Forms of Life with Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian

It is a muggy day when I arrive at the Tate Modern, struggling as always to find an entrance, the many slit-like sliding doors concealed in broad Victorian brickwork. I am here to see Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondriaan: Forms of Life, one of the Tate’s yearly blockbuster shows, an iteration of which will grace the Kunstmuseum Den Haag at some point this autumn.

I am keen to see the work of af Klint, an artist who is finally getting her dues. However, it rankles me that the powers that be seem to feel her legacy must be propped up by one of the ‘big cheese’ men of art history. As someone who never took much interest in the canon of abstract art, on moving to The Netherlands, Mondriaan’s work seemed to me simply a ubiquitous geometric pattern, cropping up on everything from stationary to PVC outfits in the window of certain sex shops.

However, with my eyeballs hungry to gaze upon the phosphorescence of af Klint, I found that same gaze softening towards Mondriaan. The alchemy of this exhibition, that which makes this double-billing plausible, is that it positions af Klint and Mondriaan together as kindred spirits, albeit ones that never met.

It begins with the early works of each artist, one in Sweden, the other in the Netherlands, each painting the landscapes, flora, and fauna around them. The precise rendering of plants by each artist works as a sort of origin story — it can only get more abstract from here.

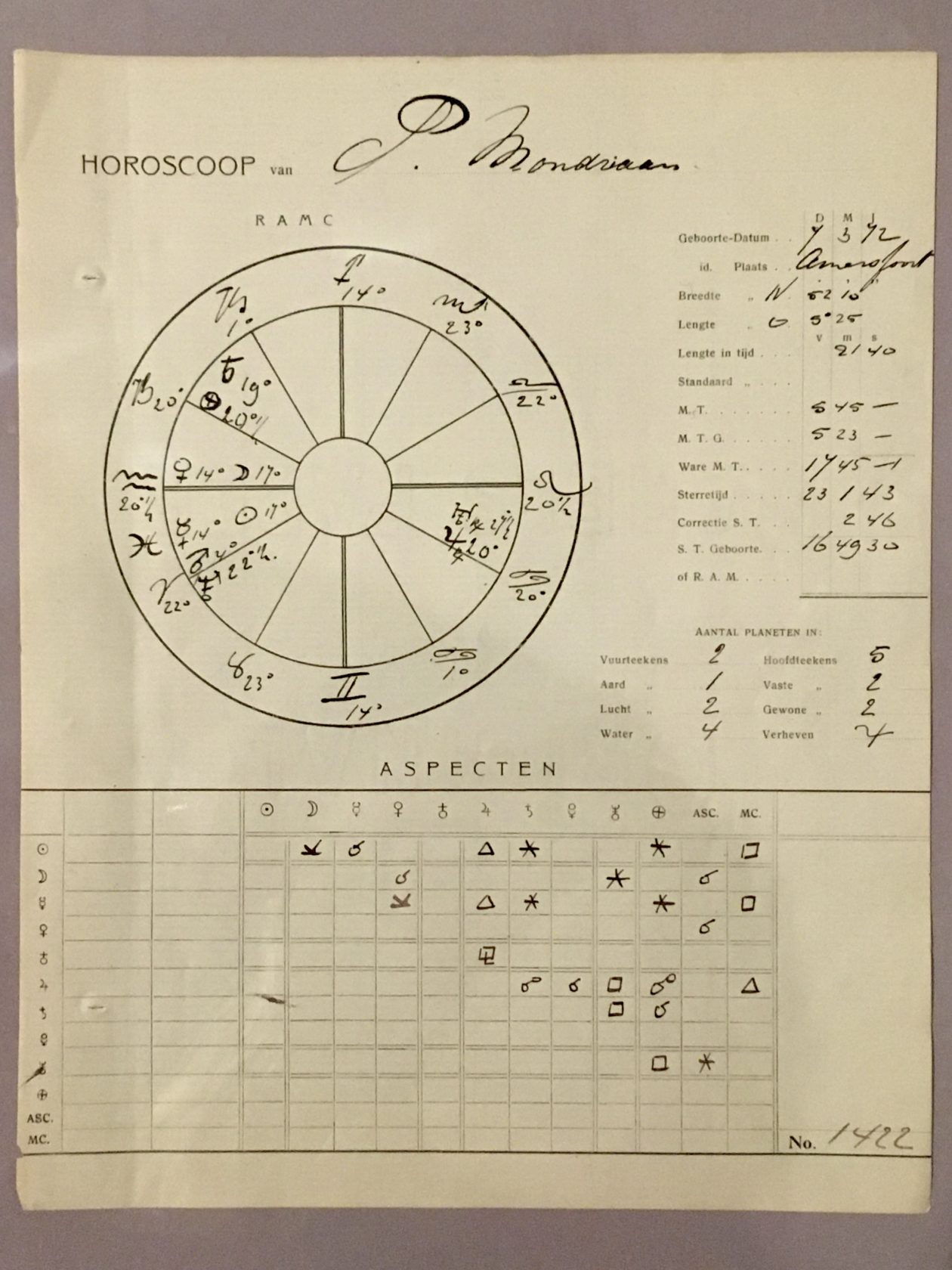

Both af Klint and Mondriaan harbored a deep fascination with nature, and strove to understand its workings through study, notation, diagrams, and scores. Under a glass case there are even letters from Mondriaan in which he waxes lyrical about his love for flowers, which I find strangely endearing (imagine writing to your buddy just to tell them how pretty flowers are!).

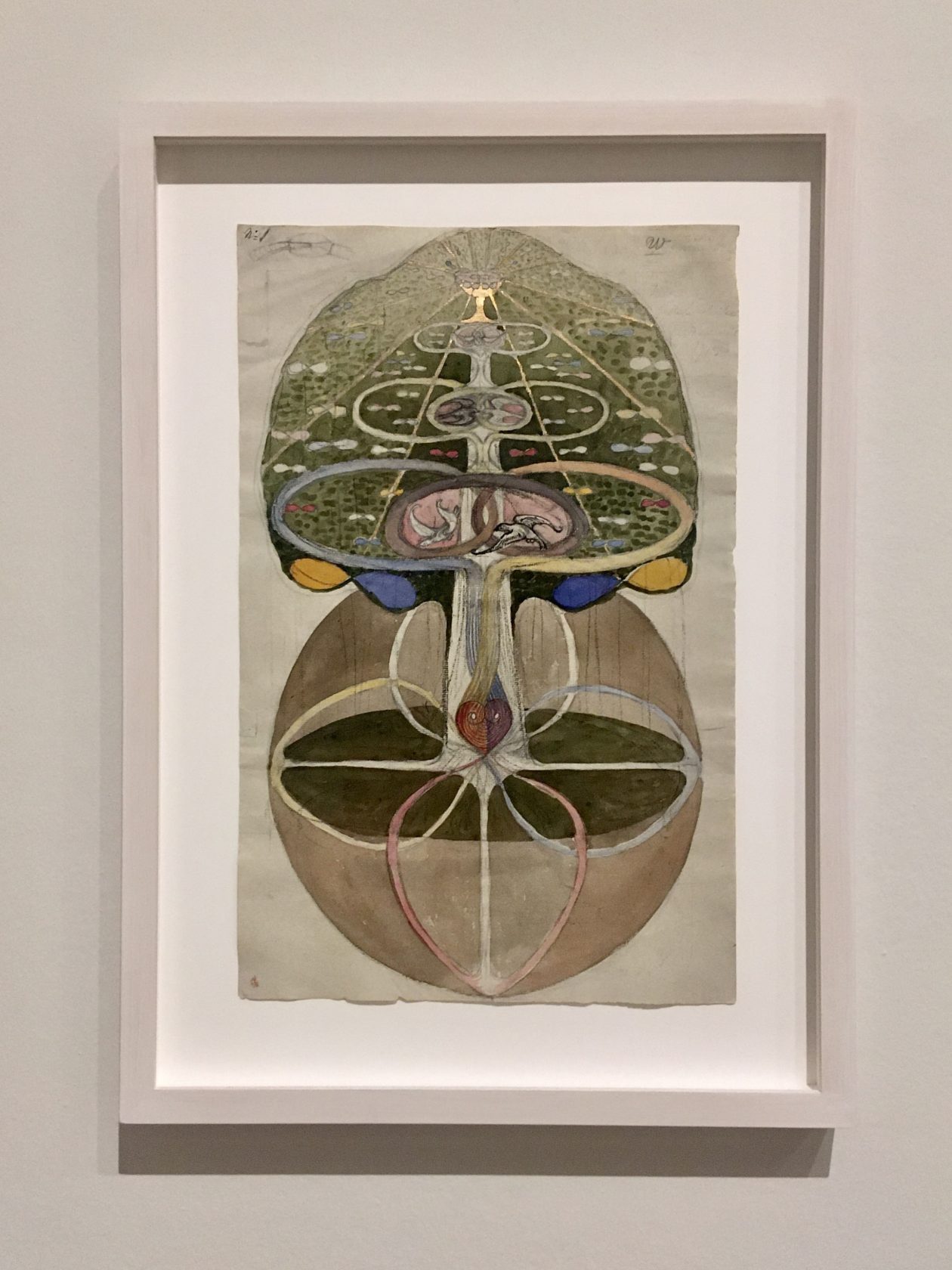

Each was active at a time when new technologies such as photography, radiography and the microscope were coming to the fore, and revealing things previously unknown to human perception. This scientific advance fostered a kind of mysticism, a vision of the potential of human transcendence. Af Klint, working as she said, from the words of her spiritual guide Amaliel, sought to depict humanity’s ascension to a higher plane. She was part of a spiritual collective of four other female artists, who named themselves De Fem (who deserve a retrospective all to themselves like, yesterday), and together they studied theology and conducted seances. It was through these communications that af Klint was ‘commissioned’, as such, to create the monumental project Paintings for the Temple. In 1904 af Klint would join the Theosophical society in Stockholm. Five years later, Mondriaan would join the corresponding organization in Amsterdam.

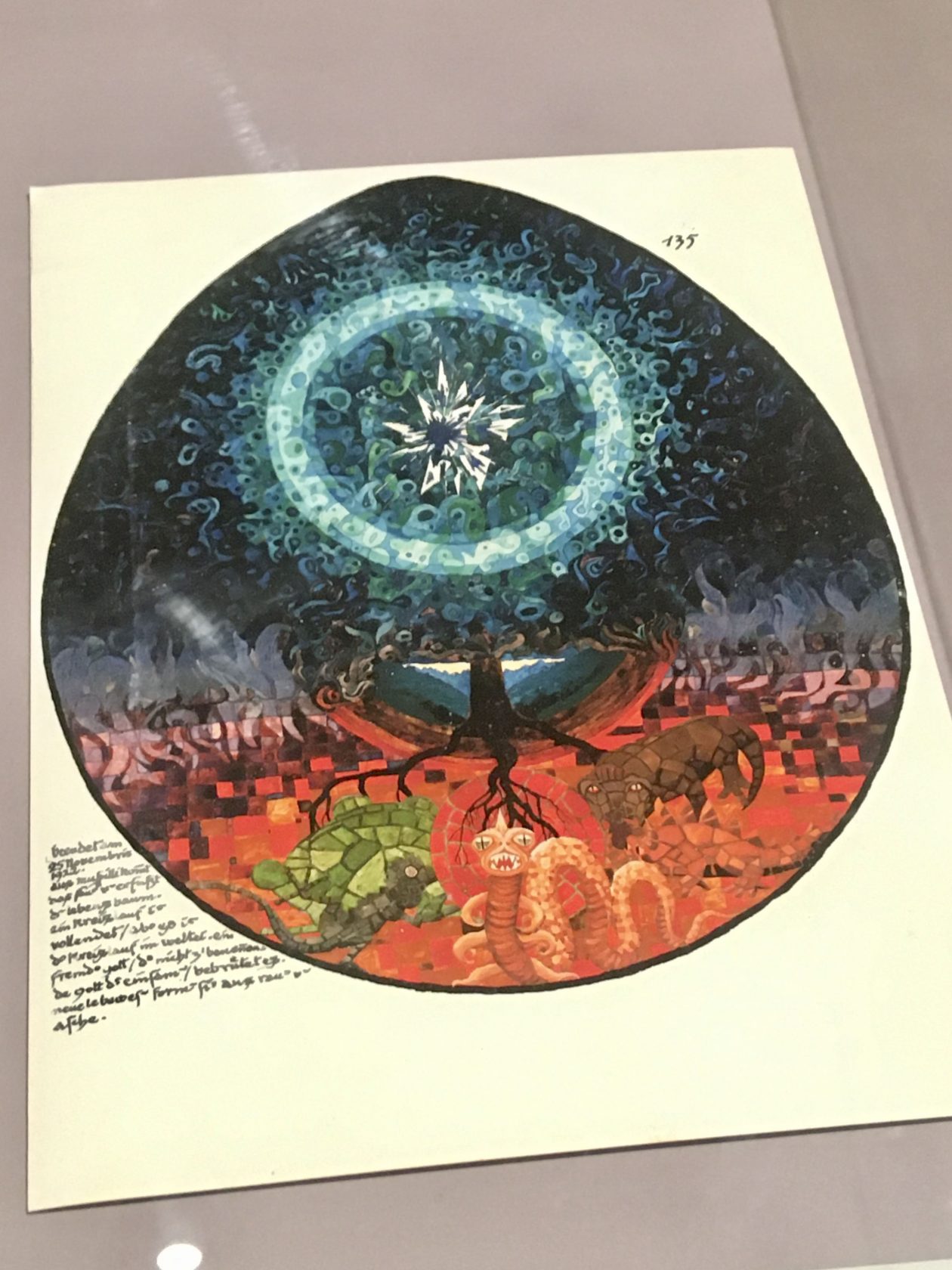

Mondriaan and af Klint’s quest for transcendence was not exclusive to themselves, however. The central room of the exhibition is named ‘The Ether’, and it gives a glimpse into the rumblings, vibrations, and circulation of ideas that were occurring amongst their close contemporaries at the time — from scientists, to philosophers, spiritual leaders. An item of note is Carl Jung’s Red Book, sumptuously illustrated — I hear a fellow visitor exclaim “I didn’t know Jung could draw!”.

The final leg of the exhibition displays both af Klint and Mondriaan in what we might call their final forms. It is the very different results of a similar effort to transcribe, and make visible, the laws of nature. The flowing, vegetal forms of af Klint’s work are a world away from Mondriaan’s geometric slashes, but both originate from a need to produce a score that makes playable the intangible forces of creation.

Af Klint’s Ten Largest adorn the walls of the last room, the journey from youth to old age displayed circularly, as af Klint foresaw in visions of her spiral temple. The size and soft grandeur of the paintings cloaks me with quiet reverence. You could spend a long time here in the gentle thrum of af Klint’s magnum opus, dimly lit and cool. I hope to again when she makes her way to The Hague in October. And I guess I’ll check out Mondriaan too.

‘Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life’ is at Tate Modern in London till 3rd September.

A similar show will arrive at Kunstmuseum Den Haag 7th October to 25th February 2024.