Stroom Invest interviews / artist Gabey Tjon a Tham

Gabey Tjon a Tham is a “total installation“ artist. In her practice, she researches nature in relation to complex systems and technology, with the human only being a part of a larger ecological system, rather than on top. We spoke together about these thoughts being amplified and echoed by the pandemic we find ourselves in.

Cathleen Owens: Was becoming an artist a natural path for you?

Gabey Tjon a Tham: I grew up with music, playing the violin and the piano. This musical background influenced how I see and experience the world. Visual things have rhythms and patterns, while sounds have colors, textures, or forms.

I attended the art academy at ArtEz in Zwolle with the intention to study illustration design. But I soon realized it was hard for me to work on assignments if I didn’t personally relate to the topic. I wanted to tell my own story instead of telling someone else’s story. I started my second year in Fine Arts in the Hague at the KABK. There I expanded on my experiments with different media and noticed that the space around my work became a part of the work itself. I have a revelation that how a drawing is hung in a particular space influences how you experience the space itself. At museums I was most intrigued by the technological based art pieces that involve audio and visual elements, so that’s how I wound up at ArtScience. I took an introduction to sound course given by Robert Pravda and Geert Oddens. It opened up a whole new world for me: how to listen to our acoustic environment and describe the sounds that we hear, how to record them and make a composition. Sound is both a physical and mental experience that involves the whole body and not just the ears. The physicality of sound influenced the works I have made since then. Looking back, ArtScience was where I felt most at home.

On your website, you call yourself an installation artist. What does being an “installation artist” mean to you?

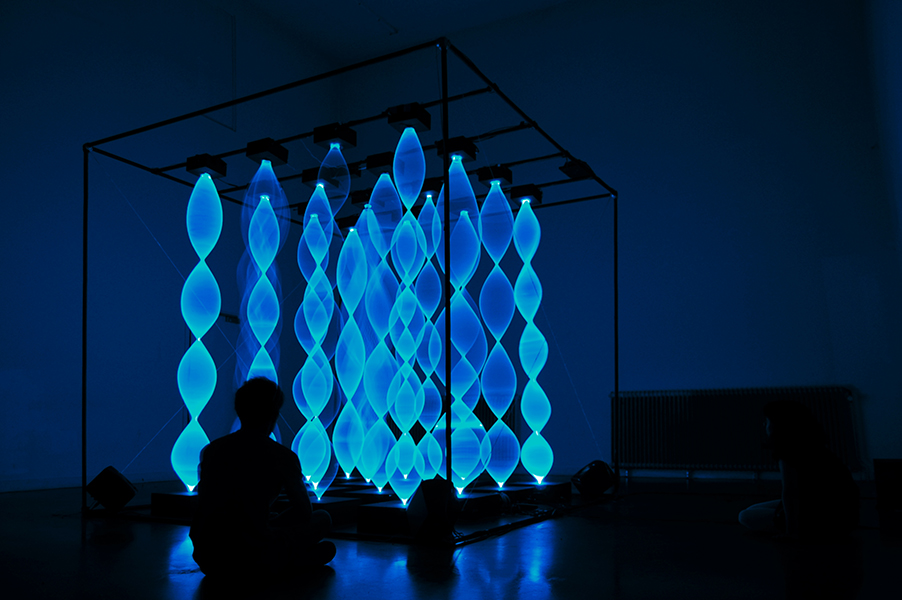

I make installations that transform a physical space into an immersive environment. According to the Russian/American artist Ilya Kabakov, in a “total installation” a new reality is created for the viewer that shifts his experience of time and space. It’s like a painting where you allow the viewer inside, where the border between the artist and the audience dissolves. A memorable comment someone made about my work was that she experienced it as being in a physical virtual reality.

It’s been interesting getting to know your work online, when a large part of your work is about the in-person experience. Do you consider one way of approaching your work is better than the other?

Many people get to know my work by seeing photos or videos of it. It’s two different experiences because online, this visual-focused way of looking at things is emphasized. If I would make work that doesn’t look so great in photos, I probably would have a harder time being invited to present them. It’s not that I make visually pleasing work on purpose, I focus on how the form and content can be communicated in the clearest way.

With making sure you’re communicating clearly, are you very intentional with your documentation?

I often ask others to document my work. Most of my energy goes into the realization of the piece itself which makes it hard for me to take a step back as an observer. I’m fortunate that the people I’m working with have been great at translating the physical experience into the documentation.

How has your practice changed with the coronavirus pandemic?

The main project I’ve been working on is a commission for a new work by the art space Tetem, in Enschede, for this year’s fall. Due to the coronavirus, I have to completely rethink my presentation form as a physical presentation won’t be possible. Even though museums can now open for the public, it’s not possible for all spaces to follow the guidelines. So I have to rethink my artistic vision and practice. At the same time, everything I have been making so far this year, only reveals its qualities to the eye of a camera, something that the human eye cannot perceive. I’d like to think of that as an organic change. But I can’t say the pandemic isn’t disruptive. For more than 10 years I’ve always been working towards an installation that transforms an entire physical space. This restriction creates the opportunity for me to explore the digital space and how our bodies relate to it. I’m curious how this new direction will affect my future installations.

What was your plan for Tetem?

The work will be a continuation of my research about technology and time. Since algorithms are omnipresent in modern digital technologies and intertwined with our daily lives, they co-construct the lived human experience of time. How can we cope with this change in perception of time? The algorithms that are present in our society do not originate from the lived experience, but are optimized for exponential growth and as such ignore human-unique qualities and everything that is not standardized. Algorithms can be seen as cycles or multiple cycles within a bigger cycle. The cycles have different time mechanisms that define how fast the steps are taken to reach a goal in precise and measurable programmed units. To me this resembles the rhythmic structures of computer processes that are in a continuous change.

To find a more equal relation between human and digital temporalities I’m exploring models from science that could possibly represent this non-linear and fragmented time in an abstract way. For example, to Einstein there’s not a singular time but a vast multitude of them: innumerable clocks with a different rhythm for every point in space. Another physicist that I am inspired by is Carlo Rovelli. He says that human beings are anchored to the flow of time because of entropy, where order dissolves to chaos through heat. Our thoughts create heat in our neurons. We can order the past but the future is always disordered. In physical reality time doesn’t have a clock with a before or after.

For the past months I experimented in my studio with water as a possible chaos element to reveal digital processes or disrupt rigid systems. Water as a physical fluid but also the concept of fluidity as a manifestation of itself in a mechanical apparatus or in the digital realm.

What does an average studio day look like?

My practice goes in waves. Some periods are productive and others reflective, depending on the different stages of each project. In a normal situation I mostly develop new works during residencies where I do the prototyping and realizing. In my studio I prepare for exhibitions that also involve technical improvements of existing works or I’m brewing on new ideas. I usually have a plan of what I want to do in the studio on any given day. The longer I am doing this, I’ve realized that as an artist it’s essential to be organized, which can be contradictory to what people assume. I am working now with an intern so I feel even more responsibility to be organized because I have to delegate tasks. Being an artist is not only about making things, but also about creating the conditions that enable you to continue to do your work.

To me, your work seems to be dealing with order and chaos. Are these elements reflected in your practice as well?

I consider nature as chaos and human behavior as the desire to have order but never being able to completely attain it. My installations are controlled algorithmically with custom-made software where the physical entities seem to move freely within a system of conditions. The emergent behaviors that arise reveal structures that can be interpreted as human, mechanical, or animal: a dance that excites attraction and tension between the entities and the observer. Chaos and order derive from the interaction between the physical and the digital. I often work with my material not how it’s supposed to be worked with. I consider the material to possess a nature in itself.

How do you procrastinate?

Procrastination is part of the artistic process, as you can’t be productive all the time. If I’m stuck with something, I find it helpful to talk about it with fellow creatives. Or anything else that doesn’t have much to do with my practice, going to a different place, cleaning my studio, sorting out components or my administration. Order makes me calm as it creates space for new thoughts. During the quarantine I’ve been binge watching the news obsessively because I feel it’s a surreal time that we are living in. The pandemic confirms that human beings are not the most dominant species on this planet. It makes us aware that we are vulnerable and part of an ecosystem in which all is entangled. I find it fascinating that a primordial lifeform like a virus can disrupt the foundation of society in a visible and invisible way. It doesn’t make a distinction between different kinds of people, but sees a human being as a population that consists of billions of cells.

The virus demands us to take a pause, in every aspect of our lives. That is also a crucial condition for my practice, to have a lot of time. I enjoy working on long term projects. There is a lot of research involved, not only theoretical but also technical and artistic. The development process is an important thing in my work and something that I want to emphasize more in the future by finding more ways to share it with others.

You write that we have to relate to technology as a new nature. Could you talk a bit more about that?

Nature is no longer visible in its romanticized view that has been heavily influenced by culture for centuries. The quote by Heraclitus: ‘Nature loves to hide itself’ resonates well for me in this, but also gives space to speculate what can be understood as nature. I consider our modern technological systems as a kind of nature as they become increasingly complex and untamable. I explore a perspective on technology beyond being an efficiency tool or an expression of power. I’m looking for a common ground that connects the natural sciences, technology, and humanity together. Something more nuanced and poetic where the natural and artificial, the human and non-human are balanced.

Do you consider your work political or would you stay away from that word?

All contemporary artworks can be considered political as they reflect on the current world we are living in. I see technology as a reflection of human behavior where certain traits are amplified due to specific technologies. Every technology in history has its own advantages and disadvantages and it’s up to those in charge to decide what to do with it, although users have a role too. My work creates spaces for reflection on technology as well as on our own place in the world and our relation to other species. I feel a necessity to amplify a female voice towards what technology can be, and that is certainly political.

What is your favorite or most inspirational place in The Hague?

It sounds very cliche but I like to go to the beach and the dunes. Every time I go there, I see new things. Even if I’ve been there many times, I see changes.

The Invest Week is an annual 4-day program for artists who were granted the PRO Invest subsidy. This subsidy supports young artists based in The Hague in the development of their artistic practice and is aimed to keep artists and graduates of the art academy in the city of The Hague. In order to give the artists an extra incentive, Stroom organizes this week that consists of a public evening of talks, a program of studio visits, presentations and a number of informal meetings. The intent is to broaden the visibility of artists from The Hague through future exhibitions, presentations and exchange programs. The Invest Week 2020 will take place from 21 to 25 of September.