Stroom Invest interviews / artist Eline Benjaminsen

This summer we are tempted by an exotic trip, buy the latest mobile phone and organise BBQ’s with meat in abundance. To ease our conscience, we pay for the planting of trees to offset our carbon footprint. This is how the regular market works. We have a problem, so we consume a product that helps us. Debt is settled to ‘clear the conscience’. Eline Benjaminsen investigates and questions such socio-economic processes and how they affect our daily lives. She is looking for a visual language to gain insight into the complexity of economic transactions.

Born in Norway, Eline Benjaminsen (°1992) moved to the Netherlands at the age of 19 to study at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, where she has been living and working for seven years now.

Where does your fascination for socioeconomics come from?

Eline Benjaminsen: I’m interested in socioeconomics because it’s an elusive subject. It relates to the processes that take place outside of what we can sense around us, yet they completely define our lives. I’m trying to figure out what I don’t get in visual language because that’s the language I know best. It’s also the language that is very often missing to talk about these topics. Today’s power processes miss materiality more than ever, which is why they miss images. So, when these processes affect our daily lives, I think it becomes very important to look at them and make them visible somehow. I try to make them appear somehow, in order to understand what it is we are dealing with, to be able to address them. I challenge myself to give these processes a physical form through imagery. It helps me to know how to relate to them. I also hope that people can follow that story line with me in the making of my images.”

Our global economic system is not transparent and rather complex. How do you try to understand that?

Benjaminsen: “That will always depend on the topic. My graduation work ‘Where the money is made’ has to do with automatic, algorithmic trading. Here, profits are made at very high speeds. One thing that I did was to follow the actual trading route. The physical places where these microwave signals are transferred through the landscape, through huge satellite dishes. I also tried to access trading firms to understand the human perspective. I wanted to speak to people who write the codes and determine how these algorithms work. However, access to the financial sector is usually difficult. In the end I approached financial workers on the street in the financial district of Amsterdam. I asked them if they could explain to me and draw in the easiest way possible how high-frequency trading works. Everyone drew it differently, from quite technical to humorous drawings. I like that. It shows the difficulty of explaining and converting these abstract systems into images. Although the global financial system at large, of which this high-frequency trade is only a part, is very influential, no one has a complete overview of how it functions in its totality.”

How did you make this invisible system visible with photos, videos and installations?

Benjaminsen: “I started by photographing very mundane landscapes. You wouldn’t necessarily think of these places as somewhere that have anything to do with high finance, but you could say they are where some of the biggest profits are being made today. That’s why I think of these photographs as being perhaps mostly successful in their failure to document what’s taking place there. This contradiction is interesting to me. I made a zine, something between a photobook and an artist publication. I also like the idea that you can find it left behind on the train or you discover it at an art fair. Usually I exhibit the publications on the floor. I like that ambiguity in value, that it’s up to each person to decide if it’s a zine or a collectible art publication. I also made a short film of about five minutes, where I flew a drone following the microwave links of trading between transmitters and receivers. The mind experiment was if this flying object could interfere with the space where all these billions of orders are passing within.”

For your current project, you paid €11,25 to a company in London to plant a tree in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley that would compensate for 28 kg of your carbon footprint. Why are you paying for a tree in Kenya? It’s somewhat absurd.

Benjaminsen: “Exactly, that’s why it triggered my curiosity. After the purchase I received a certificate from the firm. It looks like a diploma, with my name next to the kilograms emitted and compensated for by that tree. I got fascinated by this new way of seeing viewing trees as products in a marketplace. How effective is this one tree in performing the services promised to me? How is it possible that individuals like me but also corporations and governments, can cut CO2 levels without having to reduce their emissions at all? I got curious to see how real this promise is. Because the only thing tangible aspect is the certificate. I decided to check if the tree was there. Who planted it and under what circumstances? I found the tree in an area outside of Nairobi, but it took a while to get there. The British firm did not want to refer me to the local organizer. They told me I hadn’t bought enough trees. I realised this is just one example of a bigger industry. There are so many companies doing the same thing. It’s impossible for me to say how successful this conservation project is and how it affects the local population. The people I talked with were happy with it, but they were all employed by the project. I also went to another forest, Embobut in the Cherengani Hills. There an indigenous forest dependent people, called the Sengwer, are suffering great injustices because of emission reduction programs aimed at opening markets to mainly sell offsetting services to governments in Europe. Norway is the biggest sponsor of these programs worldwide. These projects have shown to have quite dramatic consequences for people who have previously depended on the nature that is now being financialised. They are basically banned from using the resources adjacent to their houses farming or cattle herding and other livelihood necessities. Ultimately, it’s often a strategy for land grabbing, often viewed as a continuation of imperialism. Emission markets refers to the Marxist idea of the spatial fix. This means that as capital expands geographically, it is always rebuilt or inserted elsewhere. This of course is quite a common thing in globalisation. Emissions trading also relates to another Marxist idea of commodity fetishism. These are products of which you don’t know where the raw materials derive from, how they are produced, by whom and under what conditions. We only see the final product which is presented in the store. And with carbon offsetting, the success stories that are being produced which tell us, that this is a win-win situation for both the climate and local people around the areas that are being conserved, that final product is sold to the consumer.”

What will this project visually look like?

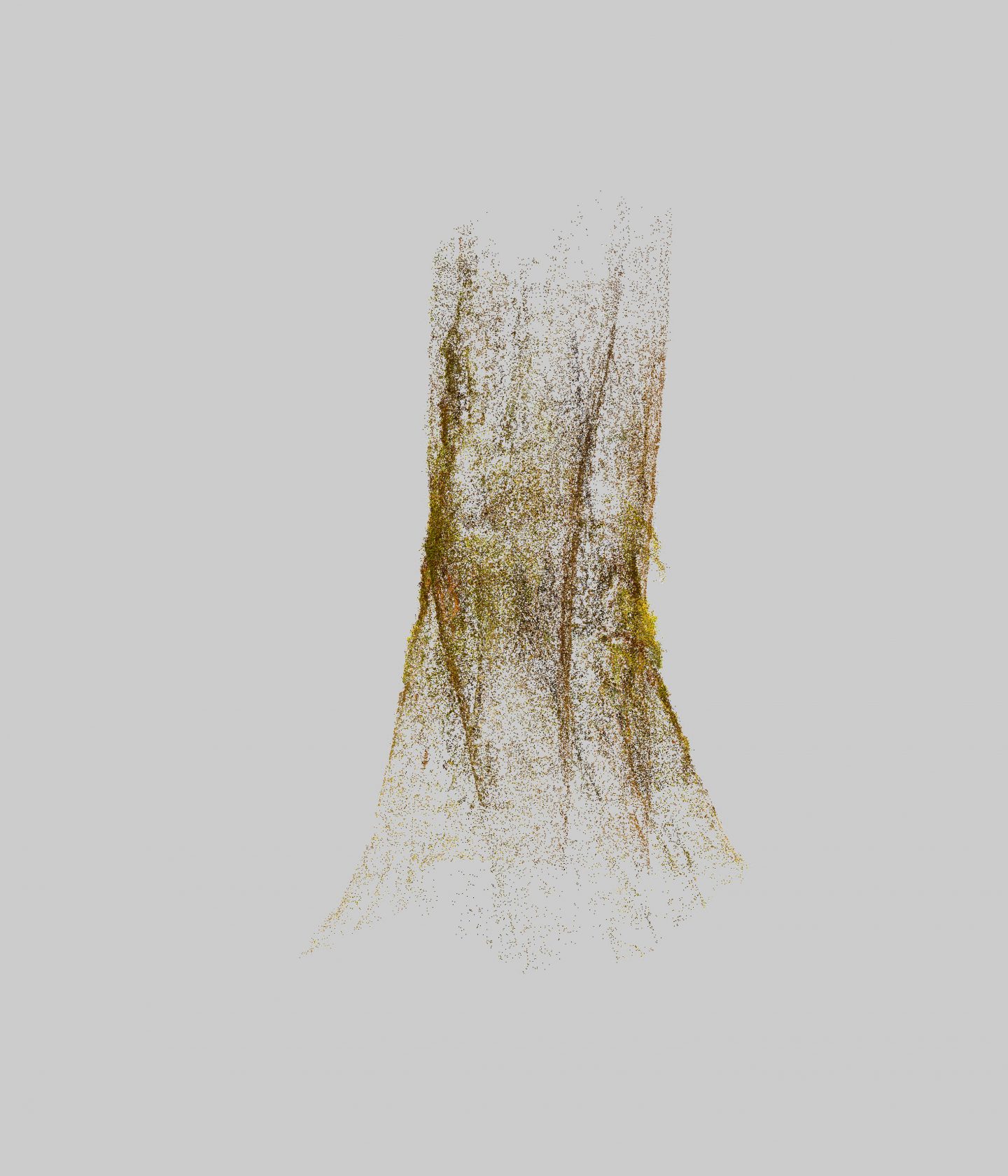

Benjaminsen: “I’m processing the material as we speak. I filmed, photographed, made photograms, recorded and wrote. These days I’m studying the imaging techniques and formulas that are used in determining how much carbon is stored in forests.”

“The world has enough for everyone’s need, but not enough for everyone’s greed.”, said Mahatma Gandhi. We would like to see nature grow in line with economic growth. Can more growth contribute to a better life and more happiness for the rich countries? Have we become greedy?

Benjaminsen: “The big problem for me is that we try to use the ‘logic of capital’ to solve our problems. Which is illogical because it is literally the cause of the problem. I find this a very interesting contradiction. We can’t continue to find market solutions for every problem. I think growth-based solutions will always have a problematic, exploitative side.”

What is value?

Benjaminsen: “Well, while my work is about economic value, looking at it from a market perspective. I think in doing so, it asks what it is we really value. You can say that it is market logic that shapes what is valuable and what is not. I often think that what that dictates, is quite absurd. In my personal life value equals a community, care, being in nature, feeling safe, being allowed to work on the things I find important and good books.”

The corona crisis has made the rich even richer and mightier and the poor even poorer. Inequality is increasing.

Benjaminsen: “The Canadian writer Naomi Klein is talking about what she calls the shock doctrine. It’s about the idea that during crisis governments often implement new legislation that benefits the most privileged ones. That’s why it’s extremely important, also during crises, to keep studying the ways these systems run.”

This crisis exposes once more the structural errors of the dominant economic system. Adjustments seem warranted. As an artist is it possible to initiate an awareness with your work?

Benjaminsen: “The journalist Joris Luyendijk talks about taking your readers with you in the process. Start as a beginner, as someone who doesn’t understand what you’re about to research. Economists often use jargon when talking about these things, while as an artist I use a different language. I start as an amateur and gradually expand my knowledge while my project takes shape. Another important aspect is the place where I show my work. Besides galleries, art spaces and museums, I also want to present it in spaces where audiences unfamiliar with art can meet the work. For example, I would love to show my work in some place like the World Trade Center and have conversations with people there, or in shipyards and in financial newspapers.

I don’t believe that I can influence how economical processes work, but hopefully I can influence a few people’s thinking understanding through my work. That we can think together through these processes and relate ourselves to them through imaging. Images are strong, they move through the mind. I believe in this kind of chain reaction, where one idea causes another and so on. I think that’s a nice thought, that my images can be part of that chain.”

The Invest Week is an annual 4-day program for artists who were granted the PRO Invest subsidy. This subsidy supports young artists based in The Hague in the development of their artistic practice and is aimed to keep artists and graduates of the art academy in the city of The Hague. In order to give the artists an extra incentive, Stroom organizes this week that consists of a public evening of talks, a program of studio visits, presentations and a number of informal meetings. The intent is to broaden the visibility of artists from The Hague through future exhibitions, presentations and exchange programs. The Invest Week 2020 will take place from 21 to 25 of September.