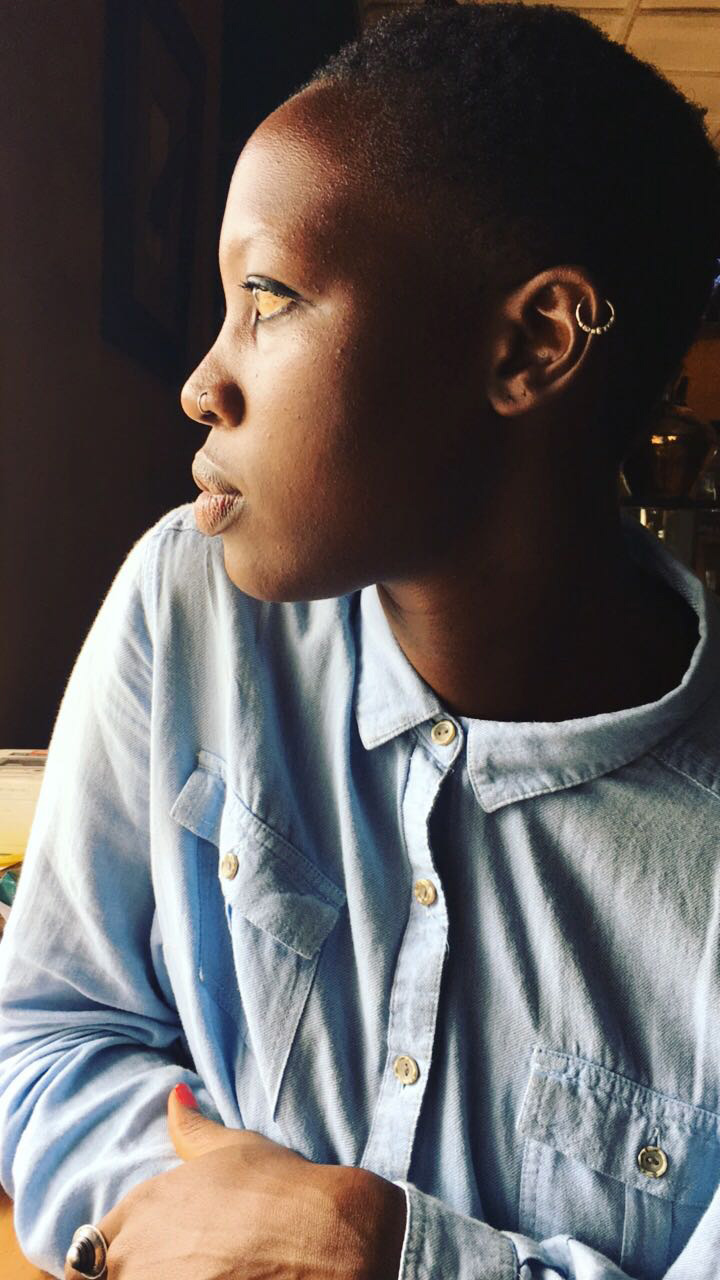

Stroom Invest interviews / curator #5 Renée Mboya

“I don’t know if there was ever a beginning in itself, not in the traditional sense of art school and coveted internships i.e. free labour. I was always organising something or the other, well before I knew it was ‘curatorial’ or called it that.“ Meet curator Renée Mboya in this 5th Stroom Invest Week interview.

Renée Mboya is a curator, writer and filmmaker from Kenya. She came to arts practice more or less by accident.

I was in law school at one time, imagining a completely different path for myself. It happened that I could no longer pay for my legal education and at that point I started to look for work. Arts institutions were the only ones that would hire me without a degree certificate – and always for roles that were focused at sanitising the presentation of artists in one way or another. Can you stretch this painting, paint this wall a whiter shade of white or polish this wood? The assumption always being that the work, what was referred to as ‘Africana’ then (by accident of location – and here I cling to the apartheid pun) did not belong in these spaces, and that the spaces refused, in violent ways, to allow the work be legible in its ‘natural’ form. It has always been violent work and I accept what penance I’m due for that.

The advantage, to me, of all that was that I spent hour after lonely hour of really intimate time with a lot of work (paintings, sculptures, photographs), dragging them in and out of storage and ‘playing’ with them – putting them up on the wall, laying them on the floor, up against the window, in the corridor by the kitchen. I have to suppose this improved my literacy and enjoyment of art in ways that would never have happened if I had come to art from a position of theory. I learnt about art in deeply personal and affecting ways before I realised that there was a canon of art history which suggested a conventional timeline of ‘old masters’ and foregrounded one culture over another.

Painters, musicians and fabulists of immense talent and imagination, Renée comes from a long line of artists. Can you elaborate a bit more on the role art and culture played in your childhood?

There was always a performance about things in our household, and I remember this prevalent sense of animation around objects in particular – that the cup and the spoon were deep in conversation and that if you waited long enough they might tell you what was going on.

The first time I was ever conscious of the fact that art and culture might be a deliberate practice and not incidental to my family life was receiving a postcard in the early 90s from my father who lived in Dar es Salaam that was a copy of a E.S. Tingatinga painting. I think the heritage of the Tingatinga movement is certainly still a very strong influence on me because that imagery makes it possible to think about the different dimensions of art — craftsmanship, politics, performance, folklore, orature, the ways in which art and artists have been criminalised and relegated to the subculture – witchcraft, pornography . . . there’re a lot of layers. When I look at art now I try to see it from that perspective, through the eyes of a much younger me, because I have to hope that before I had English beaten into me, before representation was a question of survival, there was a narrative there that wasn’t so loaded with rupture.

What do you consider the major theme in your work?

Biography is certainly a very prevalent theme in my work. I think this comes from ageing, and the fact that I am now closer in years to my old age than to my childhood. It’s nostalgia really.

When I did my diploma at de Appel a couple of years ago, one thing that was particularly surprising to me, and especially in art critical and intellectual spaces, was constantly having to explain myself, where I had come from and how such a thing as me could exist, as if I had come from an alien planet and not just Nairobi, which has direct flights to Amsterdam at least twice a day. In responding to this circumstance I saw a need to use biography to stitch together a wide range of material – to renegotiate fraught identities as a way of creating thought, image and writing that is a verb, a witness report of the present moment. This was my way of convalescing my story, my history, from this frontier mentality, where someone has always just discovered something, or that we, the proverbial African ‘we’, are ever emerging, coming into enlightenment or reforming (converting) into something better (read whiter). It was important to me to be able to say “my mother said” and this be the basis of my entire intellectual approach because it was my way of augmenting the fact that this is also knowledge and it cannot be dismissed just because it didn’t come out of a Western university somewhere. Ngugi wa Thiongo talks about ‘moving the centre’. This was me finally realising that my ‘centre’ and the way that I had always experienced it was being ignored in these spaces where I had naively hoped to better articulate my cultural power.

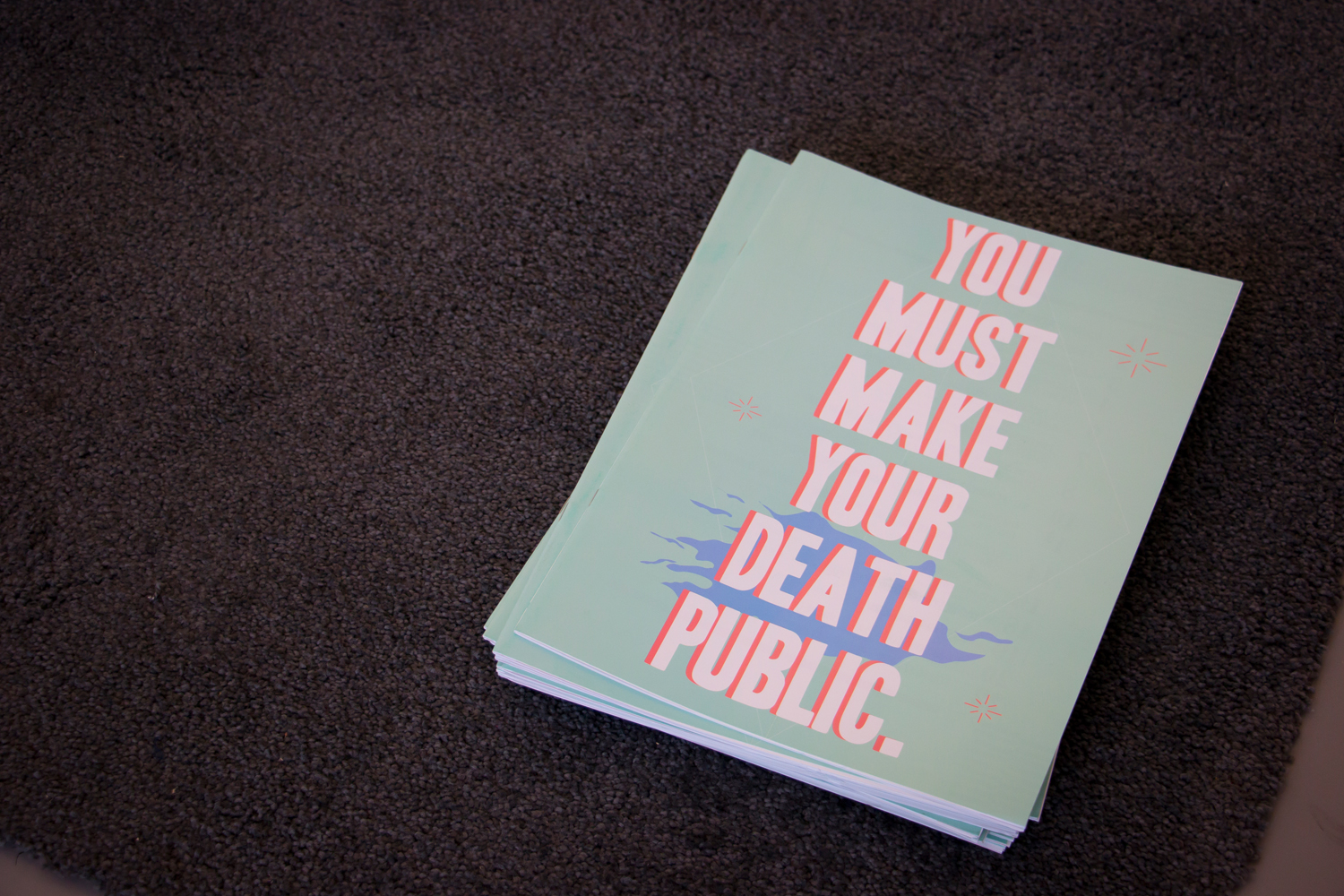

De Appel Curatorial Programme is an educational platform in Amsterdam since 1994 for the advancement of the theory and practice of exhibition making. Renée was one of the participants in the 2015/2016 edition. She curated ‘You Must Make Your Death Public’. What are you currently working on, Renée?

My current preoccupation, and especially as I’ve been making more films myself this past year, is with the 1966 film “Africa Addio” also known as “Africa Blood & Guts” – and I suppose this latter interpretation of the title leaves less to the imagination. It’s a consuming piece, agit-ethnography in every sense of the term and it has become something of an obsession for me. This year I’m trying to find different ways to confront it, though I can barely stand to watch it. How do we speak back to a spectre — this racist, colonial, sectarian ghost — that is always present? For me this goes back to the question of biography and representation. How we see ourselves verses how the world sees us and who gets to decide how we are seen. Watching “Africa Addio” for first time I finally really understood the power of image, and was able to interrogate my own role in relation to that. Every decision I make, every curation, is a power play, every shot is an opinion; and it’s complicated.

Can you tell a bit more about the art scene or the art climate in Kenya? And does it affect your work?

The art scene in Kenya is just like it is anywhere else really. There are a lot of new initiatives and new spaces popping up every day, which are motivated and sharp – challenging the discourse and structures that have kinked the narrative, and working hard and fast in a country where there is hardly any infrastructure or policy support for the arts. There is also a lot of stuff that is really dull and myopic, and that is something I’m trying to articulate more as I establish my own critical scope. That it’s okay to say some things are boring and that nothing happened today.

The result of this for my own work is that I’m unlearning the curatorial arrogance that an institution with a tradition like de Appel tries to impart on you. I know now that sometimes it’s okay to just watch and wait, and that silence is also a place of action and that there is momentum to be built from there.

Kenya is also the place where I am most sensitive now to the burden of my context. What does it mean to be of a place that for at least three hundred years has been denied, and have to wake up every day to prove your existence? My response to this, my modest act of resistance, is to prioritise play in my approach. If it’s not fun I don’t want to do it, and in a space where being ‘serious’ is a prominent part of the respectability politics, this means I don’t get invited to as many things as I used to. Working in Kenya is isolating and liberating at the same time. This is the balance I try to broker every day.

Ageing and nostalgia, you mentioned that before. How do you look at the future? Does it stress you or the contrary?

I have no stress about my future no. It hasn’t happened yet! The present on the other hand is marred by this constant anxiety that I might be making the wrong choice, now, and again, now. It’s the same anxiety I have in my work, both film and curatorial, I have to make choices and be confident in those choices, but mostly I’m guessing and hoping for the best.

You are a writer and a filmmaker, does one strengthen the other?

For me the writing and the filmmaking are the same thing. I started making films because I was at a point in my writing where I was starting to be very self conscious about my process, getting stuck at every attempt and feeling very oppressed by the amount of research that was gathering dust on my desk. Film gave me the lightness to make mistakes in my work and to make work that was silly and experimental and I’m really thankful for this.

The work allows you to work and meet many people. Which art initiatives inspire you? And why?

I had the good fortune to see a lot of Arthur Jafa’s work in London last year. “A Series Of Utterly Improbable Yet Extraordinary Renditions” is on my mind right now as I think about what it means to look into a cultural archive and reorder narratives in ways which prioritise “black pleasure” and “black joy”. A lot of the archives that I’ve been looking at, the colonial and post independence archives, don’t make much space for this, and in many respects reinforce the institutional violence of the colonies. Looking at these archives, living with these archives, the thing that worried me most was how familiar these images are to me. That I recognised myself in this depiction of a ‘savage’ Africa, despite the fact that I had never lived in it. I think Arthur Jafa’s work is important in challenging us to read image in different dialects.

What do you like most, working solo or working in collaboration?

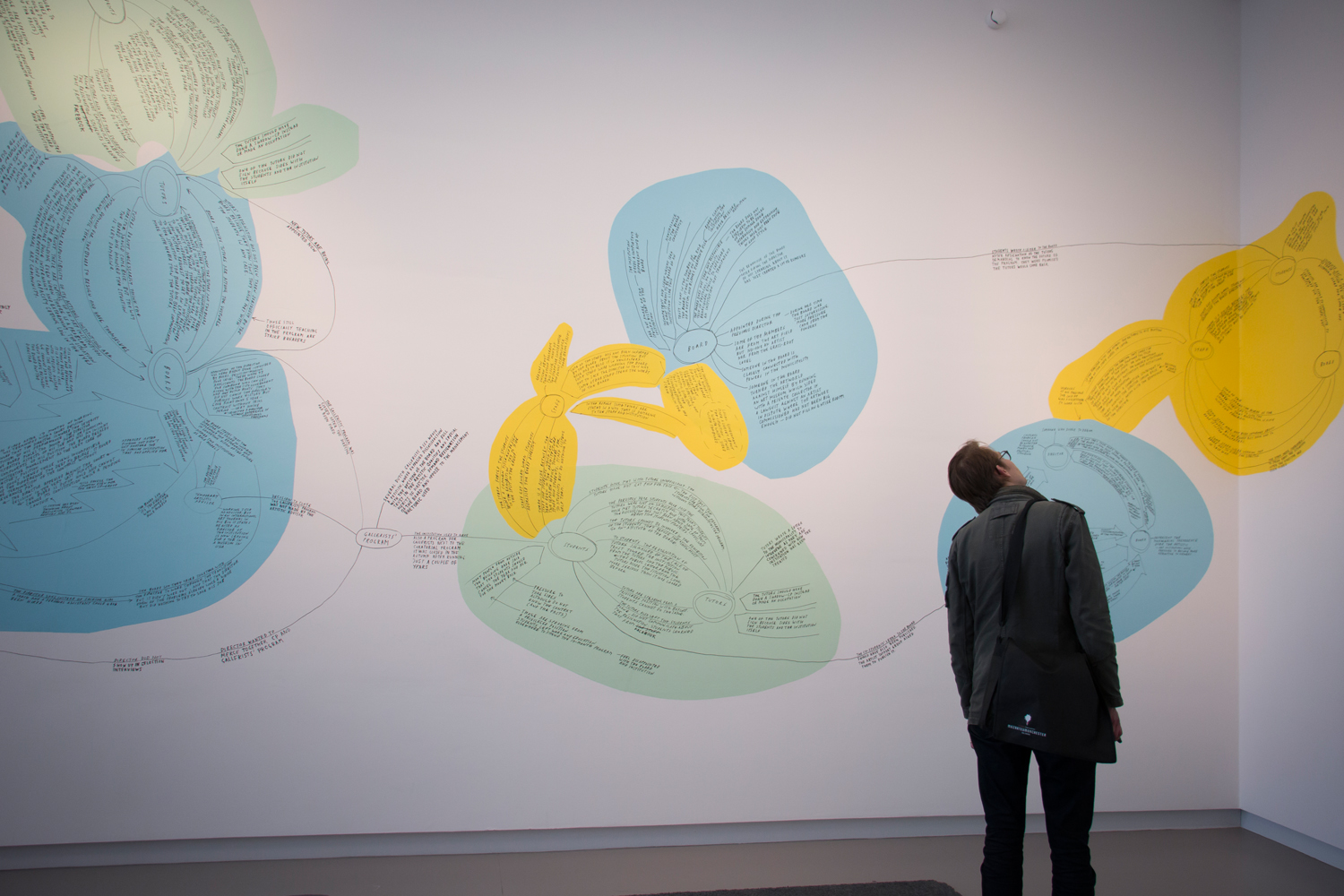

I think of myself as a builder in some ways. I love the work of putting pieces together and being elbow deep in the less elegant work of ‘building’ the actual physical spaces which host works of art. I like to go home at the end of the day having spent the day with the carpenters or the painters or with my fingers stained black from the printing press. It’s important for me always to put my body in the way of the work, to try and see things with the same degree of detail an artist might. My ambitions here are really simple but they rely very much on the skills and guidance of other people, and so working in collaboration is absolutely essential.

I think sharing space is important to me because coming from a place that is peripheral to Western art discourse, it’s a way of flattening the hierarchies that tell me, and other art workers, that we do not belong in these spaces, or that some kind of correction needs to happen in order for us to stay.

I enjoy the work that I do by myself, and I recognise the privilege of having the time and psychical space to do it but I find that I trust myself; my labour, my experience, my expertise and my knowledge – much less when I’m not able to share the things that I’m accreting.

—————————————-

In a collaboration between Jegens & Tevens and Stroom Den Haag a series of interviews will be published with (inter)national curators, artists and critics participating in Stroom’s Invest Week 2018.

The Invest Week is an annual 4-day program for artists who were granted the PRO Invest subsidy. This subsidy supports young artists based in The Hague in the development of their artistic practice and is aimed to keep artists and graduates of the art academy in the city of The Hague. In order to give the artists an extra incentive, Stroom organizes this week that consists of a public evening of talks, a program of studio visits, presentations and a number of informal meetings. The intent is to broaden the visibility of artists from The Hague through future exhibitions, presentations and exchange programs. The Invest Week 2018 will take place from 18 to 22 June, the public evening is on Wednesday following the exhibition My Practice My Politics.