The Archive is present in design’s futures

The warmth of soup in a glass bowl

The graduation show at the KABK is a festive time of the year for the young artists and designers populating The Hague: a time where a space that is often mundane, sometimes stressful, becomes a collective gathering for different generations of students, their families and friends, neighbours, passers-by. Under this premise and spirit, the class of 2023 in the graphic design department presents their show titled “good soup” — a nod both to (audio) memes and to a collectivity that homes family histories, diverse backgrounds, and the simple rituals that make us human. I found the glass-covered upstairs place (which, as a former student myself, always feels like coming to a childhood home) carrying a lightness that I haven’t seen in the last shows: the classrooms-turned-exhibition-spaces filled with colours and tactility, joyful gatherings and return to craft, storytelling and curiosity, in what was clear to be a group of young designers who were given the space to question the discipline and break its borders, through fascinations and enquiries, critical stances and open-ended paths — given the space to do exactly what art school is for, to try every single possibility.

Perhaps because a lot of their studies were spent experiencing an art academy from their bedrooms, a common theme in the overall exhibition I experienced was ‘publicness’, or publishing: this idea of bringing something into a collective, open space, distributing knowledge and tools, start conversations. From a mobile installation that puts people answering questions in the street to a table inviting collective drawing sessions, these students clearly see design as commoning. I, too, see myself in such motivation and I have always been fascinated by background operations, the infrastructures and networks of knowledge, and the roads that lead it to where it needs to go. Who gets to be remembered, and how do we access memory – these are questions I’ve posed in my work as a designer and researcher. They too seem to live in Lara Dautun and Patrick Hutchinson’s minds, the two students I encountered at each end of the exhibition space and that approached the archive as the main subject and method during their graduation projects.

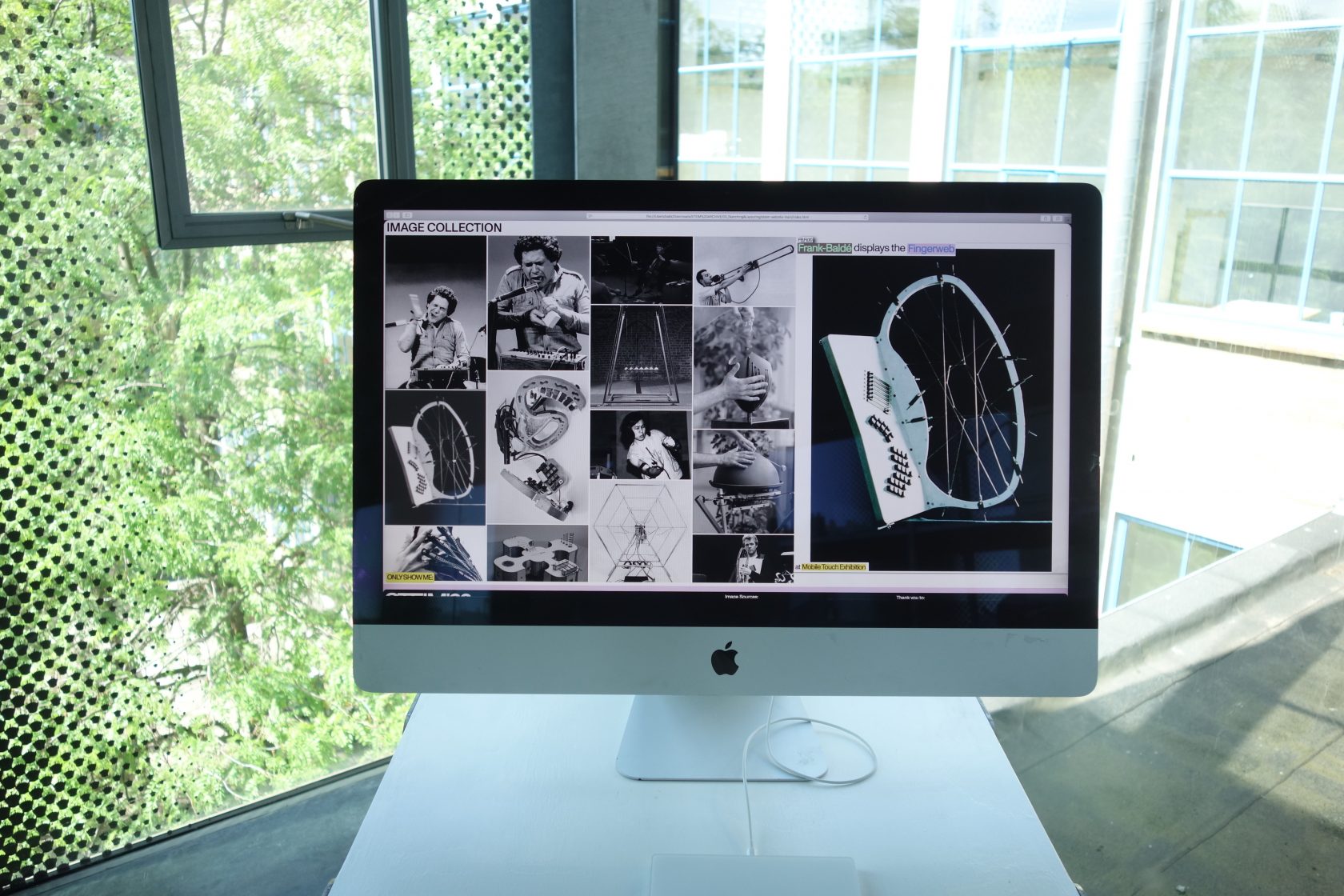

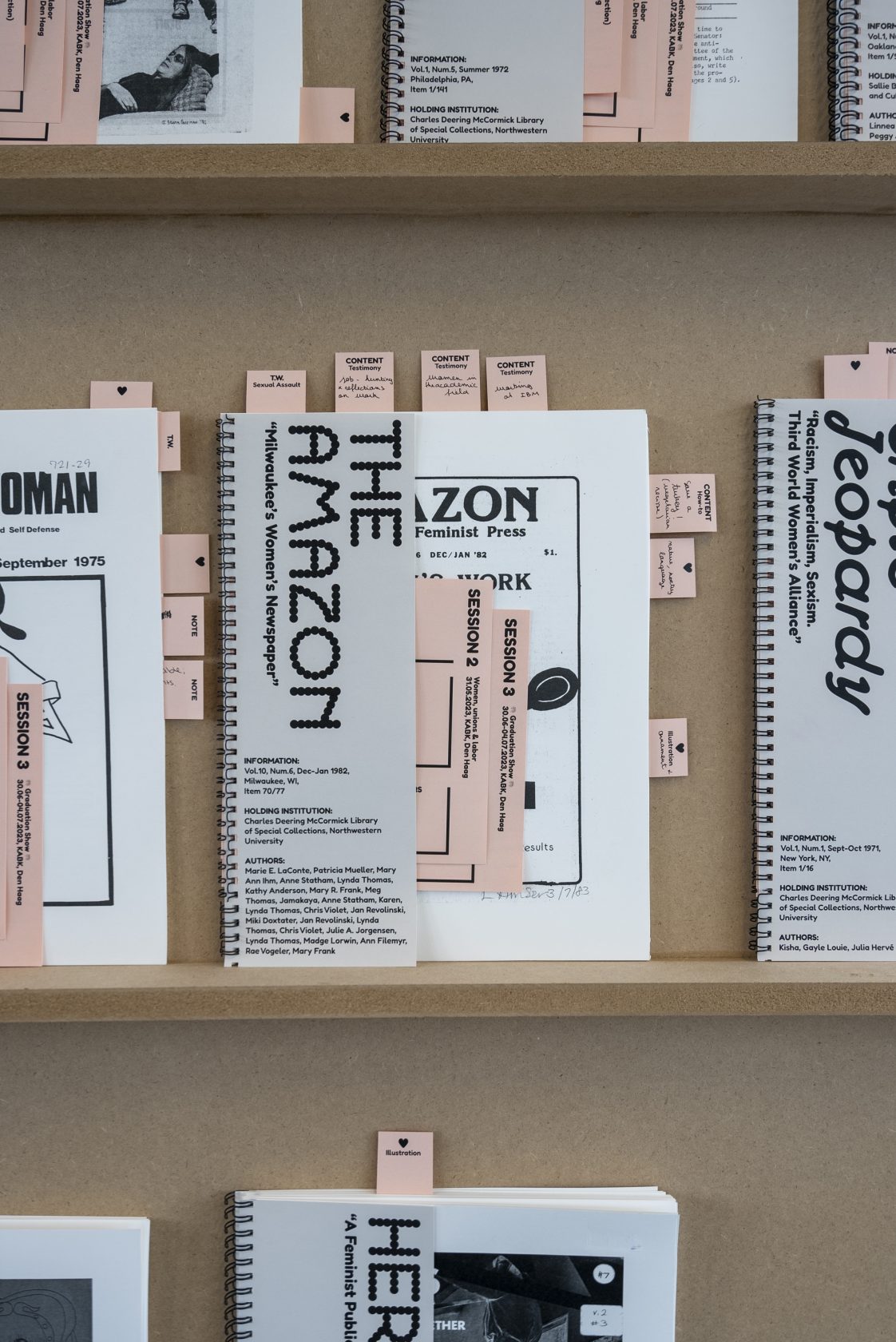

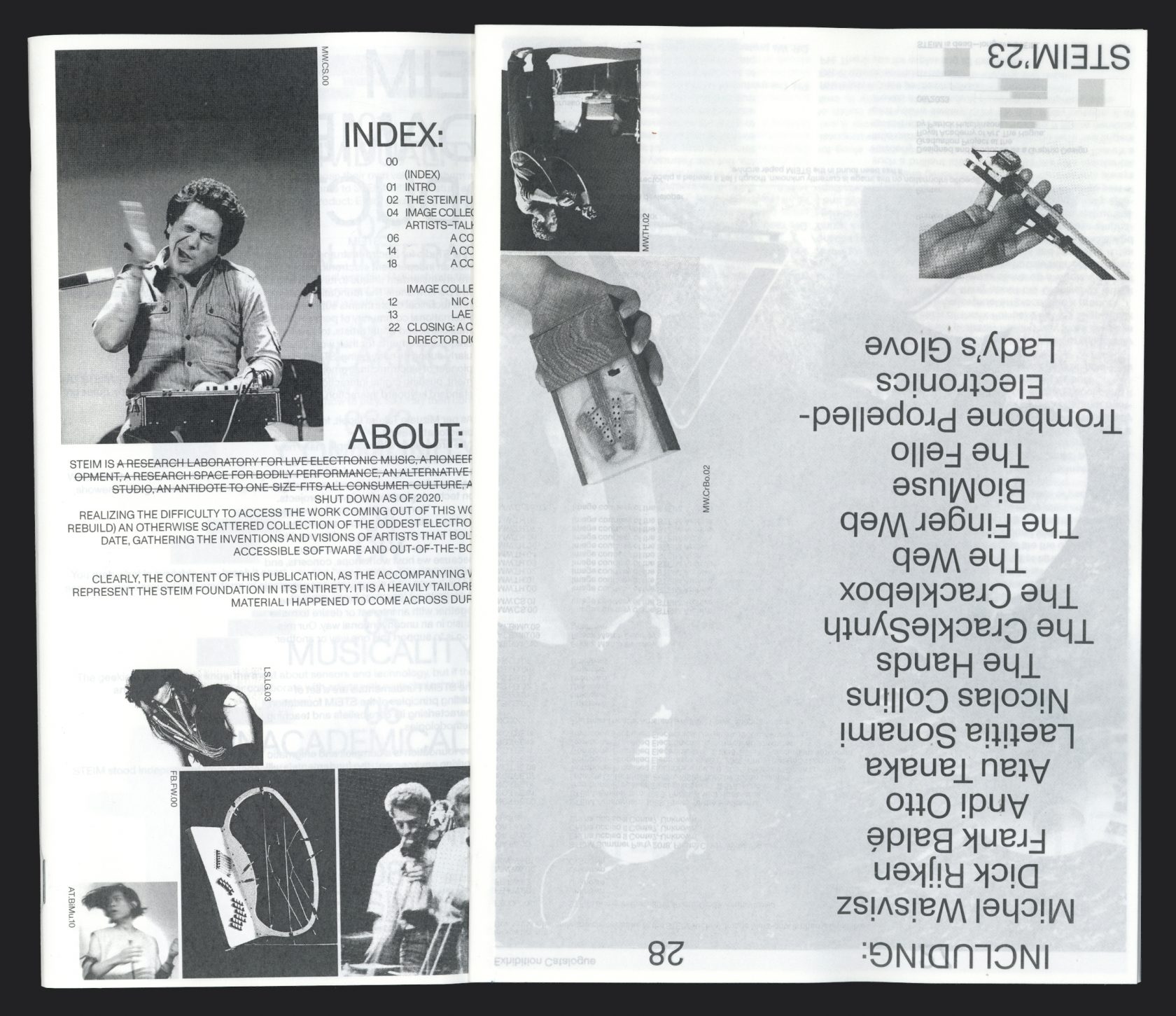

I’ve always found that graduation projects, even if unconsciously, find themselves as works made up of little pieces the students will collect over the years, interests that pop throughout assignments and classes — and at the end, we find that red thread, that was there all along. Patrick found himself in an exchange programme in Finland when he was introduced to experimental electronic music and STEIM (STudio for Electro Instrumental Music), an Amsterdam-based centre where artists could come together to build experimental musical instruments, exchange knowledge, be in residency and the developing live performances. In 2020, the STEIM Foundation had to close its doors due to funding cuts nationwide. The question of where and how to archive 53 years of history, materials, instruments and documentation became visible to Patrick when motivated by an archive-based assignment, he got in touch with some members. When presented with the opportunity to develop an almost year-long project, all the pieces came together, and Patrick is now in collaboration with STEIM, “build[ing] an otherwise scattered collection of the oddest electronic music instruments he had seen to date” and making an online archive that will go beyond a school assignment, STEIM’23. In the exhibition, for now, the visitors could see a prototype website with a curated selection of material, as well as a zine containing interviews, image material and research findings. For Lara, it didn’t seem like a difficult choice, but rather a serendipitous yet intentional journey in what seems more like a life-long work than a graduation project – her thesis on feminist publishing and feminist printing movements in the second-wave feminist movement moved Lara through archives and stories of past and present and led her to encounter the gaps and silences in the access to knowledge and to herstories. Her project, The Amateur Feminist Library, then becomes an attempt at opening up the archive and the library space as a communal feminist gesture, addressing the gaps of hegemonic history.

Designing the Archive

Like memory, institutions, history — the archive is constructed, designed. Both of these projects highlight the ways in which design practices can influence and build archives, not just through their interfaces but in the ways gateways are opened and how information is accessed. Beyond aesthetic choices, which can, of course, produce more eye-catching, interactive archives, design also establishes hierarchies (of how something is visible, what gets selected first) and relationships of content that will inevitably change how we access archival material — and its access, we will see further, is imperative for its liveness. In the STEIM archive prototype website, we encounter references to mixing software as background moving shapes, modernist typography and an easy-to-navigate, image-filled website which transports its 70s archival material into the present. Contrasting to the well-designed interface of this prototype, I can imagine what the STEIM foundation’s space looked like before its disappearance: rooms filled with boxes, chaotic entanglements of wires and cables, (parts of) instruments. Designing community archives, as it’s the case in both of these projects, is also, to a certain extent, to smoothen its edges. Archives like feminist zines and publications or experimental music networks work in a DIY spirit, ad hoc solutions and scarce meta-data. Designing the archive might involve a certain sanitisation, but while we clean its borders we also make it accessible.

Both Lara and Patrick have re-imagined the archival material they are working with in line with their design concepts, motivations, and needs of the communities they want to connect to. For The Amateur Feminist Library, it started by encountering the raw material of thousands of publications that had been scanned by librarians across the world, and placed in a collection titled “Independent Voices” on JSTOR, “an open-access digital collection of alternative press newspapers, magazines and journals, drawn from the special collections of participating libraries”. Lara worked towards a re-invested archive that passes the lines of JSTOR’s inaccessibility and opened up the Labour of the archivist/librarian — each publication now sitting in the space waiting to be re-thought through new meta-data, keywords, and annotations. Alongside a beautiful re-design of typography and image, the publications become activated, combining that DIY spirit into a networked reality through open-source tools including Scrapy, Pngify, Bookify and Librarify (that are yet to be published). As for STEIM’23, the close and personal contact with members of the network allowed Patrick to contribute the meta-data collectively, activating the archival material with interviews and conversations that continue to bring the ad hoc spirit to a more complete and relevant collection.

The Archive as (public) space

Creating interfaces and opening up the archive in more accessible ways: these are all strategies to see and read the archive as collective, public space. And this is when it becomes the most interesting — when from a network and community people, into collections, becomes again a community, open to annotations and footnotes, comments and additions — and when it is truly activated as present and potential future. Something of significance, data heritage we could say. The collective space of the archive, as an old space of data, also allows us to reflect on the kinds of information we retain and collect: what is the tole of design in transmitting and organising data and memory? What gaps could we still fill and what could be erased? What structures do we build to remember and facilitate further memory-making?

Both of these young designers have focused on the archive as space, and recognising that it’s the multiplicity in voices that will make it a meaningful space. And this wasn’t an afterthought but rather a tool they used throughout the process that led up to the exhibition. Lara’s feminist library was conceived through a series of workshops, which invited participants to browse the publications and “become a librarian” themselves by tagging content, adding keywords, and making comments. Those publications, activating through such workshops, are seen in the exhibition space, as well as a table with the same set-up and instructions, continuing this process, ultimately making that data part of the wider collection in feminist archives. For Patrick’s experimental music archive, this event also ended up being a network reunion. The project allowed old members to see each other after some years, and connect again over their shared passion. In the future, Patrick plans to continue the collaboration to make this into a community archive (the communal aspect of the “network” archive is based on ideas developed at STEIM prior to his intervention, specifally by researcher Hannah Bosma, and many more contributing), allowing others to upload their archives and collections that relate to STEIM, growing its database — with the passing of time, a lot of instruments and documentation were spread around the world.

Over the years, I’ve witnessed “star” objects or spaces in graduation shows, popular mediums or themes that flowed through classes and even departments. Perhaps as a sign of platform fatigue, now it seems to be time for the archive to become part of design’s futures.