, Arnhem) works in close exchanges and dialogues. While talking about her curatorial practice she refers to three projects in the former Dutch Weapon Factory called ‘chapters’: artistic programs that expand on the format of an exhibition by including concerts, (theatre) performances or even boxing matches. Each chapter is based on its own approach to the space, to really see its context and to seek freedom within restrictions and value in collaboration with invited guests – such as the creative entrepreneurial duo Edson Sabajo and Guillaume Schmidt, known from their streetwear and lifestyle brand Patta. While currently curating ALL INN, presenting work of 150 young, recently graduated artists from all Fine Art bachelor’s programs in The Netherlands, Vos doesn’t aim to present a talent scout platform. Instead, ALL INN promotes cooperation and offers tools in- and for the (young) art discourse itself.

Liza Voetman: You studied Art History at the UvA and participated in the Curatorial Programme of De Appel during 2010-2011. Interested in art, popular culture, architecture and urban life, you seem to have a broad background- and interest. How do these aspects relate to each other?

Rieke Vos: I don’t think it is so broad. For me, it’s really about the space where things touch each other. I have become interested in tendencies I currently observe in the cultural field, where artists are no longer either visual artist, or theater maker, or designer, but often embody all these roles simultaneously. Some people call it the ‘new homo universalis’ – I quite like this term. Many artists are visual artist, entrepreneur and DJs at the same time, and are looking for platforms that can accommodate this diversity in their practice. A well-known example is Joep van Lieshout. He is unmistakably a visual artist, but he also sells his work as design and even takes on the role of a real estate developer to build an entire cultural quarter in the port of Rotterdam. That is something that interests me. In addition, cultural platforms in the Netherlands are often pre-programmed. ‘This is a theater, where you sit in the dark’, ‘This is a white cube, where you walk through the rooms, and don’t sit down’, I am interested in opening up those frameworks, in line with what the artist needs. This fluid movement between various artistic forms also applies to the public, they also tend to associate an art work they see in a museum to a song they hear on Spotify. I am interested in these associative connections and what they tell us about our cultural awareness.

A context also has its frames. Can these frames become too restrictive, taking over your actions, your freedom?

My first job after graduating was at an architectural firm. I learned a lot from working together with people who approach restrictions as a positive thing, as something to work with. The frameworks, the boundaries can be very valuable, they stimulate reflection and can provoke very creative solutions. I think I’ve always taken this into account, whereas in visual art it often exists the other way around. To me, frames are something precious to keep in mind. With smart ideas you can get around these frames, which is a huge and interesting challenge.

For years I have been thinking about this dialogue [between autonomy and heteronomy], the question how to work autonomous through frames. How do you see this tension?

I work with students who are often looking for autonomy, but autonomy is not something you get. I don’t believe that there is such a thing as autonomous art within an autonomous area in which you, as an autonomous person, can express yourself completely autonomously. In many cases I think autonomy relies on the organization of (economic) conditions, so that you organize a state of being from which you have the freedom to do whatever you think is necessary. I think autonomy is something you kind of have to establish for yourself. In fact, a lot of art is actually about this quest for autonomy rather than an actual product of autonomy.

How do you continuously question the existing, driven from the context and architecture of Het HEM?

From the start, we made a very clear choice to not pre-program the spaces in the building. For instance, we don’t say: ‘This is a room for visual art, we paint the walls white and place bright lights from the ceiling’. For our three conducted chapters, we sought cooperation with people based on their view of society and used this perspective to put focus on developments in the cultural field today. We invited those people to take a seat at our programming table and compiled our programs in line with their views and interests. Through dialogue you are able to get new perspectives on how you can look at things.

Should artists, for instance, be able to establish a dialogue with the context itself?

No, if the artist doesn’t want that, I’ll do it with- or for them. A work of art has its own aura, of course. A good work of art expresses many things at the same time and preferably something different each time you look at it. A location does the same: it also embodies many layers of meaning. I find it exciting to recognize these two things, the work and the place, to look at them side by side and to let them reinforce each other. This usually happens in dialogue with an artist, I really like these collaborations; it’s a bond of trust.

Do you approach a place and work of art as equal forces?

No, I wouldn’t say it like that. What’s important is that you take all elements into account: you have to consider the artist, the location, but also the work of art itself. An art work may embody different meanings besides the ones an artist ascribed to it. Historical backdrop, political context, questions of gender or changing social structures and of course the location where it is currently shown or where it was shown in the past: these elements all leave their imprint on the meaning of an art work and we should try not to ignore them. Try not to say: ‘We’re not talking about X, now.’ I often refer to this approach as context-specific curating.

Can you tell us more about how time – and the way we live together – plays a significant role in your curatorial practice? Your practice doesn’t seem to be separated from our contemporary society, wondering about COVID-19. Is it one of your most important motives: current affairs?

Many of the themes I’m interested in are timeless, but I dó think I approach them from a time-based perspective, from the Now.

Do you feel yourself responsible in today’s society, being a curator?

Yes, it has to do with what I just mentioned. You can’t pretend things aren’t there when they are there. I recently gave a lecture on content-specific curating, which started with the idea of the White Cube. Technically a white cube is a modernistic architectural typography designed to keep the notion of time and space outside: this type of architecture can be found all over the world. Without windows and with bright lights from the ceiling you don’t really know where you are or what time it is anymore. I think context-specific curating is about always knowing when and where you are – metaphorically speaking.

White Cubes are known everywhere in the world, do you travel a lot outside of Europe?

I have been to South America a lot, I like to be in places where I am a bit overwhelmed in a way. Where I don’t fully grasp or understand everything I see around me, a feeling I really have while being in South America.

To question your own perception?

For sure, but I’m also very European. During Corona- and even before, I started questioning what is a good enough reason to take the plane somewhere. I’m considering this more than, let’s say, ten years ago. I took my first steps as a curator within the Curatorial Programme of De Appel. During the program we travelled a lot and a world opened up to me, that of the Global Curator, which was very exciting. Over time however, I’ve somewhat changed my ideas about this phenomenon. In recent years I’ve mostly worked in the Netherlands from a context-specific perspective and I find it very important to have a good understanding of the places you work in.

For those who haven’t been (t)here yet: what kind of place is Het HEM?

The building is 10,000 square meters, it’s a very rough building with a strong industrial vibe. But when you enter it actually has a very warm atmosphere, a living room feeling with a huge bookcase. From the moment we started we have always tried to create a place that is generous to the visitor. The primary language of Het HEM is visual arts, but within Het HEM many forms of cultural expressions are being presented, such as music. We have a fantastic music programmer in our team who invites DJs with unique record collections to come and play on our magnificent sound system. The way we develop our programs, in dialogue with invited guests such as Nicolás Jaar, Edson Sabajo & Guillaume Schmidt or Simon(e) van Saarloos, leads to programs that are not thematic but rather associative. We don’t claim to make exhibitions that tell you everything about a topic from an objective or observative position, instead its is our ambition to develop programs that embody the DNA of a certain cultural phenomenon.

So chapters are programmed chronologically over time?

Yes, the idea was to put the entire building in the context of such a chapter. To the extent that for instance even the cook in the restaurant would become a program maker, and proposed ways of translating the focus of our chapter into his menu. It links very much to what I said earlier about being interested in a cultural fabric that goes beyond visual arts alone.

Mid-November 2020 you will open a national fine arts graduation show, entitled ALL INN, presenting the work of about 150 young recently graduates art students. How does this project come about?

It’s huge, but fantastic: it’s organized entirely bottom-up. The initiative was born out of the very difficult COVID-19 situation in which many graduation students saw their graduation show go up in smoke. ALL INN is one graduation show for all nine Fine Arts Bachelor’s programs in the Netherlands. As the title suggests, we do not select the participants, it is specifically not a Best of Graduates presentation. We want to offer all alumni a platform. With 150 participants I look forward to ALL INN becoming some sort of beautiful mess. Having said that, the primary motivation of ALL INN is to create a platform for encounter and collaboration, to offer these young artists tools to establish themselves within the field. This desire and interest very much comes from the graduates themselves, from their collective concern: You have your diploma: And then what? I co-organize ALL INN with a group of about 30 graduates, they are an active part in every step of the preparations, like writing a Mondrian Fund application, setting up an Instagram campaign or developing a technical production plan.

On a more general perspective ALL INN is also a response to the impact of COVID-19 on the cultural sector, a sector that already struggles with economic precarity. This idea of coming together is related to that, we really hope that besides graduates many members of the art world accept our invitation to participate. Hence the title refers to an “inn”, a tavern or hostel, a place where you meet others while being in transit. The underlying question here is ‘how do we deal with the economic difficulties together?’ There are many economic benefits to be gained from cultural activities, various calculations show this. But often the values that are created through cultural activities do not land with the people who instigate those activities. We need to think how we can organize this better, because otherwise those cultural activities – and the values that come out of it – will gradually disappear. A couple of years ago the city of Berlin invoked a tourist tax, from which a large share ends up with artists, for example through the support of not-for-profit project spaces. How do wé [in the Netherlands] ensure that the value ends up where it is needed? This describes somewhat of a personal motivation for me to work on ALL INN.

To conclude, you both like to work in a public and semipublic space. In what context would you like to work someday?

This is kind of a job application question [haha]. I guess I would love to work at a museum someday, I would be very interested to develop a program that brings the voices of historical artists in connection with contemporary visual artists and designers, again looking at the cross-overs within the cultural fabric and the multitude of cultural expressions. I would like to bring to the forefront how certain historical artists are is not only present in the cultural awareness of contemporary artists, but also influence designers, performers, or musicians alike. Museums are very complex organizations, they carry a lot responsibility towards the preservation of their collection and the presentations towards their audience. These responsibilities often generate limitations. I would like to expand the possibilities of cross-overs, it is a challenge, but that is precisely why it interests me. To seek ingenious and innovative solutions within the given frameworks of these institutions.

With regard to the Stroom Invest Week: what do you hope to find, learn and/or discover during the week, for yourself and for others?

I really like these kind of curatorial trips. I love to be nourished with creativity and to spend time talking with artists, so first of all I will enjoy it very much. These studio visits are also really important for young artists, so I hope I will be able to give some fruitful input. And something else, a little secret: I live in Amsterdam, and I think the Invest Week is a very interesting model that could be implemented in other cities as well. So, I guess I will be looking at it from that perspective too.

Stroom Invest Week is an annual 4-day program for artists who were granted the PRO Invest subsidy. This subsidy supports young artists based in The Hague to develop their artistic practice so that artists and graduates of the art academy can continue to live and work in The Hague. To give the artists extra incentive, Stroom organises this week consisting of an evening of public talks, studio visits, presentations and several informal meetings. The intent is to broaden the visibility of artists from The Hague through future exhibitions, presentations and exchange programs. Stroom Invest Week 2020 will take place from 21 to 25 of September.