Death by landscape – insights on welding new worlds

The series of essays Death by Landscape (2022) was introduced by its North American author, Elvia Wilk, in a lecture at Stroom Den Haag on 17 March 2023. The lecture was part of the programme accompanying the Stroom Den Haag exhibition Positions: Elsewheres, and was organised by curator Lua Vollaard (Stroom) together with artist and writer Alice Bucknell at the Berlage Institute for Architecture and Urban Design at TU Delft.

Working in the cultural sphere, my daily life often involves questioning (and attempting to answer): how can we talk about the value of art as the world around us burns? In a short and refreshing lecture, author Elvia Wilk drew out some themes from her essay series Death by Landscape that go some way to answering this question. Both a writer and a trained artist, she argues that art and fiction have a responsibility to offer alternative worlds – worlding – setting out more sustainable and more equitable ways of being*, while challenging the narrative about who gets to tell, and be in the foreground of, the story of the worlds we live in.

With risk and innovation impossible in a capitalist system (she argues), fiction must ‘arm’ its readers with much-needed alternatives. These alternatives must avoid turning into hopeful, unrealistic utopias – rather acceptable dystopias. Though she ridicules those who say that pessimism gets us nowhere, Wilk struggled to articulate how worlding in art and fiction arm us for practical change in the dystopian worlds we live in everyday. Yet we heard that there is hope.

We shouldn’t think of worlding through a polarised spectrum of plausibility or utility. The worlds that art and fiction imagine may be untethered from our existing system of rules but the loop between fiction and reality is tightening. Fantastical doesn’t mean flimsy. Implausible doesn’t mean impossible. Fictional doesn’t mean far from reality. Growth doesn’t always mean progress. Imaginative doesn’t mean a lack of implementation. And, a central theme of Wilk’s work, the background always influences the foreground.*

So what does this mean for the practice of worlding? New to the term, I initially mistook the term worlding for its more applied cousin, welding. Might we consider instead how art welds different worlds together? The best bits of the worlds that we and others experience every day; the worlds in which crises unfold and solutions are needed; and the better worlds that we have the potential to create. Does this help us to manage our expectations of art’s purpose in our dystopian reality?

Wilk seemed to end by saying that it’s easier if we see art and fiction as tools of architecture and design. It brings us down to something tangible, to a place where we can imagine ‘reality-adjacent’ worlds in which everything* and everyone* get a say. Where small changes, welded together, might be at the same time radical and plausible.

*A note on the who and the we

Who do we mean by ‘we’? Our worlds differ remarkably from one another, particularly if you think in terms of geography, wealth, health and background. And what about nature, the water, the animals, the air, the insects, the background that influences our everyday life but doesn’t get a vote or a voice in the debate? They don’t have the same desires or agendas. Better worlds will be unable to meet all demands: a compromise will be needed. Even in the most utopian worlding, someone has to lose a little bit. This is where equitable, artistic worlding could help in the negotiation.

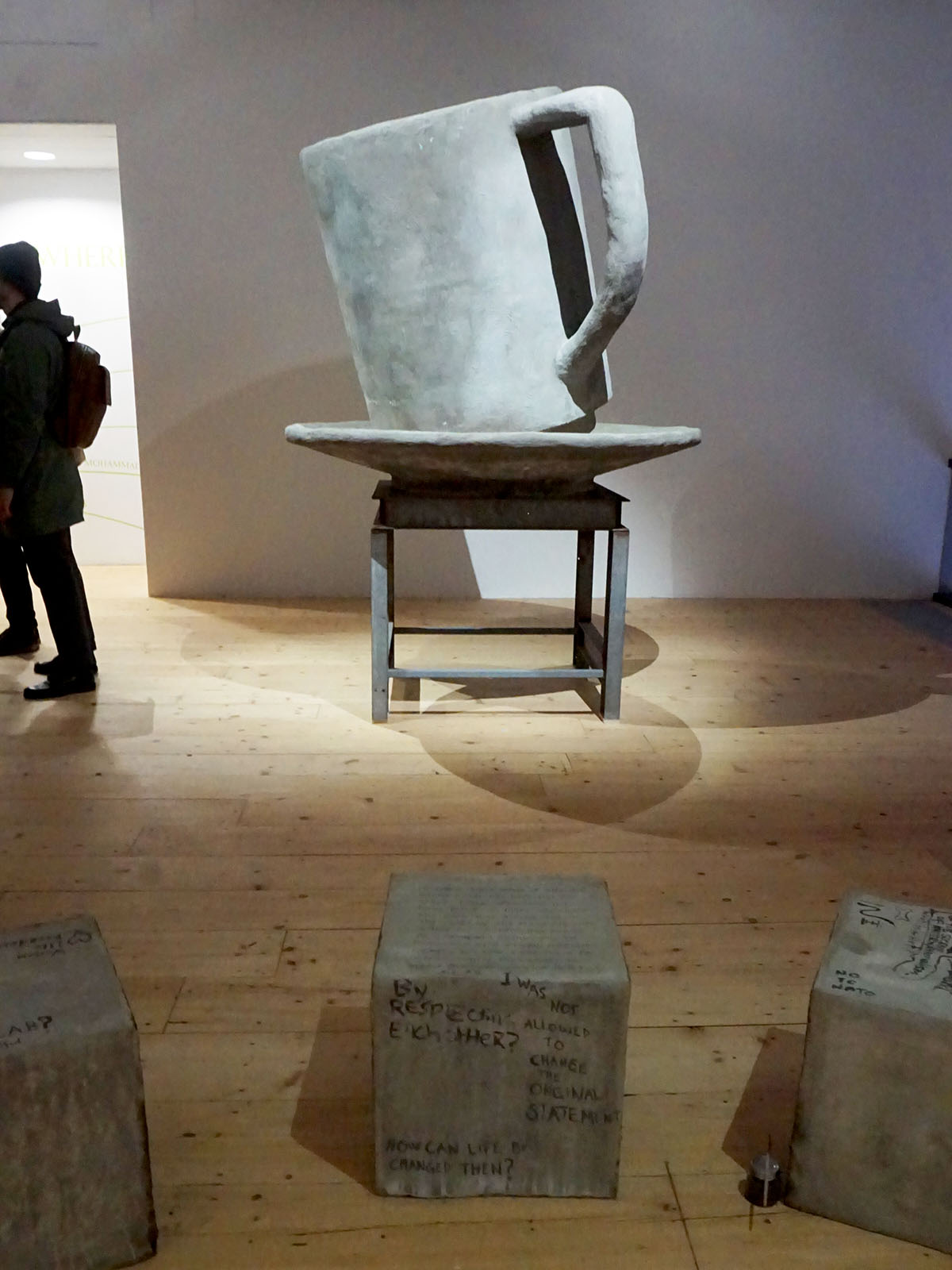

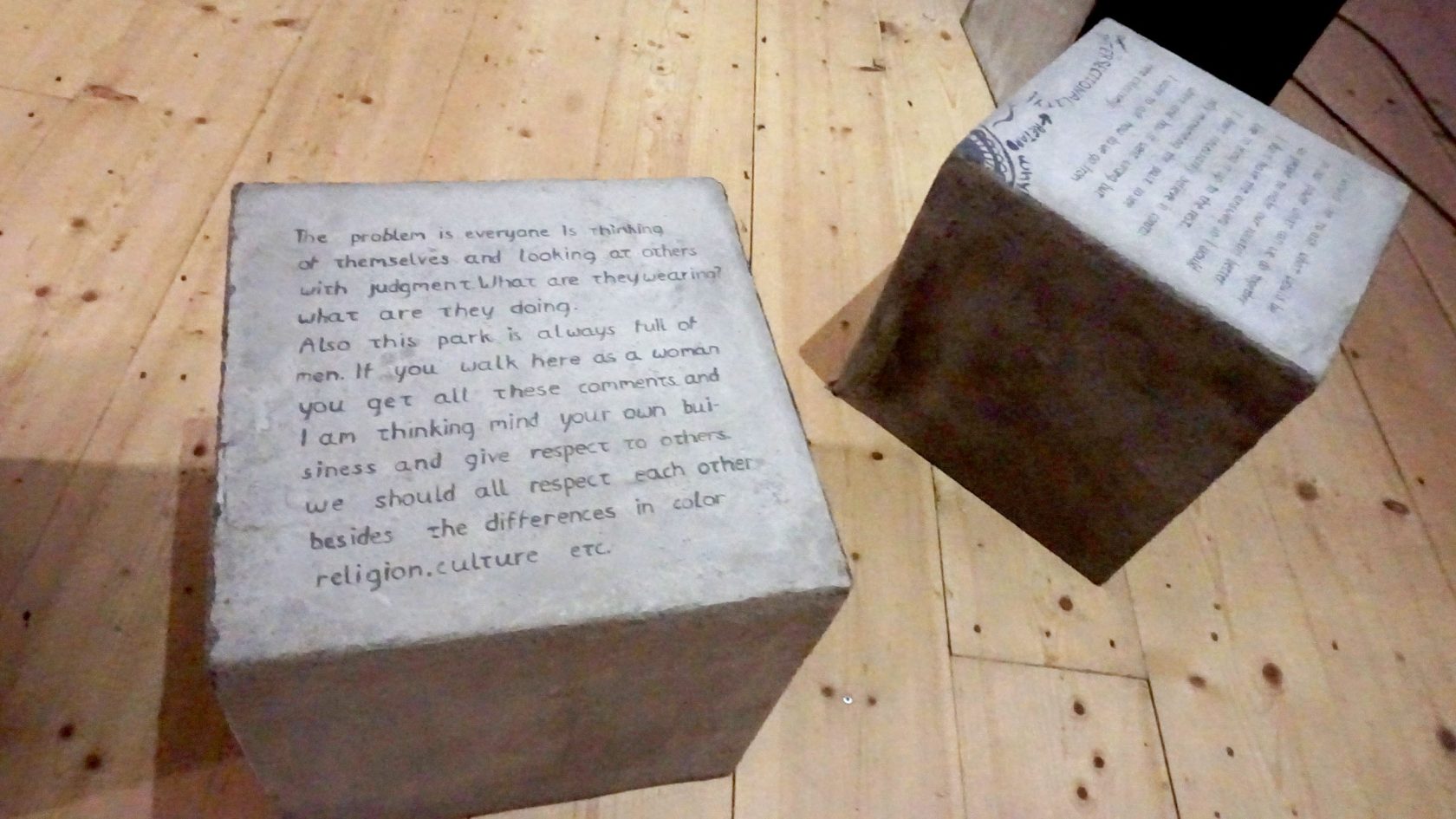

The exhibition Positions: Elsewheres is on shown until 2 July 2023 at Stroom Den Haag, Hogewal 1-9 in The Hague.

Images of the exhibition at Stroom Den Haag, taken by Frits Dijcks, Jegens & Tevens.