Meet iii-resident Joana Chicau

Joana Chicau is designer, researcher and coder, who frequently pulls from her background as a classically trained dancer. We caught up over Skype to talk about her live coding performances and how they fit into the world we find ourselves in.

Could you tell me a bit about your background and how it impacts what you make today?

I started dancing ballet when I was five years old and I continued with this classical training until I was 18 or 19. At that time, I started to become more curious about contemporary dance practices, and other styles of dance. Around the same age, I began studying graphic design in Porto. At first I was mostly interested in printed matter but I started to become more curious about the role of graphic design in digital mediums. I guess it was the fact that I had these two threads going on in my life, choreography and design, that made me curious about their intersection and what I could learn from each side and by eventually merging them. This is what I explored with my master’s thesis at Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam. I was looking into choreographic scores, mostly from post-modern dance and simultaneously looking at scripts that you would use for web design and for coding online. I was interested in how those languages are structured, and how we name certain elements. Both of them are languages that are assigning instructions on either how the body or a piece of information should behave. I was curious to understand the common features but also the ways the two worlds contrast.

Using these two different languages, choreography and coding, in what ways do they contradict each other?

I think what’s interesting about the dance world is that people understand space and time around them as a material to play with. Time and space are set but a common goal is to disrupt or find new ways of working with them. Most choreographers understand movement as the thing that creates time and space. There’s a lot of agency in that and also a lot of freedom in how you use it. When you create a web environment, you are also setting up a certain time frame for the experience. You are defining a space for people to access that experience and there are many set standards in that. You mostly follow user interface default settings. While in choreography, you’re expected to challenge those assumptions and standards that you find yourself in. There are different attitudes. But of course, we are talking about different practices that operate in different ways, so that makes sense. You can see clearly where the friction is.

To what extent does rehearsing play a part in your practice? And does a performance function as a final result?

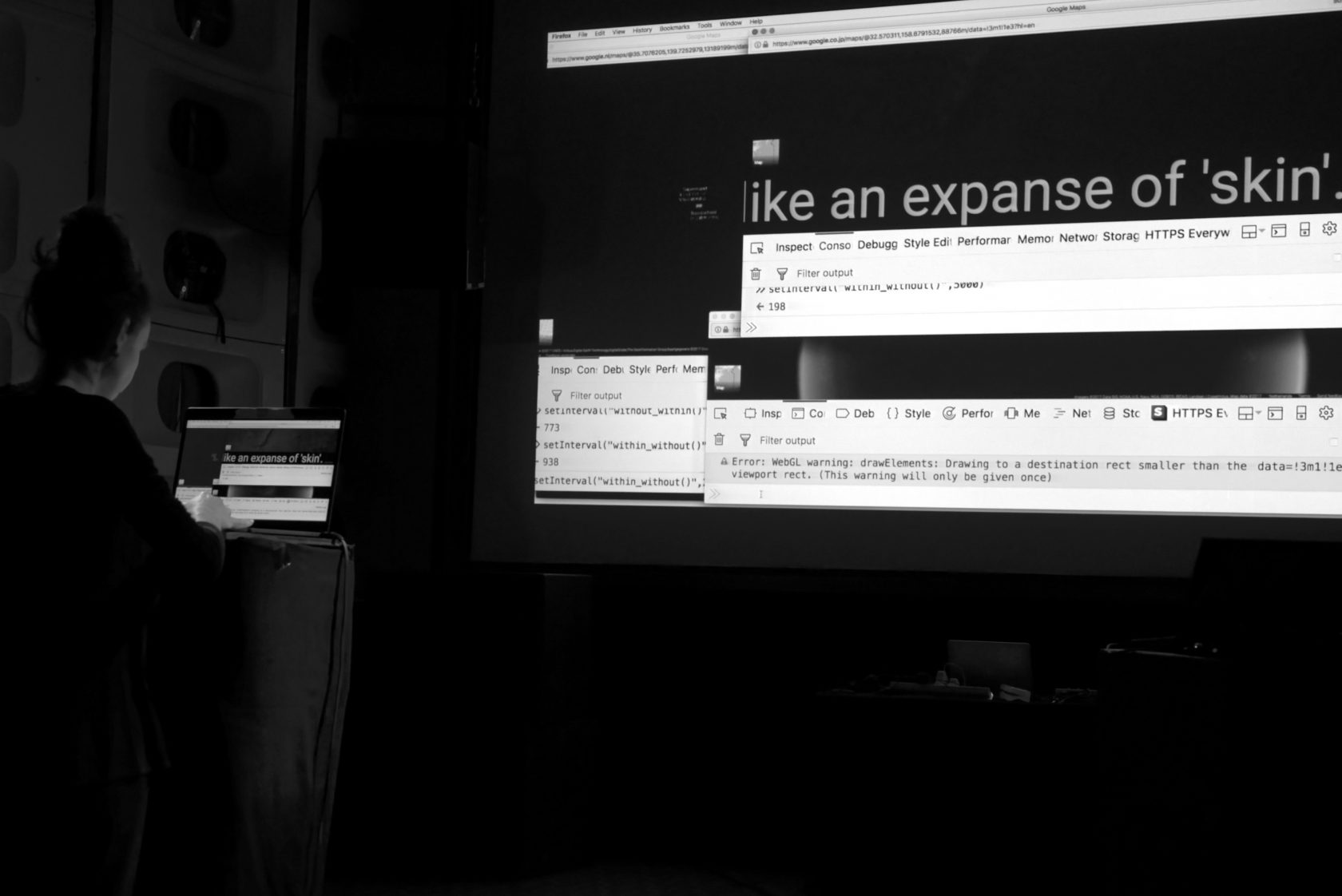

It’s quite different from what I used to do in my dance practice. Some pieces are more structured than others and are split into separate acts. In each act, there is a set of actions that will unfold. There’s also a level of improvisation that is important to have so that every performance is a different one, and so that my interaction with the tools becomes more embodied. I want to be able to respond to something that is happening in the moment and not just follow very strict scores or scripts. I am still learning so I am testing and experimenting. Performing is a way of sharing that moment with an audience.

What do you think about documentation? How do you share?

Performance art practices have always been fighting against documentation. It’s true that the documentation is never what actually happened. It’s never exactly how you experienced it. But if we look at what choreography is and what it does, it’s a tool for writing movement, right? Choreography tries to make dance static. It’s a language that sets movements in stone. So the ways you can interpret choreography can be quite generative. You access a certain form of documentation, which can be a written score, or a video and you can interpret that into different forms and it may never be the same and that’s fine. That’s the freedom and beauty of having documentation as such. I think it really depends on what you want documented. Is it to remember a moment in time? Is it to transfer the knowledge and the information to other people to carry on? For me, it works both ways. It’s an interesting thing on its own that we can work with.

What usually comes first, thinking through your body or thinking through your browser?

It’s more of a feedback loop. There are instances when I start by investigating a new dance style. For example, I went to Argentina for an artist residency and there I was able to learn more about tango, which is something I still dance today. So in that case, I start by embodying these principles and then those become the guiding principles in terms of what I end up coding. I started by thinking about the relationships between bodies in terms of space, movement and timing and how that could create new ways of understanding in an online environment. Sometimes it’s the other way around. It’s really interesting to see how online environments are structured and how we experience them online and how that interferes with our physicality.

Can you share a memorable reaction to your work?

Sometimes when I’m performing and I misspell something and create an error, I can hear the audience gasp, and murmur amongst themselves. It’s interesting to be able to bring this physicality into people who are reading code, which is something that is often so abstract and not particularly emotional. Also because I play with silence, there are moments where every noise the audience makes becomes a part of the performance.

How many times do you perform a single work before you retire it or get sick of it?

I have performed A Web Page in Three Acts many times and it has changed from being three acts to being one act where I focus on one detail. I’ve also changed the themes. For a recent performance in Copenhagen that was curated by Anders Visti, I was focusing on the notion of exhaustion. Many of the tasks I was performing were focusing on that particular theme. For example at V2, I was interested in using the same notion of A Web Page in Three Acts but creating a new system by the end of the performance, which was super long, three or more hours. In the end I would print out my search queries that I use for the performance and I read that in the final half an hour. A Web Page in Three Acts becomes an infinite piece because there are so many ways of approaching it and still making it exciting.

You collaborate frequently. Could you talk me through what that process looks like?

There are collaborations which are quite improvised. This could be because we are at the same event and we join a live jam session and something happens and it’s improvised. I collaborate on longer-term projects as well. I’m currently collaborating with Jonathan Reus, a sound artist and programmer based in The Hague. He has had a very active role in the programming of our project, as well as in the sound material. I focus on the visual aesthetics, and being closer to the world of choreography, in thinking about questions surrounding embodiment and staging and how we can rethink our notions of performing with algorithms. We often help each other in thinking through different ways of doing things.

How does mobility affect your work?

As a performer, I am expected to travel to be at different events or institutions. It’s interesting because now due to the crisis we find ourselves in, all these constraints are put upon us. We also see that most institutions are adapting and moving online. With some of my work, which is heavy in movement or choreography, that becomes a challenge. I’ve been starting to think about how that physical presence of the movement in the performance has been removed and what to do about it. In a few cases it was the binding element of the entire performance so it brings new challenges to think about the fact that I’m not present anymore. I’m not surrounded by the audience. It’s a completely different relationship. On one hand, I do miss the presence of the other and sharing that. But I’m glad that there have been so many tools developed for sharing our creative practices and the ideas surrounding them. It’s good to understand we can carry on using them, developing them further or even creating new ones.

I am more exposed to sound and coding and less exposed to the relationship between the body and coding. Are there people that you look to for inspiration or do you think there was an “ah-ha moment”?

It’s true that there is a strong divide between sound and visual composition. There was certainly a moment where I was introduced to live coding. I was pointed to Alex McLean, who is a very influential person in this world and also initiates a lot of hubs where people come together within the coding community. From there, I was pointed towards Kate Sicchio. She is a dancer that also started using coding to produce her choreographies and to look into the role of language in shaping our movement but through these algorithmic tools. Also Marije Baalman, who is also a member of iii. She also has a really interesting approach to embodiment and has been developing a lot of tools that really think through the role of the body and its presence along with algorithmic compositions. There are also a lot of other people that are very dear to me in the community for other reasons, political stances. Shelly Knotts and Joanne Armitage have been working with feminism and the politics around algorithms which are very important to tackle.

You move between two stereotypically gendering communities, dance and coding. How do you experience your own gender in this hybrid space?

I am very aware of the discrepancy in terms of if you look in certain communities you often understand that they are not gender balanced. It’s not only gender. As in most other practices, we still need to fight for this balance. I do think about my role. I have often been the only female representative on the line up or meet up. There are moments where it’s more obvious than others. It’s important to me to make a priority of diversifying and creating opportunities when I am curating, a way of deciding on the line up. Creating workshops and transferring knowledge is also key for making these tools available so people can participate because you cannot create change without making things accessible to others.

Could you talk a bit more about the accessibility you mentioned?

I think it’s a good principle to put your work out there and make it available. But, it’s not enough for people to understand it. One of the priorities in the work that I do is to understand how to communicate in a way that is already meaningful for those who don’t know the techniques and the language that I’m talking about. This is indeed a lot of extra work on top of what you already do. But I think it’s very valuable because otherwise you’re being more cryptic than open if you don’t make an effort in communicating what you create.

I read that you have some training in Butoh. What did you gain from it for your practice?

It’s a very complex dance genre, both physically and in how you embody the movements. This was part of a residency that I attended a few years ago. I went to Tokyo to learn from different choreographers there. Most of the choreographers didn’t speak English with the fluidity that you or I might be used to. When you go to classes and try to learn something for the first time, you’re used to understanding what people say through the language that you share. There, without knowing Japanese, I had to rely a lot on what I would see and then translating what I would see into my own body. It required a huge investment. Suddenly, the body had to be the focus. We couldn’t rely on language. It was about sharing our muscles’ experiences and sweat. There was a lot of repetition until you would get somewhere where you would potentially get close to what the movement should be performed like. It was super challenging. I simultaneously feel as if I learned a lot and as if I learned nothing.

What does publishing mean to you especially when your practice is such a hybrid?

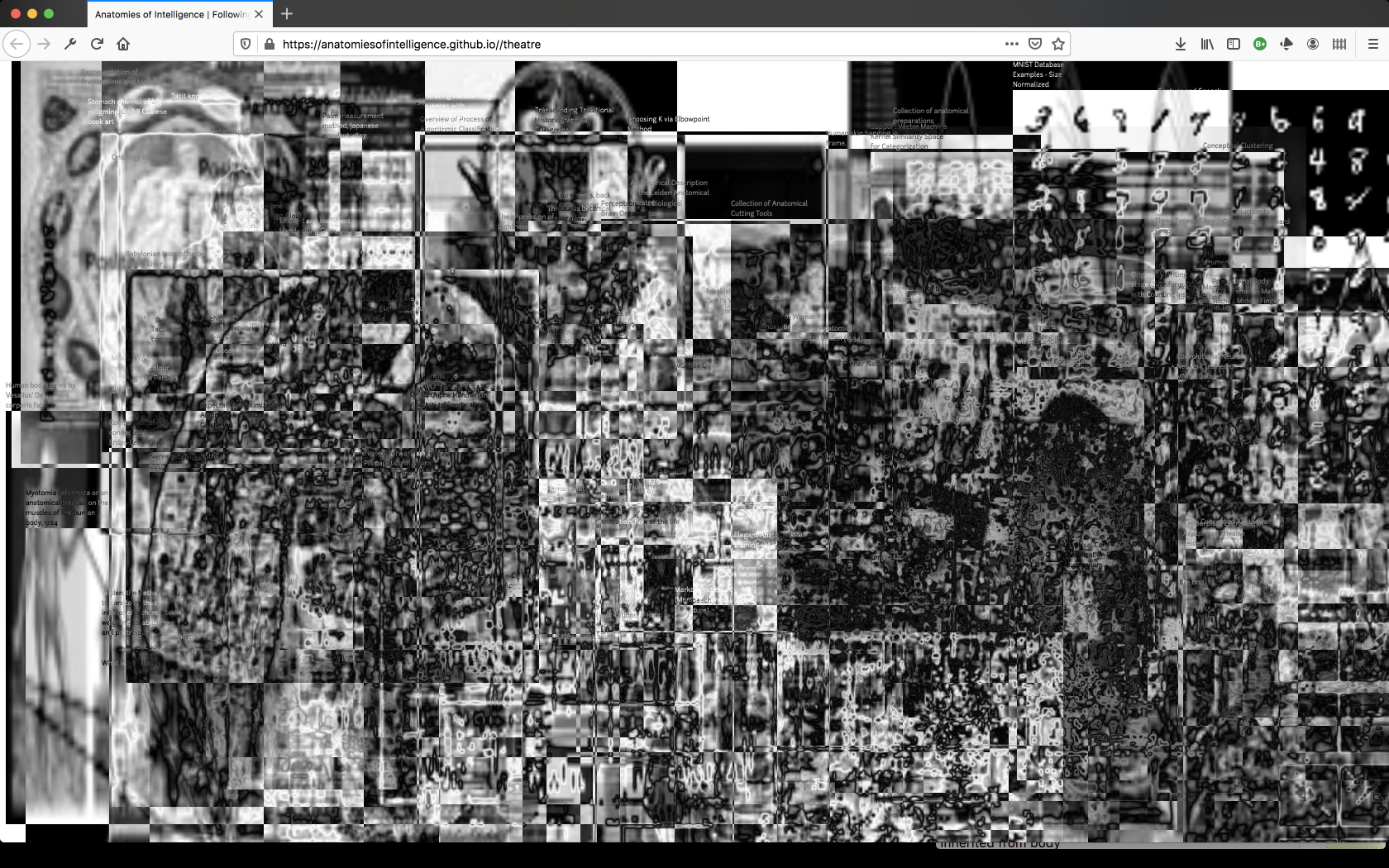

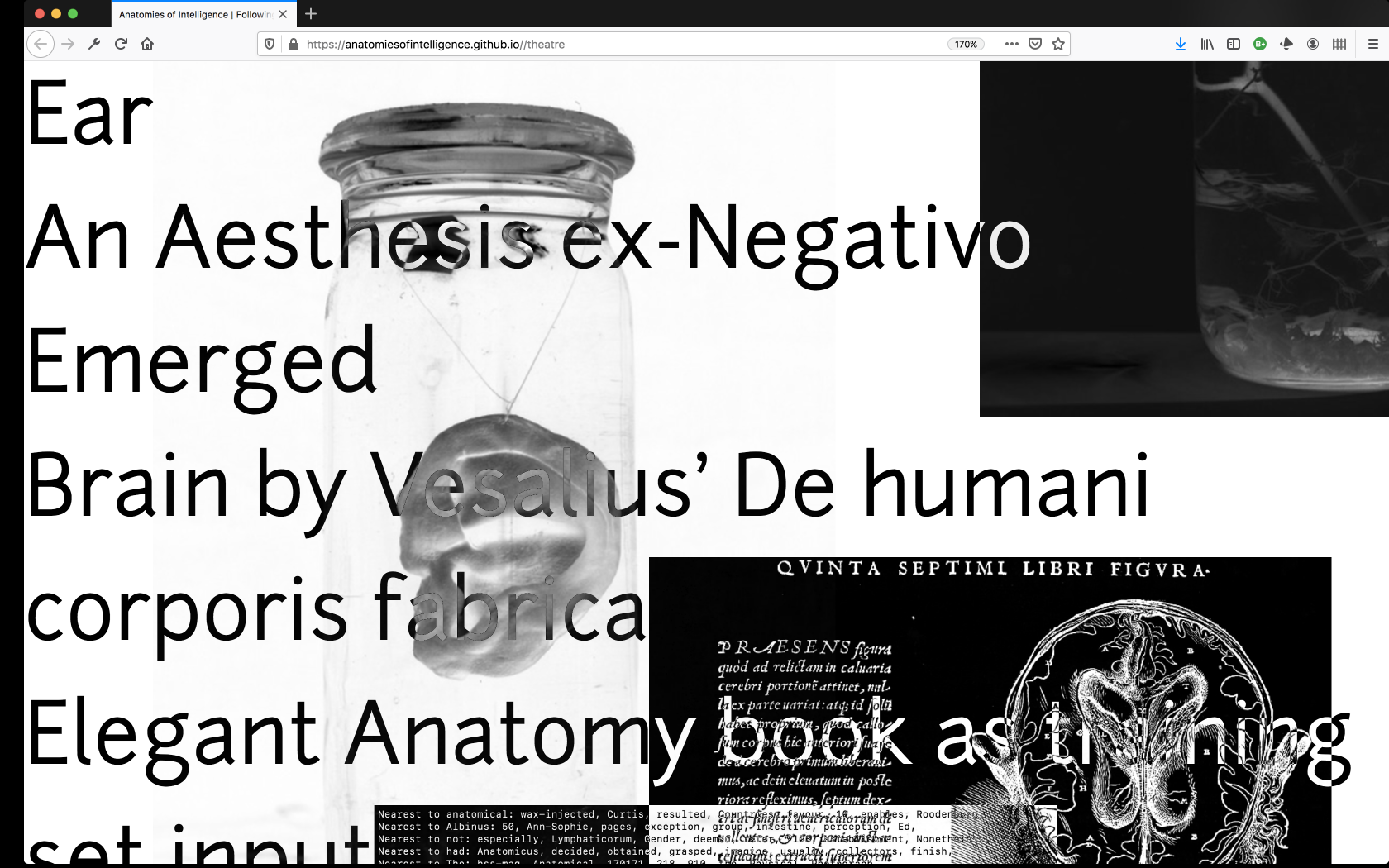

Publishing is a very important concept for me. I connect it with the notion of making your production available so, publishing as in sharing with the public. In the past I printed a small collection of essays where I also have the code printed next to the ideas of each performance. It’s important because this is literary material and you can read code. We can start to weave together different languages and codes and make it more of a shared practice of reading and at the same time less obscure. We are all embedded in so many different algorithms that we might as well take that into our stories. I’m also quite interested in thinking about how the place where you store your algorithms can also be a place of communicating them and giving different viewpoints in how they operate. Actually the project with Jonathan does think of this place of where we perform. Our theatre stage is also a place where our algorithm lives and we bring that to life.

How has the program you’re curating at iii changed with the coronavirus pandemic?

Previously we thought that we would all be at the iii studio and perform live there but now we are going to be online. The audience will also join at a specific time. We still want to make an event out of it so that we have these shared moments with the audience and the performers. Different performers will have different approaches. For example, Naoto Hieda is going to have a live moment where he is going to activate his algorithms and guide us through some movement sequence. The other performer, Angeliki Diakrousi, will provide us with a recording of her performance where she is going to activate a series of voices that have been recorded. The audience is also invited to send their recordings to her. She will share those in that moment. For me and Jonathan, we are still considering what the best approach is. We do rely on networks so we may have to try to find a different format. At the end of the performances, we will meet for a Q+A where Marije Baalman will moderate. She is going to invite us into a conversation where we can speak through the pieces surrounding the event theme, which is called Flesh.

All of the invited artists are interested in the friction between the actual and the virtual, between the role of embodiment and the presence of voice and algorithms in connection and how you can turn these into new perceptual experiences and how you can bring the sensorial into these online environments. I think it’s quite a special group of people to take on this challenge.

You are a co-founder of Netherlands Coding Live. How would you describe this community?

It’s a hub. I wouldn’t say that it’s a collective of people. We are a group of people that all do live coding. We try to invite each other for different performances and things organized in the Netherlands. But what was important to us about coining something “Netherlands Coding Live” was to actually have an address, a URL, an online presence where we could gather each other’s contact information. We also use a chat platform where we talk to each other. If you name something, then it exists, and you can do things with it and people are more excited about participating. We do try to reach out to more people. It’s been a slow but ongoing process, I think, because a lot of it is voluntary. We try to keep a rhythm around the meetups that we do. And then other things come up as great opportunities, like being invited to perform in different places. There is still more work we would like to do. It’s happening slowly, sharing tools and making those tools more visible to others.

Joana Chicau will perform at iii via a livestream on May 24 at 20.00 as part of the event she is curating, NL_CL #2: Flesh. Suggested donation 5-10 euros. Check the iii website for the latest information.

Performances by Naoto Hieda, Joana Chicau & Jonathan Reus, Angeliki Diakrousi.