Meet iii-resident Marianthi Papalexandri-Alexandri

On a rainy October afternoon, I met with sound artist and composer Marianthi Papalexandri-Alexandri, in the project space of iii. Her excitement about her instruments was palpable. For two and a half hours, we talked about everything from her Greek roots to her philosophy on teaching to the visual aspect of sound.

Could you tell me a bit about yourself and your background?

I was born in Greece. I began studying music around the age of 12 but prior to that, I was a rhythmic gymnast for many years. I think this was a very important time. That period helped shape my idea that music is about physical movement, objects, space and sound, all synchronized. I was using space in a critical way, in big, open spaces, which I really like. Then I had an accident and it made me shift to music. I did all the classical training, keyboard, harmony, music theory. At that time I only had a 3 octave keyboard so I think that contributed to my understanding of being unconventional and improvising and staying in the moment. I would practice at home and when I went for a lesson, my teacher had no idea that I only had a 3 octave keyboard. This raised questions of what is a complete instrument and what is part of an instrument for me.

I moved to London to study around the age of 20. There I started improvising with members of AMM, with Eddie Prévost and that was a huge learning experience for me. I was improvising with objects, anything I could find in the room, sometimes with other peoples instruments. Just going and grabbing it, literally. I was starting to explore performing arts, objects, and opening up my own understanding of what my territory was, or could be. From there I went to the University of California, San Diego to do my PhD. In 2008, I both received my PhD and met my partner, Pe Lang. Four years ago, I began teaching at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, where I spend six months of the year. I spend the other six months in Switzerland, where Pe lives.

How does mobility affect your work?

There’s something about entering a new space. I told you earlier about how I was a gymnast. Being a gymnast, you are always stepping into large, empty spaces, dedicated to what you are doing. I think that was valuable in many ways. Changing places means that you are facing your own habits, preferences and standards. For example, I’m used to having my own space, and now I am sharing my space here at iii. I’ve had quite a few residencies. I’m lucky that my work has been supported. I was at Solitude Schloss for a year. I was in Bamberg at Villa Concordia, a residency for artists and composers and writers. There I had my own studio with my own piano. As an artist-in-residence somewhere, you become aware of what you decide to bring with you. When I chose to do my PhD, I made a conscious decision to stay in one place for six months, to see what I could do and have a focused, concentrated period of creating. During that time, I made a piece where everything fit into a box, so I could bring it with me. The instruments that I brought with me here to The Hague follow that same logic. Can I travel with it easily? Can I go through security with it? Does it fit in my luggage? I think that’s a good practice in design, giving myself parameters and constraints. People ask me how I work if I have some things in Ithaca, some in Switzerland. With certain tools, I need double. But it’s a good practice to accept, that the current moment is the situation at hand, and that these are the things in front of me right now. There are other things to discover. You get to step into a completely new landscape of different rules. I love that.

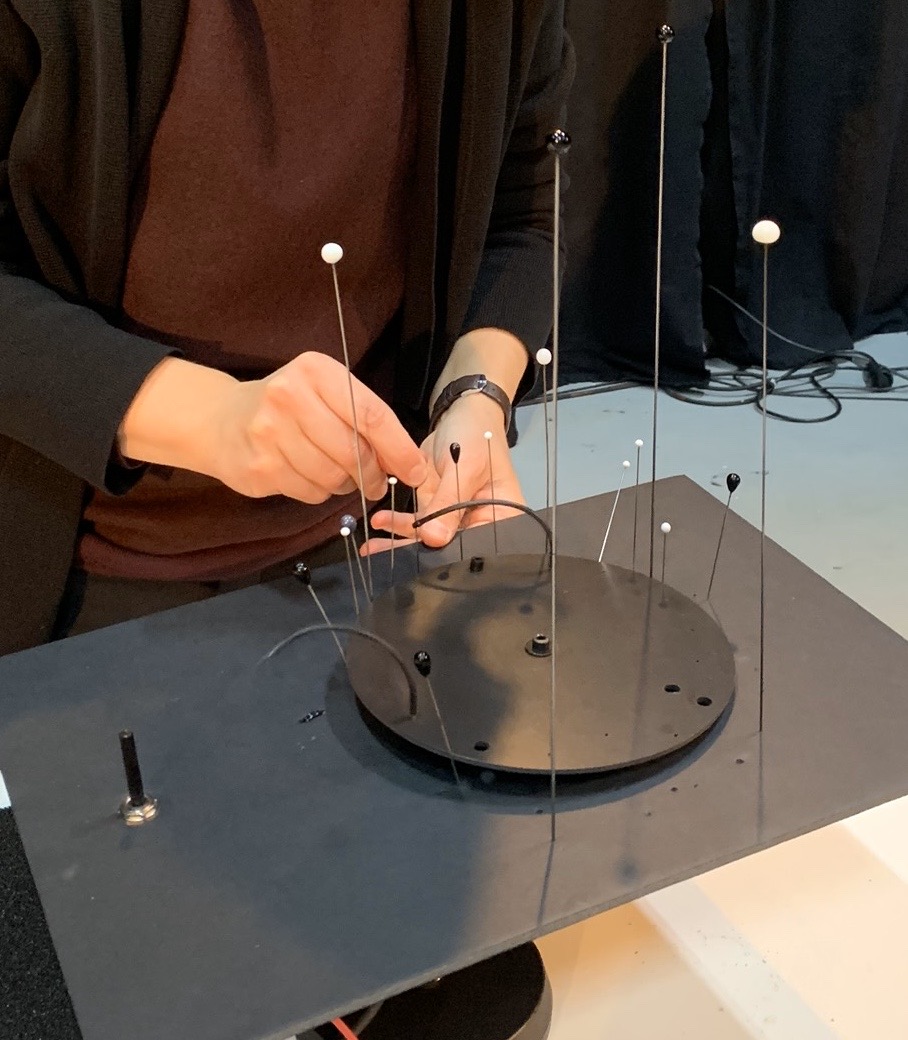

Photo: Anhava

How do you work? What does an average studio day look like?

I don’t have one studio so this is a tricky question. This is referring to a routine and I don’t have such a thing. I try to have chunks of time, or days, when I don’t answer emails so I can focus on working. I like to look at materials and see what the materials are about, and what they want me to do with them. It’s important to go places, to look for physical material, and objects and things I can use. Recently I’ve been having a lot of long conversations with my partner about our understanding of installations and size. For example, how do we perceive large scale? Is it the actual dimensions of the object? Could it be one empty room but just projection? Does that make it large scale? Many conversations.

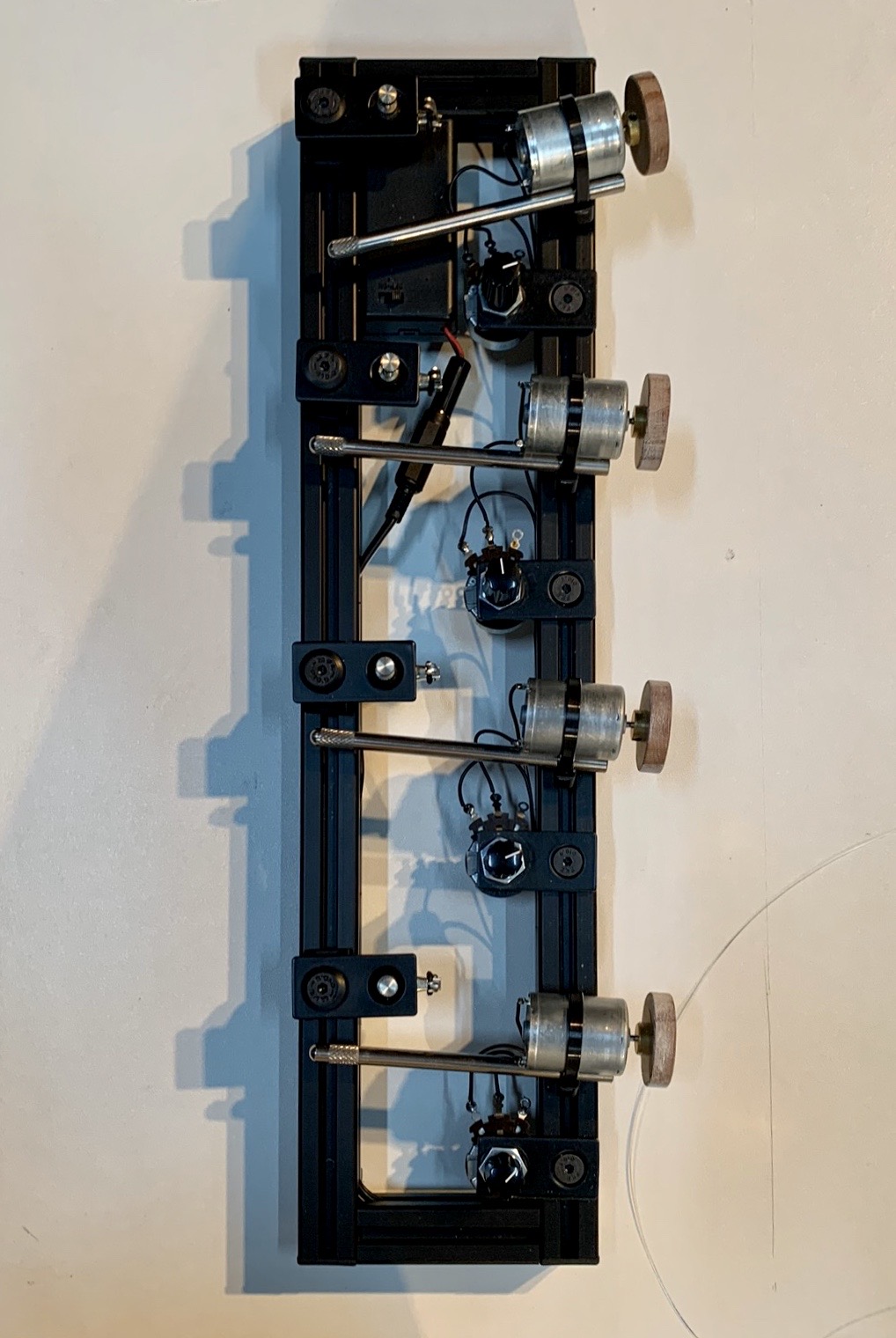

Image: Pe Lang

You collaborate frequently with Pe Lang. Could you talk me through what that looks like?

I contacted Pe after a friend of mine encouraged me to check out his work. When we first met, he was working with motors and collaborating with an artist named Zimoun on a project “Untitled Sound Objects”. It’s quite similar to what I do. That was common ground for us. I got in touch with him to ask him to make something for me that could make a continuous but not repetitive sound. That’s when the dialogue started. He sent the device he made for me. I immediately knew there was something there I couldn’t ignore. We met and we both gave up partners and where we were living and moved to Berlin.

I come from Greece and we are dramatic and we also like our symmetry. You can see that in Ancient Greece. There is importance placed on beauty and proportions but also illusions. The Parthenon, for example. We play. We don’t have a system. Nothing works. So, you have to come up with your own solutions. You have to be creative there. I mean, really, really creative. Pe is from Switzerland, where everything is organized and works very well. They have a good sense of quality and precision. I think this mixture is very interesting. I’m somebody who is always asking about the friction that gives energy to the artwork. If everything is working so well, then what makes it an artwork and not a design object? We have a lot of discussions about art, design, and decoration. Pe loves the “why?”.

We often place a lot of importance on career, that you have to be careful with your job, but I think you have to be careful with your partner. You have to be careful who you choose to be around, and your friends. This is very important to me. The choice of who you surround yourself with. Professions you can always change. It’s not one choice you make when you’re 18.

Your installations Sound Sculpture I, II, III and modular | nº 2 are visually very elegant. How much importance is placed on the visual aspect of your work?

I try to be a bit relaxed in terms of presentation but I rarely succeed. Sometimes I say to my students, “if you can’t make it sound good, just try to make it look good.” With sound, there is always so little time to be in the venue, to soundcheck, to rehearse. For me, part of my practice in sound is also to create something visual. That’s something I can have control of, to some extent. I can have a contribution. A lot of importance is placed on the visual aspect. If you work with neutral colors, they are more open to interpretation but they don’t give you too much information. I find this refreshing and it helps me relax somehow. You can highlight the movement visually.

When performing an instrument, how do you decide when the piece is finished?

It’s a good question. Because how do we know when we compose which sounds should be a certain length, and when should we move to the next one and when are we satisfied. A lot of times, distractions are very important. For example, it’s not that you keep the successful sounds for too long. There’s also some techniques you can use. Let’s say I want to put a bright light directly in your face. If I remove that light, what happens? It creates an impact. It provokes you in some way. It’s a balancing act.

And you can’t go on too long. It’s like, you can’t have too many sweets, otherwise you’ll get a stomachache. It’s great when I’m told 10 minutes or 15 minutes because it can be endless. What I feel I’m doing is programming with materials and its behavior depends on how I arrange the elements of the instrument. I can generate so many different patterns.

Can you see this functioning also a sculpture?

Yeah, totally. I actually think of it more as a sculpture that I play with, activate.

Do you procrastinate and if so, how?

I love being on my terrace in Switzerland and watching the clouds. I think nature is so amazing. I never expected I would say this because I love cities but since living in Ithaca and Switzerland, but I’ve come to realize how much satisfaction I get in watching the sky. But the best things come for free in life. I know this has been said so many times. So what? It’s true. There is something about nature that never fails. It always gives you something. I think it’s absolutely necessary. I go for walks with my students. There have been times when I enter the classroom and I tell them “I don’t know what to do today but I have a feeling that we should go out for a walk.” There is always something for us to discover. I want to have more time to reflect and rest, because you need to rest your mind. A plant doesn’t need water all the time. You will kill it if you overwater it. You need to understand the conditions. This is really important.

What does the compositional process look like in your case? Do you always work with scores, even in an abstract sense?

I used to be so precious with my scores. I actually used to make drawings of how my hands move. Many years ago, my father said to me “I don’t know if you’re going to become a very good composer but your drawings are really good”. I went from rather simple scores with certain annotations, sort of upside down, doing things. For example with the guitar, doing the reverse. From there I moved to scores that were literal drawings of the action, not the result (the sound). Now if you see my scores, they are more like manuals. How to set up. How to control. I take pictures and I make videos. I have some symbols which show the structure and the timeline. For many years now, I work only in time, seconds and minutes, because that’s how our life is structured. So, the score for me is the same as if you’re going to send your manual to a museum and you can’t be there so the technician can read it and set it up, and read some information about how to approach the instrument or composition. I have to say that in general, the role of the score for me as a composer has changed.

Do you usually work with trained musicians/performers?

I usually do but not exclusively. I’m teaching a course at Cornell right now called “Shaping Sound” and I can tell you when you have enough time with people, you can train them and tune them. Some people have this sensitivity and others don’t. It doesn’t mean that if I have the chance to work with a classically trained performer it’s the best match, necessarily. My students, who have no musical background, have succeeded in performing and creating things that are really great. You’ll always have a good result as long as there’s enough time to invest and as long as both sides are open and have a forward thinking approach. And then it’s a lot of things to think about, ergonomically. There’s a lot to do with the body. I sometimes build things that are made for a specific person. Now that I think of it, I worked on one artwork with a chess master. That was a beautiful collaboration. She’s not a trained musician but there was something I really liked about the way she moves her body. So the answer is yes and no. It varies. Even a classically trained musician, when you deal with a new instrument like this, they are no longer trained. There’s a learning curve, on both sides.

Is it important for you to rehearse with performers? And if yes, what would a rehearsal look like?

I like to think of it more as a workshop than a rehearsal. I like to have them over to my studio. It’s important to see where the work is coming from and who made it and how it was made. I start by giving them materials to hold, telling them where it comes from, and then I demonstrate. Before that, I give them some videos and something to listen to. It’s more about tuning them, warming them up. I don’t necessarily create a structure. I just see what happens and I shape it, and shape it and shape it. Ergonomically it needs to make sense as well. I think it’s more about bringing these elements and forces and people together and you reshape them collectively. I am demanding, though. I am demanding in terms of the engagement, in the dedication that you show and in learning how to oscillate between the performing, operating, and listening. I have to say that for me, it’s not so easy to be satisfied. It’s not that I’m not satisfied with the person. It’s more the frustration that we don’t have enough time to actually build this connection and to help them build this connection. The more time I have, the better.

Can you share a memorable reaction to your work?

I don’t have one, specific memorable reaction but it’s always interesting when people say that they feel welcomed by the work. Or that it reminds them of nature. I’ve heard it sounds like frogs, or somebody snoring, or listening to lungs with a stethoscope. If I have a concert situation, the audience usually runs to the stage at the end because they want to see. It’s always a little bit of a mystery, even when I explain how it works.

Marianthi Papalexandri-Alexandri will perform at No Patent Pending #38 on October 12, 2019 at iii workspace, Willem Dreespark 312 in The Hague

Doors open 20:00 / Event starts 20:30 / Tickets: €5-€10 sliding scale

Performances by Mario de Vega, Marianthi Papalexandri-Alexandri, Budhaditya Chattopadhyay and Mischa Daams.