Unearthing the turf – Excavating KABK’s buried plaster treasure

A week before the KABK Royal Academy of Art’s Graduation Festival opens, Anastasia Loginova and Frits Dijcks (J&T) met up with Fine Arts student Robin Phoenix Whitehouse to talk about his fascinating project. Robin is rummaging around in the guts (and gutter) of the KABK, digging up the once legendary plaster collection which the Royal Academy was once proud of but which was then, in a stint of revolutionary angst, smashed and buried in the 60s. Some of the collection was picked up by the Allard Pierson Archeology Museum in Amsterdam, some was taken home, most was smashed and buried literally underground today lining the soil of the academy’s basements, with no aftermath. We decided to investigate.

Robin: “Last year while on an exchange in Paris I met a professor, Mick Finch, who was talking about how art institutions deal with their collections. During the 1900s all European art schools had large collections of plaster (gips) models for study purposes. This professor mentioned, in passing, how students of an art academy in The Netherlands had smashed and buried their plaster collection during the 1960s. It caught my attention and I asked the professor which art school he was talking about, he told me it was the Royal Academy of Art The Hague.”

So you heard about it in Paris? (Frits laughs)

“I heard about it in Paris from a professor from London who was visiting Paris doing a talk. I was sitting there in the class and he was talking about this school in the Netherlands. I was like which school? He was like, the Royal Academy of Art, they just smashed it and buried it in the courtyard.

“I was fixated with this romanticised idea that buried somewhere was the smashed plaster collection that had been disposed of in the 1960s. I just started exploring around the school and thinking where it could be. I had this idea that there’s just tons of plaster sculptures buried and I want to find them.”

“Now we can go to the basement.”

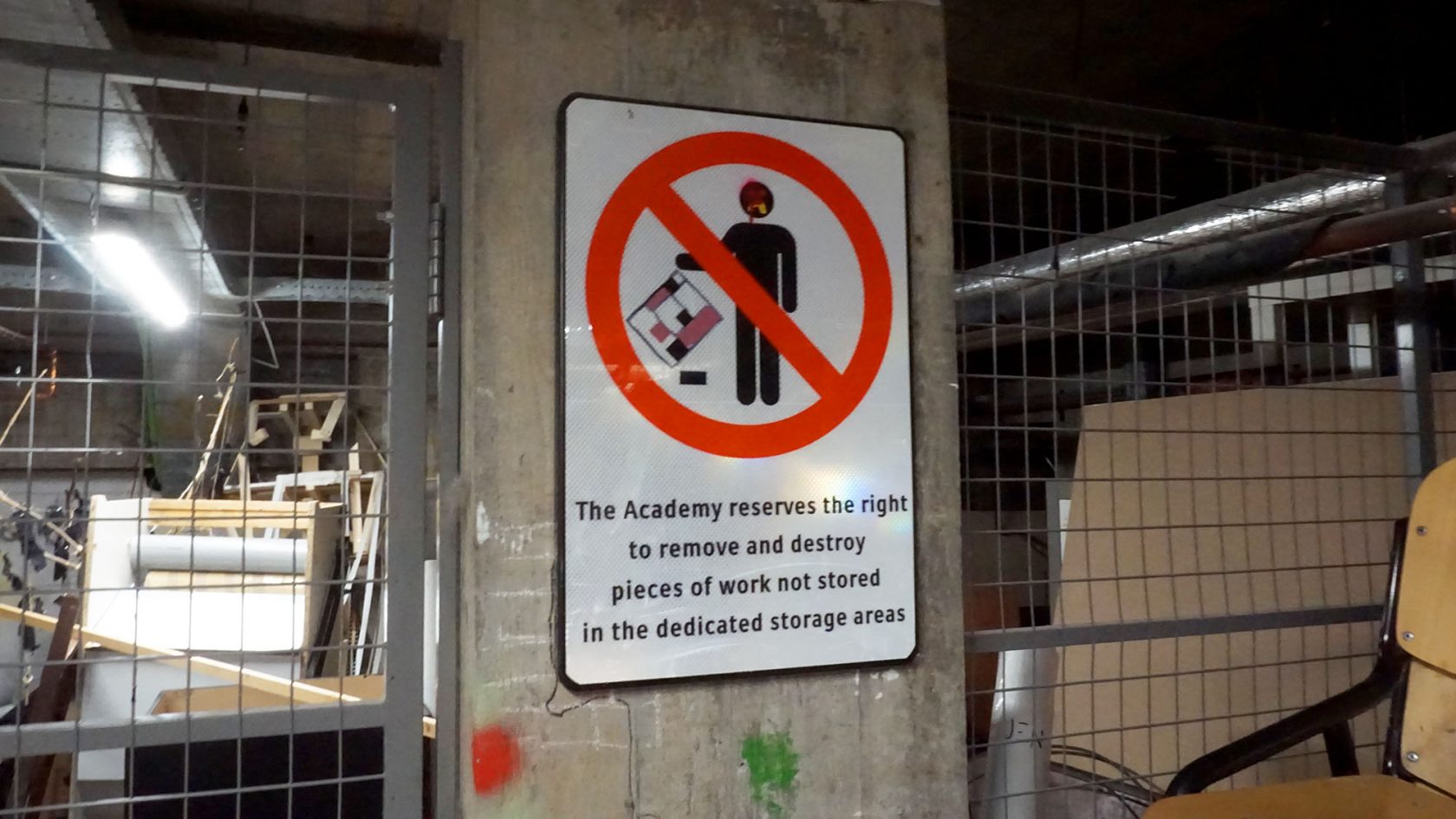

“I was waiting here (points at a space outside a locked door in the basement ) for people to not be passing so I could investigate the wooden board and go behind it. At first I did not tell anyone but then the school facilities staff got a bit suspicious, they thought I was doing graffiti or something as I was always down here in the basement.”

So first you didn’t ask anyone, you were just doing your own thing?

“Yes, because if I told them, it would not have been taken well. I had to collect some background information first.”

Why do you think it wouldn’t have been taken well?

“Because it would be a semi-naive approach like, hey, I want to have a look in this basement for something which may or may not be there, maybe I’ll take some pictures. So first I gathered information from talking extensively with a lot of people outside of school.”

“Once I had a case and reason, I talked with them, but even then the facilities said that at first they were going to say no, but based on what I told them it was already one step ahead. This was very much something I had to set up.”

Can you tell us a little bit about yourself, your practice? What is it that you do?

“Yes it’s about being aware of or addressing my presence in place and time, like with my previous work ‘The Rock’, for example which was very much about using the rock to make a happening in time and space as opposed to being about the object itself. It’s about being in these situations that arise from it that is the interesting part, as opposed to the sculptural object or painting itself.I like to work on projects that are shaped from interactions and relations. To be immersed within the surroundings and context, which in this case is archaeology and stories around The Royal Academy of Art The Hague.

“My project is about addressing my position in this place and time in which I will graduate. In uncovering and looking at the history of the institution I feel it gives the audience a new way of relating to aspects of the institution by understanding its history. I feel that it is my responsibility as an artist to share this story in order to appreciate and look in a different way at our surroundings. My time in the academy and my education has been shaped by the events that took place in the 1960s, and I want to share this missing puzzle.”

“The KABK have the Gipsenzaal that they pride themselves on but there is nothing actually, no records that they have about the infamous ‘Beeldenstorm’ of the 60s, which is a huge part of the school but which is completely buried underneath, like it did not happen. You can see here they have literally dug holes and buried the plaster underneath the offices of the administration and finances.”

Who was doing the burying, the students or the staff?

“They still don’t fully know in what way it all took place, I’ve been told by former students that they smashed it. Also that it had something to do with the Dutch IRA. This is what the professor from London told me. It was a kind of wave of revolution and change, there were parallel situations in France, Germany and the US”

“Buried beneath the ground and scattered across the soil are tonnes of plaster fragments, details from architectural reliefs, hands from classical Greek sculptures and piles everywhere of smashed plaster sculptures lying like a graveyard of a former museum. You eventually find that there are lots of pieces from what would have been one object so you can imagine that everything is here. It’s really an archeologist’s dream to find everything in one place and it was just smashed 50 years ago so it is still very recent.”

Do you now see a career in archaeology?

No, I’m not an archaeologist at all. I’m an artist and I will be an artist. But I do enjoy playing the role of being an archaeologist for a bit. I’ve told stuff to the Allard Pierson collection, which they did not know. For example they did not know that this was here. They were like: how has this been kept secret for all that time?

When did you decide to make your graduation project?

“I had known for the last few years that I wanted to present a project that is specific to this space and time, something relevant to the academy and to somewhat stand back and look. This January, when I found this site was actually here and hidden underneath the institution, I just knew I could make a project out of it and share it. For the graduation show I will present this story. It is something that has not been addressed by the academy and is something that remains relatively unknown. There are small rumours that the students in the 60s buried the plaster collection but the fact that they have been smashed and buried under the academy is something that seems unknown to the institution and has never been brought up. I want to tell this story and to be able to share it with a wider audience, it is something that is in my opinion so relevant for the way that we view the institution and it has completely shaped the academy that we stand within today.”

Oh you are reconstructing pieces! Wow!

“Working like an archeologist, I set up the basement with lights, large tables and began to categorise the findings, while keeping the discovery a secret from the academy and people above. After a few weeks of sifting through the sand and soil and piles of plaster I was able to start to piece together some of the pieces like a jigsaw puzzle. The pieces that I had been finding were made around the late 1800s as plaster copies of classical greek roman and gothic sculptures.Upstairs are all the reconstructed pieces. There are also bits of hair from busts, eyes, heads. Most parts of a lot of the figures are still here.”

What is the feeling of putting the pieces together?

“It feels strange. They have been valued as broken but still kept on site, so it’s satisfying to see them back together. For example the circle is 360 degrees and you’re missing a piece and you know it’s there, you’re literally digging, like I know this, this is what I need, and then after weeks you find it and it just fits perfectly! The smashed pieces tell the story so blatantly. When they are back together it shows the biography of the object and how their destruction in the 60s is such a solid act.

Are all the pieces you are showing on display excavated from here?

No, some are on loan from the Allard Pierson Collection. When the students were smashing them in the 60s, the Allard Pierson collection sent a van to the Hague on time, to save the classical figures. The three figures on display and the head of Zeus were preserved and are now back here on loan.

They were here originally and are now brought back from Amsterdam?

“Yes, so they were brought from Amsterdam. I had to do a formal loan request and the art handling company Hizkia Van Kralingen transported them here. It’s funny because when they were taken from here originally in the 60s, Allard Pierson collection just chucked them in a van with no paperwork and drove them to Amsterdam but now the procedure is very different. You could argue that they still belong to the academy as there was no formal acquisition of these for their collection. The whole procedure to bring them back has changed so much in the span of 50 years. Now they have to be insured, specially handled and specially packed. 50 years ago they were in a basement, just chucked there. It’s also in the interest of the Allard Pierson to have them on display on their original pedestals and place. They were originally also here in this room. All of these rooms (the Galleries) were one large Gipsmuseum of the school. The Library and Computer room also.”

“KABK is not aware of what they have, what still belongs to them, what they lost along the years. Even now they are not fully aware that it’s all underneath the school and they are not aware of these pieces that have been reassembled and are, in effect, museum quality.”

What do teachers or professors from your department say about the project?

“I’ve kept the project quite secret because for me the element of surprise, which comes with secrecy, is important for my practice. It’s more exciting. I spoke to some who studied here before and they related in a certain way. They were in the institution in the middle of this transition. Some others just found it exciting to go into the basement and see, there is a buzz to it. I like sharing this excitement of discovery.”

You have the new generation of students and the old generation of students, which is very much related to the situation that is happening now at the academy. Do you see a parallel?

“It’s quite interesting when I spoke with facilities. There is a parallel about what’s happening now but now the way we are putting our voice out there is, well it’s just like putting some paper posters on the wall. It does not have the same power and courage. Before there was a revolution.”

There was a sleepover?

“Yes, okay, there was a sleepover until midnight. I suppose it was kind of cute. If you picture what they did in the sixties in today’s terms, it would be like smashing the Hack Lab, smashing the computers, taking over the websites, taking over the Instagram accounts. Taking over the TikTok account – that’s like smashing the whole thing.”

I think it’s very interesting that you had the curator from the Allard Pierson meeting here with the KABK. You’re actually bridging worlds.

“Yes, he is a curator in his 50s and I introduced him to the current governing body. I was like this is so and so, and this is so and so, they shake hands, they have your stuff in their collection. For me the relational aspect of this project has been crucial; bringing people together, gathering information from various sorts of people, everyone I have talked to so far, who have generously shared and contributed their stories, the different angles and perspectives I have had to take to negotiate on behalf of various institutions, this has all been a fundamental part of my research, a sort of social sculpture so to say.”

“For me the relational aspect of this project has been crucial; bringing people together, gathering information from various sorts of people, everyone I have talked to so far, who have generously shared and contributed their stories, the different angles and perspectives I have had to take to negotiate on behalf of various institutions, this has all been a fundamental part of my research.”

Also aesthetically, this project communicates quite differently to most of the other works which are on show, this relates to classical sculpture and perhaps will communicate differently to an audience who also want that.

“Yes, this is a textbook idea of fine art sculpture, when I was 10 years old I would have imagined these classical greek figures if someone said sculpture. A kind of notion of what we may think of “fine art”, large plaster figures and busts displayed on pedestals.

There are a lot of people on the street who have absolutely no relationship to what they see here or there (pointing to other works), but this will make them happy. Get these people in.

“Some proper sculpture. Real sculpture.”

Is that how you feel actually?

“Not really, I mean I am kind of playing with the fact I graduated from sculpture by looking at the notion of sculpture. They are something that is difficult to grasp, between class and wealth and reproduction, a part of the canon that sought to be smashed and taken out of the institution. It’s entertaining for me that if you google “sculpture” you find sculptures of figures like these, but for me I’ve put the focus on the story and how they can be related to. It’s entertaining for me that if you google “sculpture” you find sculptures of figures like these, but for me I’ve put the focus on the story and how they can be related to.

How revolutionary is the dream today? I think it’s really conformist.

“The root is the conflict between the young and the old at the moment. Then and now. There is a parallel.”

Yes, there is a parallel and because there’s a parallel, you made this project. Without if there was nothing going on around here, maybe this would not be not this sort of project.

“I am not trying to overly play with the conflict but the school is also there for us to play with a little bit. I think it’s very much that you can use the Academy, really use it, kind of not just that we are paying for an education, but to have a presence in it to do something. It is the “Royal” Academy but it sort of goes not unnoticed that we have the space and surroundings and people here. We should be aware of it and its circumstances and shape them how we can.”

You’re doing the patchwork, you’re repairing. It’s interesting, what do you hope to achieve with this?

“For me, it was exciting to discover this and to communicate the story, to shape a project out of these conversations that includes the institution, but more for the people around me and for the graduates from before that they can see and look at this school in a different way. I think it’s quite interesting. Something about an act or moment that leads us to look at our surroundings in a different way. Even when I’ve talked with graduates from two years ago or five years ago or 20 years ago, they do suddenly look at the school in a different way afterwards. It’s not like I’ve made anything or done something crazy. It’s just like, Yo, this is a little story, with it you can relate to the institution from quite a different angle and view now.”

You can see the project “Excavation of Gips Collection 1881-2023″ of Robin Whitehouse from June 30th – July 4th 2023 in Gallery 2 (originally the Gipsenmuseum) at the KABK Graduation Festival, Prinsessegracht 4 in Den Haag.