Stroom Invest interviews / curator #8 Maziar Afrassiabi

Maziar Afrassiabi is a curator whose work seeks to establish new connections between artists and non-artists of different backgrounds and traditions in order to imagine new post-institutional and peer-to-peer organisational models of production and presentation of art. Ultimately the goal is to automate art production. He is the founder and director of Rib art space in Rotterdam as well as an adviser for Sculpture International Rotterdam and a member of the board for Platform Beeldende Kunst.

Starting at the beginning, where are you from originally?

I am born in Tehran, and when I was two we moved to Isfahan. That was in 1975 when the war in Vietnam came to an end and four years before the Iranian revolution erupted. The year Oum Kalsoum died aged 77, and the failed attempt by Dutch Moluccans to kidnap queen Juliana. The year Microsoft was founded by Bill Gates.

Where and what did you study?

I studied art at HKU in Utrecht. I graduated in sculpture with live poultry and complemented it with what I then thought was a conceptual art take on video and performance art and inserted a bit of live writing as institutional critique during the openings of the graduation show. I thought I would win the prize with my smart moves. But I was young and naive, and the award went to a formalist student. Ironically this was in the mid-‘90s. Also way before discussions on anthropocentrism in philosophy and art became popular and the importance of the relation between human and animal entered art discourse.

One of my main teachers didn’t know who Josef Kosuth is, and I needed to ask his opinion about him, because I had just discovered him and needed some feedback. I had also just heard of the internet and wikipedia didn’t exist yet. Another teacher insisted that I make art that was founded on my cultural background. On my so-called origins. They had both permanent contracts and are now with pension.

Live poultry sculpture? Tell me more about that.

I used live poultry, live chickens and roosters. That was part of my graduation piece. Our studios where in a long corridor. They were just walking in the studios, behind the assessing tutors. And on top of other student’s works – shitting, making new sculptures always too late to be assessed as my work – and they were in the garden.

And what happened also was they stayed after I graduated both in life and in art. Years later I heard someone graduated with chicken paintings. But also they affected the surrounding urban infrastructure: the chicken exploded in numbers, so the municipality had to put up street signs – Chickens Crossing, be careful and stuff like that after allegedly some accidents. Also I heard that once during the bird flu they were cleared. But they are still there. I think this work was perhaps the germ of a certain automated form of curating.

Do you consider yourself an artist as well as a curator?

I think every artist or curator possesses different degrees of artistic, organisational or even pedagogical intelligence and skills. I know of artists that are so meticulously organised, that I wished they could assist a curator who, on an artistic level, is much more interesting than the artist in question and vice versa. Beyond that, I am not so much occupied with institutional titles. I measure someone’s qualities based on the degree in which they can or are willing to be anarchic towards and deviate from their own comfort zones, from the pressure to deliver, finding identity in perpetual alienation rather than commodification. Futurists that can take others on board of adventurous journeys.

For me as someone who grew into the production format of curating partly by accident and remained in it as an artistic choice and not by education or career, and as someone that used to literally make art and is able to build with his own hands and not self-evidently by someone else’s or by instruction, it is meaningless and unclear what the purpose of such division would be. Except that there are distinct funding guidelines for curators and artists. Social contracts do not necessarily reflect realities and are meaningless when the curtain falls.

Some of the artists or curators I work with always joke that they don’t know of any curator that can build a show, do art handling, curate, write texts, make an occasional art work, produce and perform music, teach and clean the toilet (and still not be paid). I find this a tragicomic compliment.

What living artist do you most admire?

Naturally, the artists I admire are those I work with. Each has its own place, and each is a composite bibliographic body of art historical references anyway (some might even have 7 percent Picasso in them), meaning one can trace back a particular (art) historical genealogy in every artist. The notion of admiration and having idols only made sense to me when I was in the early years of art school. Even then I only admired a teacher. His name was Jan Zeven, who had created his own eclectic curriculum and organised educational and adventurous bus trips around Europe. His teachings were based on what he called art-geography and were very inspiring and formative for me.

Currently I am developing a few long-term projects with artists Paul Elliman and Brud (a collective from India and Poland led by Aditya Mandayam) accompanied by about 12 other artist, representing a diverse set of practices, generations and geographies. It’s a collective “peer-to-peer” post–art-scene approach to production. And I continue working with the artists I previously worked with. These are artists with serious commitment to their work and research, and I simply am honoured to work with them and become a shareholder of their journeys. It doesn’t matter what age they are. It’s almost about the spirit of the person and his or her alleged place in the world, in history and their futuristic gaze.

Can you talk about the idea of “applied fiction”?

The term, as far as I know, comes from pedagogical contexts, where fiction (metaphor, stories) is used to enhance remembering in children during learning. The term came up in a conversation recently about the reenactment of narrative works, both from history writing and literary sources, and how to make them part of the specific reality of a particular local context, without resorting to the usual representational modus of art, where references are presented as aesthetic quotes in the exhibition context. In short, how can fiction become part of and feed back into the life of a certain social infrastructure?

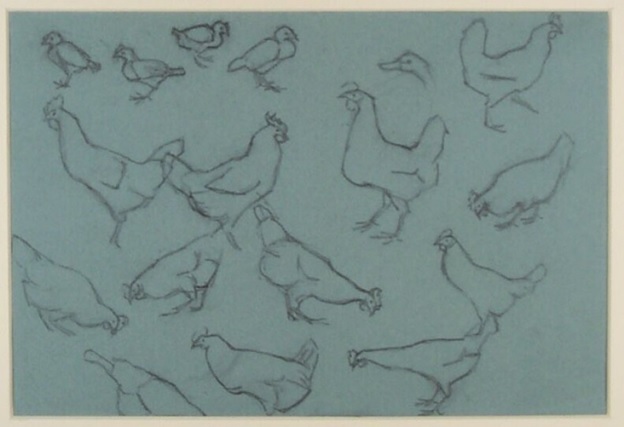

In one of the exhibitions I did, there was a work (see images below) included that was commissioned by Rib, that applied fiction to create a real record of a cohabitation of a series of mostly disconnected artists, practices and generations in Rotterdam on the same plane. The basis of the work was a drawing from the print collection of the museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam. A small pencil study of chickens from early last century, by artist Julie de Graag. There were approximately 16 chicks and chickens

I wanted to show it in Rib as part of an exhibition, but because we don’t have climate control it proved impossible. I decided to seize this so-called unforeseen practical constraint as an artistic opportunity. Interestingly, both the drawing itself (creating a fictive space of 17 chickens together), as well as its museological condition were extended in its future life as a drawing and as a fictive representation of a local art scene.

Rather than reproducing the original, it therefore became a question of how to transfer and, in the process even, transform the artistic and political potentialities of one drawing into another and in the process implicate a certain social context, beginning and ending with the medium of drawing, with the individual depicting a collective (chickens) and ending with a collective depicting individual chickens (each having their own artistic signature).

So in the end, I asked 11 Rotterdam-based artists from different generations and different levels of fame to each reproduce one of the chickens. Our ‘volunteer’ would bring the drawing around to artists’ studios on a bike, they would choose a chicken from what was left, reproduce it with pencil, and then we would bring it to the next one. Also, as we moved forward, the options were reduced. And duo artists didn’t tell us which one of the two made the drawing.

So to make the story short, this work is an example of applied fiction. Its fiction but it’s a realised fiction. There are currently six chicken slots open in the drawing. Hopefully Boijmans would like to include it in their collection at some point.

What is your motto or personal philosophy as a curator?

Without being necessarily a so-called Deleuzian (neither apologetic for seeming to be one), at this moment I feel this quote from Gilles Deleuze sums it up well. It is a quote that refers to collaboration and authorship:

“The key thing is how to get taken up in the motion of a big wave, a column of rising air, to ‘get into something’ instead of being the origin of an effort”.

The quote taken in isolation says nothing and everything. So let me clarify it in the context of curating. As far as I know, I believe there are two prevailing forms of curating in the Netherlands at the moment.

The first one I would call representational curating. The second facilitative curating.

In the latter version, one is merely doing it for the sake of facilitating artists or talents based on a consensus of quality, prescribed relevance and aesthetics, all of which presumes an origin, in this case laid out in criteria documents or popularized by the taste of the editorial teams of art magazines or juries. This form of curating doesn’t require a curator at all, but a politician, a manager, a civil servant, a marketeer or an entrepreneur.

I was talking recently to a friend artist and he was saying that the prevailing curatorial model in art today is recycling what colleague curators recycle, a kind of a lazy ecology of inter-professional endorsement.

The second prevailing model, and related to the first one, is representational curating, where curating becomes a form of performative, safe risk-taking. Often this is related to careerist dynamics in the art world. In my view, there is a persistent epidemy in the art world of inconsequent curatorial claims. It is as if on the one hand you are required to be political and on the other you have to present it in a depoliticised way in order to be able to have a nice opening and to keep your job. But more importantly, my critique concerns the fact that this type of curating is a result of a logical flaw.

To give a simplified example: A curator or artist wants to address homelessness. He or she decides to turn the art space/museum into a temporary shelter for the homeless or even build tents for them in the suburbs. The motive for this is probably to create real social change with art and to make a political statement.

In my view, the very political potential of homelessness is countered and neutralised with this action, namely by approaching it as a problem to be managed. My position here would be, rather than giving temporary homes to the homeless, and present it as a political artistic gesture, one could explore ways to adopt homelessness as a praxis. In Deleuzian terms, to become homeless. Can one have a house, a job and a partner and still live a homeless life? I would encourage though helping the homeless and removing the causes of homelessness, but I don’t see why art should be the best instrument to this end, while we have great activist and NGO groups who can do it better. To me art is a tool of imagining.

Hence, for me, art in general and curating as a subgenre of art should be always centred around the ‘what if’ and not so much the ‘as if’. It should be stated as a ‘real’ proposition. Even the whole infrastructure and organisation one is running should function as a proposition and not as a habitual container of a series of costly inconsequentialities.

For me, curatorial work is mostly about nurturing, refining, connecting and expanding a network of practices and ideas, present, past and future, based on certain commonalities, even if contradictory. In this liquid scheme, the public is a fiction. It simply doesn’t exist. I find it very helpful to think of the public as an impotent fabrication of politicians and entrepreneurs. To abandon the representational trope in curating is to abandon the public and declare it dead.

I tend to increasingly think and act in terms of materialisation of networks and peer-to-peer (Brud’s term) work. It’s all about doing things with others that were previously unimaginable. The public is a disrespectful construction. It assumes a ‘we’ who has something to offer to a people who have nothing to offer to us. The public is there to be served and it is sovereign in its capacity to offer us nothing in return for our services, other than financing the continuity of the same relation. The very same public can also, by its whims, render us invisible.

I haven’t been to the current Berlin biennale yet. However, I feel from stories I hear, and so far reading the first paragraph’s of Mohammad Saley’s article on it, that the chief curator and her team managed something similar. To go beyond the representational. Only potential issue I see is that perhaps, out of necessity, the very core of the curatorial vision here is itself commodified, frozen into a consumable representation of a case study of a desire to do things differently. The question is of course if this is unavoidable in such a context. I hope I can see it soon. But it sounds really inspiring.

Anyway, I believe we can abandon the model of a zoo even in a museum context, where the basis of encounter is displacement, dislocation, objectification, showcasing, categorisation even and when it concerns contemporary art. In that sense, perhaps not much has changed structurally.

What do you mean that the public is a construction?

I don’t have problems with people going to museums. It’s more that from a curatorial point of view, the looming public demand in the curator’s head contaminates the purity and clarity of her or his vision. The public for art is basically increasingly the judge of what is good art and peer pressure could equally be a problem and fall under the rubric of public. That is exactly how commercial TV works. If you give in to it, you are lost, and your practice becomes an acrobatic and aestheticised answer to political pressures on art. The public should not decide on the artistic process but be either co-producer or an after-the-fact viewer. The notion of serving and service is somewhat impotent.

So it’s more about what type of relation do you engage in. What type of productive relation do you have with each other? On the basis of that relation, I would like to define the public, And perpetually redefine my own role aswell. When we think about it in these terms, one realizes that it’s completely redundant then, the term public.

Do you mean that art should be more participatory on the part of the public?

Even participation has a bitter connotation in our society because it’s a very neoliberal term. It’s based on the fact that the state has no responsibility and you have to yourself participate and survive basically, in order to reduce the government’s spending.

What I am saying is that the public is a political fiction.

I get the sense that you’re resistant to labels or being defined by where you come from or where you’ve been. Why is that?

When you are coming from outside a place you notice the natives or autochthones are never addressed in terms of their ethnic background, as if they don’t have ethnicity at all. There’s a Rotterdam sociologist Willem Schinkel who talks about this in the context of Dutch integration policies. This lack of ethnicity of course assumes a position of power and privilege. It is as if the first entry point for someone is always this idea of being an outsider or being not from here – that’s why I have a problem with that.

Naturally it’s got nothing to do with being proud with one’s background, it has to do more with the fact that rather than entering the relation with a clean sheet and allowing the other to introduce him or herself on their own terms, from the outset the frame is imposed, and this will consequently affect everything that comes after that.

Also people sometimes tend to connect automatically one’s practice with one’s background. I would like to enter a relation in an open field.

A few years ago, you founded Rib in Rotterdam. Can you tell me a bit about how that came about?

Rib started from a desire to create a support-structure for a dispersed form of practice based on an evolving and growing network of friends and colleagues to nurture and further develop these relations in a concentrated and efficient manner based in and around a physical address. Relations that are formed on the basis of a shared understanding of how to act and behave in the world and in one’s immediate surrounding.

Besides Rib, what other projects do you have in the works?

Currently I’m working on the realisation of a permanent public art work in Rotterdam, which consists of removing the colour yellow from the white light spectrum. Also as part of the advisory commission of Sculpture International in Rotterdam, we are exploring fitting approaches concerning art’s role in the context of South of Rotterdam. Also I am a relatively new member of the board of Platform BK, which means identifying and making public issues relevant to the field, issues mostly of both a practical and ideological nature.

What are you looking forward to, or what do you hope to achieve during your Stroom Invest Week residency?

First of, I am honoured to be asked to be part of this years Stroom Invest Week. I hope I can contribute in a meaningful way. And I hope to be surprised and meet nice people.

—————————————–

In a collaboration between Jegens & Tevens and Stroom Den Haag a series of interviews will be published with (inter)national curators, artists and critics participating in Stroom’s Invest Week 2018.

The Invest Week is an annual 4-day program for artists who were granted the PRO Invest subsidy. This subsidy supports young artists based in The Hague in the development of their artistic practice and is aimed to keep artists and graduates of the art academy in the city of The Hague. In order to give the artists an extra incentive, Stroom organizes this week that consists of a public evening of talks, a program of studio visits, presentations and a number of informal meetings. The intent is to broaden the visibility of artists from The Hague through future exhibitions, presentations and exchange programs. The Invest Week 2018 will take place from 18 to 22 June, the public evening is on Wednesday following the exhibition My Practice My Politics.