Stroom Invest interviews / curator Tereza Jindrová

Tereza Jindrová (b. 1988, CZ) describes her practice as a multi-role play. She is taking on several roles, that are naturally intertwined – curator, writer, researcher, educator. We caught up between travels and funding application deadlines to discuss her own curatorial goals, thoughts on (ir)rationality and upcoming projects.

Could you give me a short introduction about yourself and your background?

I live and work in Prague, where I was born and where I probably would like to grow old, because I really love the city. The local art scene is currently very vibrant and offers interesting opportunities to develop yourself but also to influence things on a broader scale. But of course, I also like to spend time abroad, experiencing different contexts and I actually traveled quite a lot in the past years as part of my work. I’ve also been on several curatorial residencies, for example in Milan, London, Tel Aviv or recently in Helsinki.

I studied art history at Charles University in Prague, but finished my master’s degree at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague. During my studies, I was constantly moving more and more towards modern and then contemporary art and theory. This attracted me to curating and working directly with contemporary artists.

I continuously worked in various art related positions during my studies – as a gallery production assistant in Centre for contemporary art MeetFactory, as a manager of distribution for Flash Art Czech & Slovak edition, as a public educator in the National Gallery in Prague, as a fine arts editor in A2, a Czech leftist cultural biweekly, etc. So I would say I have quite a good idea about different roles and positions in the art field. Looking back, I appreciate all the practical experiences and the way I gradually developed my skills and knowledge. It helps me to stay in touch with different layers of what making exhibitions means and to keep a sense of modesty in a way. Currently I’m working as a curator and researcher at Jindřich Chalupecký Society, a platform for Czech art in an international context; and on a long-term basis I’m also cooperating with artist-run gallery Entrance in Prague.

You just finished up a month spent as a resident at HICP – Helsinki International Curatorial Programme. What were you planning to accomplish there going in? Did your plans change at all during the month?

It is well known that artists in Nordic countries are more traditionally invested in the questions of ecology and environment. The Finnish culture and identity is very much connected with nature, so I was focusing on the ways artists in Finland work with the nature-culture or human-animal relations. I was visiting art institutions, meeting artists and curators and organizing a temporary reading group, discussing texts from the fields of eco-feminism, post-humanism or animal rights.

I’ve met a lot of interesting people and our discussions also brought me back to the role of artists in society, and to the issues of gender and knowledge, which are undeniably deeply entangled with the problems of environment and global climate change we’re now experiencing. Of course I didn’t have time to meet everybody or see everything I’d like to, but hopefully I will have the chance to revisit Helsinki this September and take part in a 4-day public program called “Rehearsing Hospitalities” organized by Frame.

Where do your curatorial ideas generally come from? — reading? others? previous work? life experience?

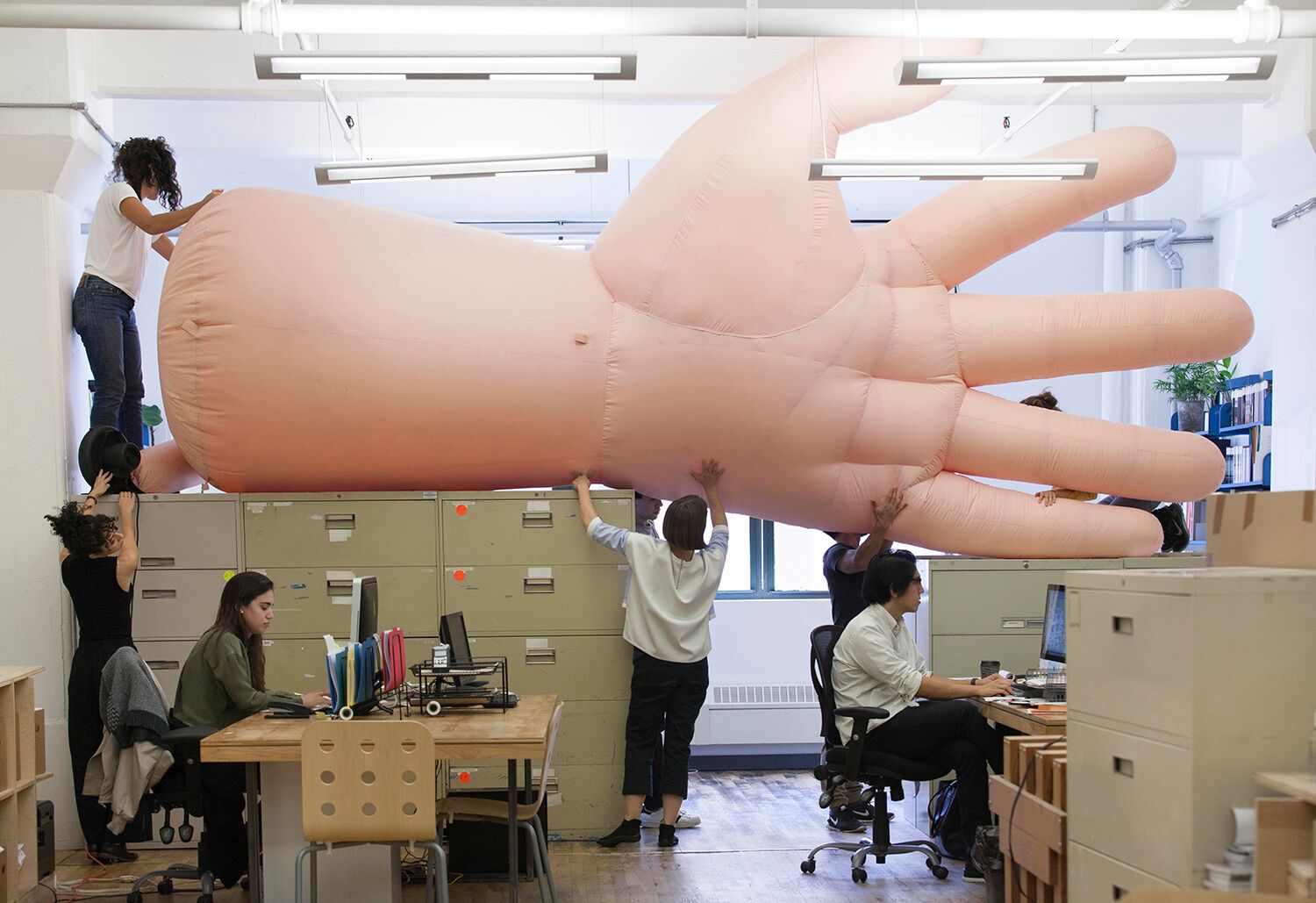

It really depends on a particular situation, but mostly I would say that it comes from observing art itself – at exhibitions, biennales, in magazines. Every curator is creating a kind of virtual database of artists and artworks in her head. Sometimes some topic or motif emerges more clearly and powerfully in multiple works. These connections inspire me to explore the common aspect more deeply and find more artworks with similar sensibility. This can eventually lead to an exhibition. In other cases, I respond to a specific context, such as the spatial or institutional conditions of a certain place. An example of that was the processual project called “Workplace”, where I invited various artists to work directly in the gallery space, so what was exhibited was the artistic work itself. This project was based on my interest in the issue of evaluation of artistic work and its precarious conditions, but also on the particular gallery space, which is very different from the canonical white-cube, and its audience, which is mostly people with no experience with what it means to work as an artist in the 21st century. The third category are shows like the one I’m working on currently, where I was inspired by a particular theoretical text about hydrofeminism by Australian theorist Astrida Neimanis. So, I can’t really name only one main source or way of inspiration.

What role does writing play in your work?

Writing definitely plays a key role, as my main tool for expression. As a kid I used to draw and paint a lot, but quite early on I also began to write my little stories and poems. When I was choosing a high school, writing actually helped me to decide – for a while I was also considering going to an art school, particularly to study painting, but the self-identification with writing was stronger. Fortunately, because I would most probably be much worse painter than writer. However, my approach towards writing is definitely changing in time: it was different during my studies at university when I was writing art critiques and reviews quite extensively and won an award for young art writers. After that, I worked as fine arts editor and I was not just writing myself but also editing texts by other authors, which was quite an instructive experience for me in many ways. In my current situation, I don’t have time to publish my writing that much anymore, so my main textual outcomes are curatorial texts or texts about artists I’m working with. But, as much as it is a cliché in these times, I have to say that I would like to find more time to write again more consistently.

In your eyes, what does the ideal relationship between artist and curator look like?

I believe that every curator has to admit to herself that artists can survive without curators, while it is more difficult to imagine what a curator would do without artists, i. e. without those who actually produce art. With this perspective in mind, a curator should keep a sense of responsibility towards the artist, but also to the viewer, because she often plays the role of a mediator between art/artist and the audience. On the other hand, it is obvious that most artists also very much need curators, as partners for discussion and advisers or as an organizing force in their work. Curators can be a passionate counterpart for an artist in a different way than other artists can be – not least because the curator does not produce art as such herself, so she does not compete with the artist in any way. Personally, I’m always happy when I can build a relationship based on trust between me and the artist and when I can facilitate a more complex and elaborated outcome of their work.

An exhibition you curated recently in Prague, Healing 2.0, highlighted our present day approach to health and healing. Does the level of reality or fiction that viewers take away from the work concern you? Or is it more exciting for you to have it exist somewhere between?

I have to say that for me this exhibition was quite a complex project and its aim was to affect the viewer on an intellectual and emotional level, but also to attract the senses and remind the viewer about their bodily presence. I didn’t really think that much about the duality of reality and fiction, because many of the exhibited works were actually somehow blurring these categories. Many of them could be seen as starting points for speculation – for example the series of works by a Czech artistic duo, Pavel Příkaský & Miroslava Vačeřová, was raising a question about the use of animals in medicine and genetic hybridization between human and non-human. These works do not present either “reality” or “fiction”, but occur just somewhere in between and therefore stimulate our imagination and critical thinking.

I’ve seen the word “rational” appear several times describing your curatorial interests. How important is rationality versus intuition in your practice?

I believe these two aspects should coexist. A good curator should have a certain intuition to follow, but also be able to work rationally and be structured, when doing a research etc. But what I’m referring to, when mentioning the duality of “rational” and “irrational” in my current curatorial interests, is the production of knowledge in general and its connection with power. Traditionally, the Western/modern culture has valued rationality highly and has, in fact, created its fundamental social institutions and practices specifically in order to suppress irrationality. However, it is obvious today, as many authors have noted in the past decades, that not only are the old kinds of irrationality still alive, albeit in unexpected forms, our modern rationality itself creates new ways of irrationality. I believe that understanding this relationship is now more important than ever and that art is the best avenue for its exploration.

Could you describe a typical day-in-the-life?

Describing a “typical day” is actually quite a difficult task for me, because my work days are very dynamic and variable according to the current projects and obligations. As I mentioned, I work full time for Jindřich Chalupecký Society, but our working model is not based on 8-hours sitting in our office. Sometimes our schedule is more relaxed and we can work from home with just a few meetings during a week, sometimes we’re working late nights and weekends, especially when we’re finishing bigger exhibition or applying for grants. It is actually not so easy for me to distinguish between my work time and free time, because I’m invested into art also on a freelance basis, working on smaller projects with friends, or just visiting art exhibitions and museum during my vacations. So being in the art field is somehow a constant state of mind. But I think this is the way of life for most art professionals.

Can you think of a contemporary curator you look up to as a role model?

I probably can’t name a single curator as an “idol”. But I’m looking up to curatorial practices that are based on intersectional feminism, social and ecological responsibility, diligence, respect and appreciation towards other cooperators and colleagues and strong curatorial visions. This might sound a bit too superlative, but I can say that I have these kind of people around me, people who are at least trying to think and act with such demands for themselves and that is encouraging.

Do you have any exciting upcoming projects you would like to mention?

Currently I’m working on a show called “Interconnection: On Bodies of Water” which will take place in Swimming Pool project space in Sofia and will be opened at the end of June. This show is a part of an ongoing project “Islands: Possibilities of Togetherness”, which we established this year with my colleagues in the Chalupecký Society. The project is focusing on different forms of coexistence and mutual relations and bonds between individuals and collectives.

My exhibition, prepared together with my colleague Veronika Čechová, focuses on the motif of water as a condition for life, on circulation and merging of life forms as well as on the search for a non-human perspective where the human is only a part rather than the highest life form within the ecosystem. This conceptual framework was inspired by Australian theorist Astrida Neimanis, who proposes the term “hydrofeminism” to reflect the post-humanist, materialistic notion of the subject/self as fluid and ontologically related to “others”.

Do you have any expectations concerning your time in The Hague?

I’m very much looking forward to meet all the selected artists and discuss their work, as well as meeting the organizers and other professionals coming to take part in Stroom Invest Week!

—————————————–

In a collaboration between Jegens & Tevens and Stroom Den Haag a series of interviews will be published with (inter)national curators, artists and critics participating in Stroom’s Invest Week 2019.

The Invest Week is an annual 4-day program for artists who were granted the PRO Invest subsidy. This subsidy supports young artists based in The Hague in the development of their artistic practice and is aimed to keep artists and graduates of the art academy in the city of The Hague. In order to give the artists an extra incentive, Stroom organizes this week that consists of a public evening of talks, a program of studio visits, presentations and a number of informal meetings. The intent is to broaden the visibility of artists from The Hague through future exhibitions, presentations and exchange programs. The Invest Week 2019 will take place from 17 to 21 June.